| Part of the series on Pope (Catholic Church) | |

|---|---|

| Coat of Arms of the Holy See. | |

| History | |

| Saint Peter and the origin of the office | |

| Election, death and abdication | |

| Titles | |

| Residence and jurisdiction | |

| Regalia and insignia | |

| Status and authority | |

| Political role | |

| Objections to the papacy | |

| Antipopes | |

| Other popes | |

| Longest-reigning popes | |

| Shortest-reigning popes | |

| Article discussion | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Organization |

| Pope – Pope Francis |

| College of Cardinals |

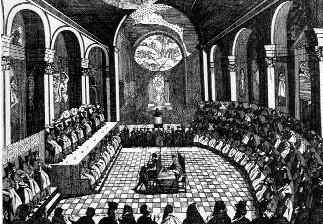

| Ecumenical Councils |

| Episcopal polity · Latin Rite |

| Eastern Catholic Churches |

| Background |

| History · Christianity |

| Catholicism · Apostolic Succession |

| Four Marks of the Church |

| Ten Commandments |

| Crucifixion & Resurrection of Jesus |

| Ascension · Assumption of Mary |

| Criticism of the Catholic Church |

| Theology |

| Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) |

| Theology · Apologetics |

| Divine Grace · Sacraments |

| Purgatory · Salvation |

| Original sin · Saints · Dogma |

| Virgin Mary · Mariology |

| Immaculate Conception of Mary |

| Liturgy and Worship |

| Roman Catholic Liturgy |

| Eucharist · Liturgy of the Hours |

| Liturgical Year · Biblical Canon |

| Rites |

| Roman · Armenian · Alexandrian |

| Byzantine · Antiochian · East Syrian |

| Catholicism topics |

| Ecumenism · Monasticism |

| Prayer · Music · Art |

Catholics recognize the Pope as a successor to Saint Peter, whom, according to the Bible, Jesus named as the "shepherd" and "rock" of the Church.[1][2] Peter never bore the title of "Pope", which came into use much later, but Catholics recognize him as the first Pope,[3] while official declarations of the Church only speak of the Popes as holding within the college of the Bishops a position analogous to that held by Peter within the college of the Apostles, of which the college of the Bishops, a distinct entity, is the successor.[4][5][6]

The study of the New Testament offers no uncontested proof that Jesus established the papacy nor even that he established Peter as the first bishop of Rome.[7] The Catholic Church does not say that Jesus personally appointed Peter bishop of Rome and in its dogmatic constitution Lumen Gentium makes a clear distinction between apostles and bishops, presenting the latter as the successors of the former, with the Pope as successor of Peter in that he is head of the bishops as Peter was head of the apostles.[8] Some historians have argued that the notion that Peter was the first bishop of Rome and founded the Christian church there can be traced back no earlier than the third century.[9] The writings of the Church Father Irenaeus who wrote around 180 AD indicate a belief that Peter "founded and organised" the Church at Rome.[10] However, Irenaeus was not the first to write of Peter's presence in the early Roman Church. Clement of Rome wrote in a letter to the Corinthians, c. 96[11] about the awesome persecution of Christians in Rome as the “struggles in our time” and presented to the Corinthians its heroes, “first, the greatest and most just columns, the “good apostles” Peter and Paul.[12] St. Ignatius of Antioch wrote shortly after Clement and in his letter from the city of Smyrna to the Romans he said he would not command them as Peter and Paul did.[13] Given this and other evidence, many scholars conclude that Peter was indeed martyred in Rome under Nero.[14]

Various Christian communities would have had a group of presbyter-bishops functioning as leaders of the local church. Eventually this evolved into a monarchical episcopacy in certain cities.[15] Some historians would argue that it is possible that the monarchical episcopacy probably developed in other churches in the Christian world before it took shape in Rome. For example, it has been conjectured that Antioch may have been one of the first Christian communities to have adopted such a structure.[15] Indeed, in Rome there were many who claimed to be the rightful bishop though again Irenaeus stressed the validity of one line of bishops from the time of St. Peter up to his contemporary Pope Victor I and listed them.[16] Some writers claim that the emergence of a single bishop in Rome probably did not arise until the middle of the second century. In their view, Linus, Cletus and Clement were possibly prominent presbyter-bishops but not necessarily monarchical bishops.[9] Though this would not necessarily affect their authority as Popes in terms of Catholic Theology.

The see of Rome was early accorded prominence in issues related to matters of the universal church.[17]

Early Christianity (c. 30 – 325)[]

It seems that at first the terms 'episcopos' and 'presbyter' were used interchangeably.[18] The general consensus among scholars has been that, at the turn of the first and second centuries, local congregations were led by bishops and presbyters whose offices were overlapping or indistinguishable.[19] There was probably no single 'monarchical' bishop in Rome before the middle of the second century ... and likely later."[20]

In the early Christian era, Rome and a few other cities had claims on the leadership of worldwide ("Catholic") church. James the Just, known as "the brother of the Lord", served as head of the Jerusalem church, which is still honored as the "Mother Church" in Orthodox tradition. Alexandria had been a center of Jewish learning and became a center of Christian learning. Rome had a large congregation early in the apostolic period whom Paul the Apostle addressed in his Epistle to the Romans, and Paul himself was martyred there.

During the first century of the Christian Church (ca. 30–130), the Roman capital became recognized as a Christian center of exceptional importance. Pope Clement I at the end of the 1st century wrote an epistle to the Church in Corinth, Greece, intervening in a major dispute, and apologising for not having taken action earlier.[21] However, there are only a few other references of that time to recognition of the authoritative primacy of the Roman See outside of Rome. In the Ravenna Document of 13 October 2007, theologians chosen by the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches stated: "41. Both sides agree ... that Rome, as the Church that 'presides in love' according to the phrase of St Ignatius of Antioch (To the Romans, Prologue), occupied the first place in the taxis, and that the bishop of Rome was therefore the protos among the patriarchs. They disagree, however, on the interpretation of the historical evidence from this era regarding the prerogatives of the Bishop of Rome as protos, a matter that was already understood in different ways in the first millennium." In addition, in the last years of the first century AD the Church in Rome intervened in the affairs of the Christian Church in Corinth to help solve their internal disputes.

Later in the second century AD, there were further manifestations of Roman authority over other churches. In 189 AD, assertion of the primacy of the Church of Rome may be indicated in Irenaeus of Lyons's Against Heresies (3:3:2): "With [the Church of Rome], because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree... and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition." And in 195 AD, Pope Victor I, in what is seen as an exercise of Roman authority over other churches, excommunicated the Quartodecimans for observing Easter on the 14th of Nisan, the date of the Jewish Passover, a tradition handed down by St. John the Evangelist (see Easter controversy). Celebration of Easter on a Sunday, as insisted on by the Pope, is the system that has prevailed (see computus).

Early popes helped spread Christianity and resolve doctrinal disputes.[22]

Nicea to East-West Schism (325–1054)[]

During these seven centuries, the church unified by Emperor Constantine effectively split into a Greek East and a Latin West. The pope became independent of the Emperor in the East, and became a major force in politics in the West.

Imperial capitals: Rome and Constantinople[]

With the conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity and the Council of Nicea, the Christian religion received imperial backing.

At the time of the Council (325), Rome was still seen as the capital of the empire, although the emperor rarely lived there. With the establishment of a new fixed capital in Constantinople (330), there arose a new centre, which soon grew in prominence, rivalling those in Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, which previously had been the most important centres of Christianity.

Of these, Rome claimed the chief place, as illustrated by Pope Leo the Great's statement, in about 446, that "the care of the universal Church should converge towards Peter's one seat, and nothing anywhere should be separated from its Head",[23] clearly articulating the extension of papal authority as doctrine, and promulgating his right to exercise "the full range of apostolic powers that Jesus had first bestowed on the apostle Peter".

The early ecumenical councils, particularly the First Council of Constantinople (381), affirmed the importance of the Bishop of Rome's position, though all the councils in the Church's early history took place in cities in the East, and the Pope did not personally attend the council in 381. It was at the ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 that Leo I (through his emissaries) stated that he was "speaking with the voice of Peter". At this same council, the Bishop of Constantinople was given "equal privileges" to those of the Bishop of Rome, because "Constantinople is the New Rome". Pope Leo rejected this decree on the ground that it contravened the sixth canon of Nicaea and infringed the rights of Alexandria and Antioch.[24]

Medieval development[]

Gregory the Great (c 540–604) who established medieval themes in the Church, in a painting by Carlo Saraceni, circa 1610, Rome.

After the fall of Rome, the pope served as a source of authority and continuity. Gregory the Great (c 540–604) administered the church with stern reform.[25] From an ancient senatorial family, Gregory worked with the stern judgment and discipline typical of ancient Roman rule.[25] Theologically, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook, his popular writings full of dramatic miracles, potent relics, demons, angels, ghosts, and the approaching end of the world.[25]

Gregory's successors were mostly dominated by the exarch or the Eastern emperor.[25] These humiliations, the weakening of the Empire in the face of Muslim expansion, and the inability of the Emperor to protect the papal estates made Pope Stephen II turn from the Emperor.[25] Seeking protection against the Lombards and getting no help from Emperor Constantine V, the pope appealed to the Franks to protect his lands.[25] Pepin the Short subdued the Lombards and donated Italian land to the Papacy.[25] When Leo III crowned Charlemagne (800), he established the precedent that no man would be emperor without anointment by a pope.[25]

Around 850, a forger, probably from among the French opposers of Hincmar, Archbishop of Reims[26] made a collection of church legislation that contained forgeries as well as genuine documents.[26][27] At first some attacked it as false, but it was taken as genuine throughout the rest of the Middle Ages[26] It is now known as the False Decretals. It was part of a series of falsifications of past legislation by a party in the Carolingian Empire whose principal aim was to free the church and the bishops from interference by the state and the metropolitans respectively,[26][27] and who were concerned for papal supremacy as guaranteeing those rights.[26] The author, a French cleric calling himself Isidore Mercator, created false documents purportedly by early church popes, demonstrating that supremacy of the papacy dated back to the church's oldest traditions.[25] The decretals include the Donation of Constantine, in which Constantine grants Pope Sylvester I secular authority over all Western Europe.[28] Thanks to this forgery in the collection, the decretals became one of the most persuasive forgeries in the history of the West. It supported Papal policies for centuries.[25]

Pope Nicholas I (858–867) asserted that the pope should have suzerain authority over all Christians, even royalty, in matters of faith and morals.[25] Only Photius, bishop of Constantinople, dared gainsay him.[25] He sternly defended morality and justice in a decadent age.[25] After his death, the authority of the papacy was acknowledged more widely than ever before.[25]

The low point of the Papacy was 867–1049.[29] The Papacy came under the control of vying political factions.[29] Popes were variously imprisoned, starved, killed, and deposed by force.[29] The family of a certain papal official made and unmade popes for fifty years.[29] The official's great-grandson, Pope John XII, held orgies of debauchery in the Lateran palace.[29] Emperor Otto I of Germany had John accused in an ecclesiastical court, which deposed him and elected a layman as Pope Leo VIII.[29] John mutilated the Imperial representatives in Rome and had himself reinstated as Pope.[29] Conflict between the Emperor and the papacy continued, and eventually dukes in league with the emperor were buying bishops and popes almost openly.[29]

In 1049, Leo IX became pope, at last a pope with the character to face the papacy's problems.[29] He traveled to the major cities of Europe to deal with the church's moral problems firsthand, notably the sale of church offices or services (simony) and clerical marriage and concubinage.[29] With his long journey, he restored the prestige of the Papacy in the north.[29]

East–West Schism to Reformation (1054–1517)[]

Historical map of the Western Schism: red is support for Avignon, blue for Rome

The East and West churches split definitively in 1054. This split was caused more by political events than by slight diversities of creed.[29] Popes had galled the emperors by siding with the king of the Franks, crowning a rival Roman emperor, appropriating the exarchate of Ravenna, and driving into Greek Italy.[29]

In the Middle Ages, popes struggled with monarchs over power.[22]

From 1309 to 1377, the pope resided not in Rome but in Avignon (see Avignon Papacy). The Avignon Papacy was notorious for greed and corruption.[30] During this period, the pope was effectively an ally of France, alienating France's enemies, such as England.[31]

The pope was understood to have the power to draw on the "treasury" of merit built up by the saints and by Christ, so that he could grant indulgences, reducing one's time in purgatory.[30] The concept that a monetary fine or donation accompanied contrition, confession, and prayer eventually gave way to the common understanding that indulgences depended on a simple monetary contribution.[30] Popes condemned misunderstandings and abuses but were too pressed for income to exercise effective control over indulgences.[30]

Popes also contended with the cardinals, who sometimes attempted to assert the authority of councils over the pope's. Conciliar theory holds that the supreme authority of the church lies with a General Council, not with the pope.[32] Its foundations were laid early in the 13th century, and it culminated in the 15th century.[32] The failure of the conciliar theory to win general acceptance after the 15th century is taken as a factor in the Protestant Reformation.[32]

Various antipopes challenged papal authority, especially during the Western Schism (1378–1417). In this schism, the papacy had returned to Rome from Avignon, but an antipope was installed in Avignon, as if to extend the papacy there.

The Eastern Church continued to decline with the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, undercutting Constantinople's claim to equality with Rome. Twice an Eastern Emperor tried to force the Eastern Church to reunify with the West. Papal claims of superiority were a sticking point in reunification, which failed in any event. In the 15th century, the Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople.

Reformation to present (1517 to today)[]

As part of the Catholic Reformation, Pope Paul III (1534–1549) initiated the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which established the triumph of the Papacy over those who sought to reconcile with Protestants or oppose Papal claims.

Protestant Reformers criticized the Papacy as corrupt and characterized the pope as the antichrist.

Popes instituted the Catholic Reformation[22] (1560–1648), which addressed challenges of the Protestant Reformation and instituted internal reforms. Pope Paul III (1534–1549) initiated the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which established the triumph of the Papacy over rulers who sought to reconcile with Protestants and against French and Spanish bishops opposed to Papal claims.[33]

Gradually forced to give up secular power, popes focused on spiritual issues.[22]

The pope's claims of spiritual authority have been ever more clearly expressed since the first centuries. In 1870, the First Vatican Council proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility for those rare occasions the pope speaks ex cathedra (literally "from the chair (of Peter)") when issuing a solemn definition of faith or morals.[22]

Later in 1870, Victor Emmanuel II seized Rome from the pope's control and substantially completed the unification of Italy.[22] The Papal States that the pope lost had been used to support papal independence.[22]

In 1929, the Lateran Treaty between Italy and Pope Pius XI established the Vatican guaranteed papal independence from secular rule.[22]

In 1950, the pope defined the Assumption of Mary as dogma, the only time that a pope has spoken ex cathedra since papal infallibility was explicitly declared.

The Petrine Doctrine is still controversial as an issue of doctrine that continues to divide the eastern and western churches as well as separating Protestants from Rome.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Vatican Library. http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p123a9p4.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-02., 880-884

- ↑ "St. Peter, The Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ Wilken, p. 281, quote: "Some (Christian communities) had been founded by Peter, the disciple Jesus designated as the founder of his church. ... Once the position was institutionalized, historians looked back and recognized Peter as the first pope of the Christian church in Rome"

- ↑ Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, 22

- ↑ [http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/audiences/alpha/data/aud19921007en.html Pope John Paul II, Talk on 7 October 1992

- ↑ Avery Dulles, The Catholicity of the Church, Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 0198266952, page 140

- ↑ O'Grady, John. The Roman Catholic church: its origins and nature. p. 143.

- ↑ Lumen gentium, 22

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 O'Grady, John. The Roman Catholic church: its origins and nature. p. 146.

- ↑ Stevenson, J.. A New Eusebius. p. 114.

- ↑ "Letter of Clement to the Corinthians". http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1010.htm.

- ↑ Gröber, 510

- ↑ "Letter of Ignatius of Antioch to the Romans". http://www.crossroadsinitiative.com/library_article/244/Letter_of_Ignatius_of_Antioch_to_the_Romans.html.

- ↑ "[M]any scholars ... accept Rome as the location of the martyrdom and the reign of Nero as the time." Daniel William O’Connor, "Saint Peter the Apostle." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 25 Nov. 2009 [1].

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 O'Grady, John. The Roman Catholic church: its origins and nature. p. 140.

- ↑ Stevenson, J.. A New Eusebius. p. 114-115.

- ↑ "From an historical perspective, there is no conclusive documentary evidence from the first century or the early decades of the second of the exercise of, or even the claim to, a primacy of the Roman bishop or to a connection with Peter, although documents from this period accord the church at Rome some kind of pre‑eminence" (Emmanuel Clapsis, Papal Primacy, extract from Orthodoxy in Conversation (2000), p. 110]); and "The see of Rome, whose prominence was associated with the deaths of Peter and Paul, became the principle centre in matters concerning the universal Church" (Clapsis, p. 102). The same writer quotes with approval the words of Joseph Ratzinger: "In Phanar, on 25 July 1976, when Patriarch Athenegoras addressed the visiting pope as Peter's successor, the first in honour among us, and the presider over charity, this great church leader was expressing the essential content of the declarations of the primacy of the first millennium" (Clapsis, p. 113).

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 1997 edition revised 2005, page 211: "It seems that at first the terms 'episcopos' and 'presbyter' were used interchangeably ..."

- ↑ Cambridge History of Christianity, volume 1, 2006, "The general consensus among scholars has been that, at the turn of the first and second centuries, local congregations were led by bishops and presbyters whose offices were overlapping or indistinguishable."

- ↑ Cambridge History of Christianity, volume 1, 2006, page 418: "Probably there was no single 'monarchical' bishop in Rome before the middle of the second century ... and likely later."

- ↑ Chadwick, Henry, Oxford History of Christianity, OUP, quote: "Towards the latter part of the 1st century, Rome's presiding cleric named Clement wrote on behalf of his church to remonstrate with the Corinthian Christians who had ejected clergy without either financial or charismatic endowment in favour of a fresh lot; Clement apologized not for intervening but for not having acted sooner. Moreover, during the second century the Roman community's leadership was evident in its generous alms to poorer churches. About 165 they erected monuments to their martyred apostles, to Peter in a necropolis on the Vatican Hill, to Paul on the road to Ostia, at the traditional sites of their burial. Roman bishops were already conscious of being custodians of the authentic tradition of true interpretation of the apostolic writings. In the conflict with Gnosticism Rome played a decisive role, and likewise in the deep division in Asia Minor created by the claims of the Montanist prophets.."

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt and company. 1994.

- ↑ Letter XIV

- ↑ Council of Chalcedon (1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica)

- ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 25.11 25.12 25.13 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedAF:CC - ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 "False Decretals." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Encyclopaedia Britannica: False Decretals

- ↑ Durant, Will. The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972. p. 525–526

- ↑ 29.00 29.01 29.02 29.03 29.04 29.05 29.06 29.07 29.08 29.09 29.10 29.11 29.12 Durant, Will. The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Durant, Will. The Reformation. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1957. "Chapter I. The Roman Catholic Church." 1300-1517. p. 3–25

- ↑ Durant, Will. The Reformation. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1957. "Chapter II. England: Wyclif, Chaucer, and the Great Revolt." 1308-1400. p. 26–57

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Conciliar theory." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ "Counter-Reformation." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005