Shemini, Sh’mini, or Shmini (שמיני — Hebrew for "eighth,” the third word, and the first distinctive word, in the parshah) is the 26th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the third in the book of Leviticus. It constitutes Leviticus 9:1–11:47. Jews in the Diaspora read it the 25th or 26th Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in late March or April.

The parshah tells of the consecration of the Tabernacle, the death of Nadab and Abihu, and the dietary laws of kashrut.

The Two Priests Are Destroyed (watercolor by James Tissot)

Summary

God Consecrated the Tabernacle

On the eighth day of the ceremony to ordain the priests and consecrate the Tabernacle, Moses instructed Aaron to assemble calves, rams, a goat, a lamb, an ox, and a meal offering as sacrifices (called korbanot in Hebrew) to God, saying: “Today the Lord will appear to you." (Leviticus 9:1–4.) They brought the korbanot to the front of the Tent of Meeting, and the Israelites assembled there. (Leviticus 9:5.) Aaron offered the korbanot as Moses had commanded. (Leviticus 9:8–21.) Aaron lifted his hands toward the people and blessed them. (Leviticus 9:22.) Moses and Aaron then went inside the Tent of Meeting, and when they came out, they blessed the people again. (Leviticus 9:23.) Then the Presence of the Lord appeared to all the people and fire came forth and consumed the korbanot on the altar. (Leviticus 9:23–24.) And the people shouted and fell on their faces. (Leviticus 9:24.)

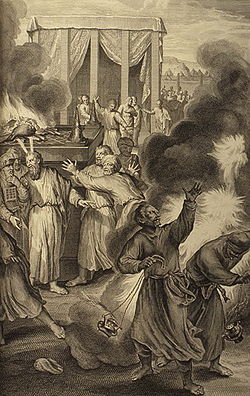

Aaron's Sons, Nadab and Abihu, Destroyed by Fire (engraving by Matthäus Merian)

Nadab and Abihu

Acting on their own, Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu each took his fire pan, laid incense on it, and offered alien fire, which God had not commanded. (Leviticus 10:1.) And God sent fire to consume them, and they died. (Leviticus 10:2.) Moses told Aaron, "This is what the Lord meant when He said: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, and gain glory before all the people,’" and Aaron remained silent. (Leviticus 10:3.) Moses called Aaron’s cousins Mishael and Elzaphan to carry away Nadab’s and Abihu’s bodies to a place outside the camp. (Leviticus 10:4.) Moses instructed Aaron and his sons Eleazar and Ithamar not to mourn Nadab and Abihu and not to go outside the Tent of Meeting. (Leviticus 10:6–7.)

And God told Aaron that he and his sons must not drink wine or other intoxicants when they entered the Tent of Meeting, so as to distinguish between the sacred and the profane. (Leviticus 10:8–11.)

Moses directed Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar to eat the remaining meal offering beside the altar, designating it most holy and the priests’ due. (Leviticus 10:12–13.) And Moses told them that their families could eat the breast of the elevation offering and the thigh of the gift offering in any clean place. (Leviticus 10:14.)

Then Moses inquired about the goat of sin offering, and was angry with Eleazar and Ithamar when he learned that it had already been burned and not eaten in the sacred area. (Leviticus 10:16–18.) Aaron answered Moses: "See, this day they brought their sin offering and their burnt offering before the Lord, and such things have befallen me! Had I eaten sin offering today, would the Lord have approved?" (Leviticus 10:19.) And when Moses heard this, he approved. (Leviticus 10:20.)

Dietary Laws

God then instructed Moses and Aaron in the dietary laws of kashrut (Leviticus 11), saying: “You shall be holy, for I am holy.” (Leviticus 11:45.)

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

Leviticus chapter 10

Philo interpreted Leviticus 10 to teach that because Nadab and Abihu fearlessly and fervently proceeded rapidly to the altar, an imperishable light dissolved them into ethereal beams like a whole burnt-offering and took them up to heaven. (On Dreams 2:9:67.)

In classical rabbinic interpretation

Leviticus chapter 9

Rabbi Helbo taught that after ministered in the office of High Priest for the seven days of consecration, Moses imagined that the office was his, but on the seventh day (as indicated by Leviticus 9:1) God told Moses that the office belonged not to Moses but to his brother Aaron. (Leviticus Rabbah 11:6.)

Rabbi Tanhum taught in the name of Rabbi Judan that the words “for today the Lord appears to you” in Leviticus 9:4 indicated that God’s presence, the Shekhinah, did not come to abide in the Tabernacle all the seven days of consecration when Moses ministered in the office of High Priest, but the Shekhinah appeared when Aaron put on the High Priest's robes. (Leviticus Rabbah 11:6.)

Nadab and Abihu consumed by fire from the Lord (illustration from 1728 "Figures de la Bible")

Leviticus chapter 10

According to the Sifra, Nadab and Abihu took their offering in Leviticus 10:1 in joy, for when they saw the new fire come from God, they went to add one act of love to another act of life. (Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:4.)

Abba Jose ben Dosetai taught that that Nadab and Abihu died in Leviticus 10:2 when two streams of fire came forth from the Holy of Holies and divided into four streams, of which two flowed into the nose of one and two into the nose of the other, so that their breath was burned up, but their garments remained untouched (as implied in Leviticus 10:5). (Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:7.)

Bar Kappara said in the name of Rabbi Jeremiah ben Eleazar that Nadab and Abihu died (as reported in Leviticus 10:2) because of four things: (1) for drawing too near to the holy place, (2) for offering a sacrifice that they had not been commanded to offer, (3) for the strange fire that they brought in from the kitchen, and (4) for not having taken counsel from each other, as Leviticus 10:1 says “Each of them his censer,” implying that each acted on his own initiative. (Leviticus Rabbah 20:8.)

Rabbi Eliezer (or some say Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob) taught that Nadab and Abihu died only because they gave a legal decision in the presence of their Master Moses. Even though Leviticus 9:24 reports that “fire came forth from before the Lord and consumed the burnt-offering and the fat on the altar,” Nadab and Abihu deduced from the command of Leviticus 1:7 that “the sons of Aaron the priest shall put fire upon the altar” that the priests still had a religious duty to bring some ordinary fire to the altar, as well. (Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 63a; see also Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:6.)

Rabbi Simeon taught that Nadab and Abihu died only because they entered the Tent of Meeting drunk with wine. Rabbi Phinehas in the name of Rabbi Levi compared this conclusion to the case of a king who had a faithful attendant. When the king found the attendant standing at tavern entrances, the king beheaded the attendant and appointed another in his place. The king did not say why he killed the first attendant, except that he told the second attendant not to enter the doorway of taverns, and thus the king indicated that he put the first attendant to death for such a reason. And thus God’s command to Aaron in Leviticus 10:9 to “drink no wine nor strong drink” indicates that Nadab and Abihu died precisely because of wine. (Leviticus Rabbah 12:1.)

According to the Sifra, some say that Nadab and Abihu died because earlier, when at Sinai they were walking behind Moses and Aaron, they remarked to each other how in a little while, the two old men would die, and they would head the congregation. And God said that we would see who would bury whom. (Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:3:4.)

The Sin of Nadab and Abihu (illustration from a 1907 Bible card)

In Leviticus 10:3, Moses told Aaron, “This is what the Lord meant when He said: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, and gain glory before all the people.’" A midrash taught that God told this to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, when in Exodus 29:43 God said, “there I will meet with the children of Israel; and the Tabernacle shall be sanctified by My glory.” And Moses said to Aaron, “At the time that God told me, I thought that either you or I would be stricken, but now I know that they [Nadab and Abihu] are greater than you or me.” (Midrash Tanhuma Shemini 1.)

Similarly, the Sifra taught that Moses sought to comfort Aaron, telling him that at Sinai, God told him that God would sanctify God’s house through a great man. Moses had supposed that it would be either through Aaron or himself that the house would be sanctified. But Moses said that it turned out that Aaron’s sons were greater and Moses and Aaron, for through them had the house been sanctified. (Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:3:6; see also 99:5:9.)

Rabbi Akiba taught that because Aaron’s cousins Mishael and Elzaphan attended to the remains of Nadab and Abihu (as reported in Leviticus 10:4–5), they became the “certain men” who Numbers 9:6 reported “were unclean by the dead body of a man, so that they could not keep the Passover.” But Rabbi Isaac replied that Mishael and Elzaphan could have cleansed themselves before the Passover. (Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 25a–b.)

A midrash taught that when in Leviticus 10:16 “Moses diligently inquired [literally: inquiring, he inquired] for the goat of the sin-offering,” the language indicates that Moses made two inquiries: (1) If the priests had slaughtered the goat of the sin-offering, why had they not eaten it? And (2) If the priests were not going to eat it, why did they slaughter it? And immediately thereafter, Leviticus 10:16 reports that Moses “was angry with Eleazar and with Ithamar,” and midrash taught that through becoming angry, he forgot the law. Rabbi Huna taught that this was one of three instances where Moses lost his temper and as a consequence forgot a law. (The other two instances were with regard to the Sabbath in Exodus 16:20 and with regard to the purification of unclean metal utensils Numbers 31:14.) In this case (involving Nadab and Abihu), because of his anger, Moses forgot the law relating to those in the first stage of mourning (the onen), that it is prohibited for a bereaved person, prior to the burial of his dead, to eat consecrated food. Aaron asked Moses whether he should eat consecrated food on the day that his sons died. Aaron argued that since the tithe (which is of lesser sacredness) is forbidden to be eaten by a bereaved person prior to the burial of his dead, how much more certainly must the meat of the sin-offering (which is more sacred) be prohibited to a bereaved person prior to the burial of his dead. Immediately after Moses heard Aaron’s argument, he issued a proclamation to the Israelites, saying that he had made an error in regard to the law and Aaron his brother came and taught him. Eleazar and Ithamar had known the law, but kept their silence out of deference to Moses, and as a reward, God addressed them directly along with Moses and Aaron in Leviticus 11:1. When Leviticus 11:1 reports that “the Lord spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying to them,” Rabbi Hiyya taught that the words “to them” referred to Eleazar and Ithamar. (Leviticus Rabbah 13:1.)

Similarly, Rabbi Nehemiah deduced from Leviticus 10:19 that Aaron's sin-offering was burned (and not eaten by the priests) because Aaron and his remaining sons (the priests) were in the early stages of mourning, and thus disqualified from eating sacrifices. (Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 82b; see also Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a.)

The Rabbis in a Baraita noted the three uses of the word “commanded” in Leviticus 10:12–13, 10:14–15, and Leviticus-nb 10:16–18, in connection with the sacrifices on the eighth day of the inauguration of the Tabernacle, the day on which Nadab and Abihu died. The Rabbis taught that Moses said “as the Lord commanded” in Leviticus 10:13 to instruct that the priest were to eat the grain (minchah) offering, even though they were in the earliest stage of mourning. The Rabbis taught that Moses said “as I commanded” in Leviticus 10:18 in connection with the sin-offering (chatat) at the time that Nadab and Abihu died. And the Rabbis taught that Moses said “as the Lord commanded” in Leviticus 10:15 to enjoin Aaron and the priests to eat the peace-offering (shelamim) notwithstanding their mourning (and Aaron’s correction of Moses in Leviticus 10:19), not just because Moses said so on his own authority, but because God had directed it. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 5b; Zevachim 101a.)

Samuel taught that the interpretation that Aaron should not have eaten the offering agreed with Rabbi Nehemiah while the other interpretation that Aaron should have eaten the offering agreed with Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon. Rabbi Nehemiah argued that they burned the offering because the priests were in the first stages of mourning. Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon maintained that they burned it because the offering had become defiled during the day, not because of bereavement. Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that if it was because of bereavement, they should have burned all three sin offerings brought that day. Alternatively, Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that the priest would have been fit to eat the sacrifices after sunset. Alternatively, Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that Phinehas was with then alive and not restricted by the law of mourning. (Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a.)

According to Rabbi Nehemiah, this is how the exchange went: Moses asked Aaron why he had not eaten the sacrifice. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the blood of the sacrifice had entered the innermost sanctuary, but Aaron answered that its blood had not entered into the inner sanctuary. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the blood had passed outside the sanctuary courtyard, but Aaron replied that it had not. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the priests had offered it in bereavement, and thus disqualified the offering, but Aaron replied that his sons had not offered it, Aaron had. Thereupon Moses exclaimed that Aaron should certainly have eaten it, as Moses had commanded in Leviticus 10:18 that they should eat it in their bereavement. Aaron replied with Leviticus 10:19 and argued that perhaps what Moses had heard was that it was allowable for those in mourning to eat the special sacrifices for the inauguration of the Tabernacle, but not the regular ongoing sacrifices. For if Deuteronomy 26:14 instructs that the tithe, which is of lesser holiness, cannot be eaten in mourning, how much more should that prohibition apply to sacrifices like the sin-offering that are more holy. When Moses heard that argument, he replied with Leviticus 10:20 that it was pleasing to him, and he admitted his error. Moses did not seek to excuse himself by saying that he had not heard the law from God, but admitted that he had heard it and forgot it. (Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a.)

According to Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon, this is how the exchange went: Moses asked Aaron why he had not eaten, suggesting the possibilities that the blood had entered the innermost sanctuary or passed outside the courtyard or been defiled by being offered by his sons, and Aaron said that it had not. Moses then asked whether perhaps Aaron had been negligent through his grief and allowed the sacrifice to become defiled, but Aaron exclaimed with Leviticus 10:19 that these events and even more could have befallen him, but Aaron would not show such disrespect to sacrifices. Thereupon Moses exclaimed that Aaron should certainly have eaten it, as Moses had commanded in Leviticus 10:18. Aaron argued from analogy to the tithe (as in Rabbi Nehemiah’s version), and Moses accepted Aaron’s argument. But Moses argued that the priests should have kept the sacrificial meat and eaten it in the evening. And to that Aaron replied that the meat had accidentally become defiled after the sacrifice. (Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a–b.)

A Baraita taught that the righteous are blessed, for not only do they acquire merit, but they bestow merit on their children and children's children to the end of all generations. The Baraita deduced from the words “that were left” used in Leviticus 10:12 to describe Aaron’s remaining sons that those sons deserved to be burned like Nadab and Abihu, but Aaron’s merit helped them avoid that fate. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 87a.)

Leviticus chapter 11

Tractate Chullin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Talmud interpreted the laws of kashrut in Leviticus 11. (Mishnah Chullin 1:1–12:5; Tosefta Chullin 1:1–10:16; Babylonian Talmud Chullin 2a–142a.)

A midrash taught that Adam offered an ox as a sacrifice, anticipating the laws of clean animals in Leviticus 11:1–8. (Leviticus Rabbah 2:10.)

Commandments

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 6 positive and 11 negative commandments in the parshah:

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple with long hair. Leviticus 10:6.

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple with torn clothes. Leviticus 10:6.

- A Kohen must not leave the Temple during service. Leviticus 10:7.

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple intoxicated. Leviticus 10:9.

- To examine the signs of animals to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher Leviticus 11:2.

- Not to eat non-kosher animals Leviticus 11:4.

- To examine the signs of fish to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher Leviticus 11:9.

- Not to eat non-kosher fish Leviticus 11:11.

- Not to eat non-kosher fowl Leviticus 11:13.

- To examine the signs of locusts to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher Leviticus 11:21.

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by the eight insects Leviticus 11:29.

- To observe the laws of impurity concerning liquid and solid foods Leviticus 11:34.

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by a dead beast Leviticus 11:39.

- Not to eat non-kosher creatures that crawl on land Leviticus 11:41.

- Not to eat worms found in fruit on the ground Leviticus 11:42.

- Not to eat creatures that live in water other than fish Leviticus 11:43.

- Not to eat non-kosher maggots Leviticus 11:44.

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 2:131–99. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1984. ISBN 0-87306-296-5.)

Haftarah

The Chastisement of Uzzah (illustration by James Tissot)

In general

The haftarah for the parshah is:

Summary

David gathered together all the chosen men of Israel — 30,000 in all — and went to retrieve the Ark of the Covenant from Baale-judah. (2Samuel 6:1–2.) They brought the Ark out of the house of Abinadab and set it on a new cart, and Abinadab’s sons Uzzah and Ahio drove the cart, with Ahio going before the Ark. (2Samuel 6:3–4.) David and the Israelites played with all manner of instruments — harps, psalteries, timbrels, sistra, and cymbals. (2Samuel 6:5.) When they came to the threshing-floor of Nacon, the oxen stumbled, and Uzzah put out his hand to the Ark. (2Samuel 6:6.) In anger, God smote Uzzah for his error, and Uzzah died by the Ark. (2Samuel 6:7.)

Displeased and afraid, David questioned how the Ark could come to him. (2Samuel 6:8–9.) So David took the Ark to the house of Obed-Edom the Gittite and left it there for three months, during which time God blessed Obed-Edom and his house. (2Samuel 6:10–11.)

The Ark of Jerusalem (woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld)

When David heard that God had blessed Obed-Edom because of the Ark, David brought the Ark to Jerusalem with joy. (2Samuel 6:12.) When those who bore the Ark had gone six paces, they sacrificed an ox and a fatling. (2Samuel 6:13.) The Israelites brought up the Ark with shouting and the sound of the horn, and David danced with all his might girded with a linen ephod. (2Samuel 6:14–15.) As the Ark came into the city, Michal the daughter of Saul looked out the window and saw David leaping and dancing, and she despised him in her heart. (2Samuel 6:16.)

They set the Ark in a tent that David pitched for it, David offered burnt-offerings and peace-offerings, and David blessed the people in the name of the Lord. (2Samuel 6:17–18.) David distributed a sweet cake of bread to all the people of Israel, and the people departed to their houses. (2Samuel 6:19.) (The Haftarah ends at this point for Sephardi Jews, but continues for Ashkenazi Jews.) When David returned to bless his household, Michal came out to meet him with scorn, taunting him for uncovering himself before his servants’ handmaids. (2Samuel 6:20.) David retorted to Michal that he danced before the God who had chosen him over her father, and that he would be viler than that. (2Samuel 6:21–22.) Michal never had children thereafter. (2Samuel 6:23.)

God gave David rest from his enemies, and David asked Nathan the prophet why David should dwell in a house of cedar, while the Ark dwelt within curtains. (2Samuel 7:1–2.) At first Nathan told David to do what was in his heart, but that same night God directed Nathan to tell David not to build God a house, for God had not dwelt in a house since the day that God had brought the children of Israel out of Egypt, but had abided in a tent and in a tabernacle. (2Samuel 7:3–7.) God directed Nathan to tell David that God took David from following sheep to be a prince over Israel, God had been with David wherever he went, and God would make David a great name. (2Samuel 7:8–9.) God would provide a place for the Israelites at rest from their enemies, God would make David into a dynasty, and when David died, God would see that David’s son would build a house for God’s name. (2Samuel 7:10–13.) God would be to David’s son a father, and he would be to God a son; if he strayed, God would chasten him, but God’s mercy would not depart from him. (2Samuel 7:14–15.) David’s kingdom would be established forever. (2Samuel 7:16.) And Nathan told David everything in his vision. (2Samuel 7:17.)

Connection to the parshah

Both the parshah and the haftarah report efforts to consecrate the holy space followed by tragic incidents connected with inappropriate proximity to the holy space. In the parshah, Moses consecrated the Tabernacle, the home of the Ark of the Covenant (Leviticus 9), while in the haftarah, David set out to bring the Ark to Jerusalem. (2Samuel 6:2–5.) Then in the parshah, God killed Nadab and Abihu “when they drew near” to the Ark (Leviticus 16:1–2), while in the haftarah, God killed Uzzah when he “put forth his hand to the Ark.” (2Samuel 6:6–7.)

Ezekiel (painting by Michelangelo)

On Shabbat Parah

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat Parah (the special Sabbath prior to Passover — as it does in 2011 and 2014), the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–38.

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–36.

On Shabbat Parah, the Sabbath of the red heifer, Jews read Numbers 19:1–22, which describes the rites of purification using the red heifer (parah adumah). Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 36 also describes purification. In both the special reading and the haftarah in Ezekiel 36, sprinkled water cleansed the Israelites. (Num. 19:18; Ezek. 36:25.)

On Shabbat Machar Chodesh

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat Machar Chodesh (as it does in 2012 and 2015), the haftarah is 1Samuel 20:18–42.

Further reading

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Leviticus 16:1–2 (Nadab and Abihu).

- Numbers 3:4 (Nadab and Abihu); 26:61 (Nadab and Abihu).

- Deuteronomy 14:3–21 (kashrut).

Philo

Early nonrabbinic

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 2:15:57–58, 26:104–05; 3:47:139–48:141, 49:144, 50:147; On Husbandry 30:131–35; On Drunkenness 32:126–27, 35:140–41; On the Migration of Abraham 12:64–69; Who Is the Heir of Divine Things? 49:238–40, 51:249–51; On Flight and Finding'On Flight and Finding 11:59, 28:157; On Dreams, That They Are God-Sent 2:9:67; The Special Laws 2:8:33; 4:18:105–06, 20:110, 21:113–22:118, 36:191.Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century C.E.. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 44, 49, 66–67, 185, 218–19, 259, 296, 298, 326, 335, 392, 571, 626–27, 635. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

Josephus

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:8:6–7; 8:8:4. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 92, 229. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Sheviit 5:9, 7:4; Bikkurim 2:7, 11; Sotah 5:2; Menachot 5:6; Chullin 1:1–12:5. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 81, 84, 171–72, 455, 743, 765–87. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Berakhot 4:17; Demai 2:7; Sotah 5:13; Zevachim 8:25; Chullin 1:1–10:16; Parah 1:5. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:26, 85, 853; 2:1347, 1371–1405, 1746. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifra 99:1–121:2:13. Land of Israel, 4th Century C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 2:121–229. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-206-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Peah 12b; Sheviit 55b; Maasrot 41a; Orlah 34a; Bikkurim 12b. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 3, 6b, 9, 12. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006–2009.

- Leviticus Rabbah 1:8; 2:10; 10:4; 11:1–14:1; 20:4–5, 8–10; 26:1. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, 4:12, 29, 125, 135–79, 257–62, 325. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

Talmud

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 53b, 61a; Shabbat 12a, 27a, 63b–64a, 83b–84a, 87b, 90b, 95b, 107a, 123b, 125a, 136a–b; Eruvin 13b, 28a, 63a, 87b, 104b; Pesachim 14a, 16a, 18a–b, 20b, 23a–b, 24b, 49b, 67b, 82b–83a, 91b; Yoma 2b–4a, 5b, 21b, 39a, 53a, 73b, 76b, 80a–b, 87a; Sukkah 25b; Beitzah 6b, 19a, 20a; Rosh Hashanah 16b; Taanit 15b, 17b, 26b; Megillah 9b, 10b, 18a; Moed Katan 2a, 13a–b, 14b–15b, 19b, 24a, 28b; Chagigah 11a, 19a, 22b, 24a, 26b; Yevamot 20b, 40a, 43a, 54a–b, 74b–75a, 87a, 114a; Ketubot 15a, 50a, 60a; Nazir 4a, 38a, 52a, 64a; Sotah 27b, 29a–b, 38a–b, 47a; Gittin 60a, 61b–62a, 68b; Kiddushin 30a, 59b, 80a; Bava Kamma 2a–b, 16a, 25b, 38a, 54a–b, 62b–63a, 64b, 76b–77a, 78a, 81a; Bava Metzia 22a, 61b, 90b; Bava Batra 9b, 66b, 80a, 91a, 97a; Sanhedrin 5b, 17a, 22b, 52a, 70b–71a, 83b, 107b, 108b; Makkot 3b, 11a, 13a, 16b; Shevuot 5a, 7a, 9b–10b, 14b, 18b, 23a, 36b; Avodah Zarah 40a, 47b, 68b; Horayot 4a; Zevachim 3a–b, 10b, 17b, 25b, 28a, 34a, 55a, 60a, 61b, 69b, 82a–b, 99b, 100b–01b, 105a, 115b; Menachot 23a, 29a, 39b, 59a, 62a, 70b, 93b, 96b, 101b; Chullin 2a–142a; Bekhorot 6a–7b, 9b, 15b, 16a, 38a, 45b, 51a; Keritot 4b, 13b, 15b, 21a, 22a; Meilah 16a–17b; Tamid 33b; Niddah 18a, 19b, 21a, 42b, 51a–b, 55b, 56a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Rashi

Medieval

- Saadia Gaon. The Book of Beliefs and Opinions, 10:15. Baghdad, Babylonia, 933. Translated by Samuel Rosenblatt, 396. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1948. ISBN 0-300-04490-9.

- Solomon ibn Gabirol. A Crown for the King, 35:470. Spain, 11th Century. Translated by David R. Slavitt, 62–63. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-511962-2.

- Rashi. Commentary. Leviticus 9–11. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 3:93–134. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-028-5.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 3:31. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 165. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

Maimonides

- Maimonides. Guide for the Perplexed, 1:37; 3:46, 47, 48. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, 53, 364, 367–68, 370. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Zohar 1:54a, 73b, 167b; 2:11b, 26b, 67a, 124b, 193a, 219b; 3:24b, 31b, 33a, 35a–42a, 127a, 190b. Spain, late 13th Century.

Modern

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, 47–50, 211, 314–31, 338, 574, 582–86. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 ISBN 0-900689-40-4. Originally published as Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel’s Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. Germany, 1837.

- Louis Ginzberg. Legends of the Jews, 3:179–92. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1911.

Hirsch

- Abraham Isaac Kook. The Moral Principles. Early 20th Century. Reprinted in Abraham Isaac Kook: the Lights of Penitence, the Moral Principles, Lights of Holiness, Essays, Letters, and Poems. Translated by Ben Zion Bokser, 140. Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press 1978. ISBN 0-8091-2159-X.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 256–57, 348. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- Jacob Milgrom. "Ethics and Ritual: The Foundations of the Biblical Dietary Laws." In Religion and Law: Biblical, Jewish, and Islamic Perspectives, 159–91. Edited by E.B. Firmage. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1989. ISBN 0931464390.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Food and Faith: The Ethical Foundations of the Biblical Diet Laws: The Bible has worked out a system of restrictions whereby humans may satiate their lust for animal flesh and not be dehumanized. These laws teach reverence for life.” Bible Review. 8 (6) (Dec. 1992).

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 1-16, 3:569–742. New York: Anchor Bible, 1998. ISBN 0-385-11434-6.

Wiesel

- Elie Wiesel. “Nadab and Abihu: A Story of Fire and Silence.” In Wise Men and Their Tales: Portraits of Biblical, Talmudic, and Hasidic Masters, 68–81. New York: Schocken, 2003. ISBN 0-8052-4173-6.

- Naphtali S. Meshel. “Food for Thought: Systems of Categorization in Leviticus 11.” Harvard Theological Review. 101 (2) (Apr. 2008): 203–29.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||

yi:שמיני