Shemot, Shemoth, or Shemos (שמות — Hebrew for “names,” the second word, and first distinctive word, of the parsha) is the thirteenth weekly Torah portion (parsha) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the first in the book of Exodus. It constitutes Exodus 1:1–6:1. Jews in the Diaspora read it the thirteenth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in late December or January.

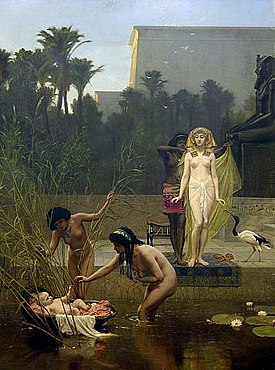

Pharaoh's daughter finds Moses in the Nile (1886 painting by Edwin Long)

Summary[]

Israel in Egypt (1867 painting by Edward Poynter)

Pharaoh Notes the Importance of the Jewish People (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Affliction in Egypt[]

Seventy descendants of Jacob came down to Egypt, and the Israelites were fruitful and filled the land. (Exodus 1:1–7.) Joseph and all of his generation died, and a new Pharaoh arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph. (Exodus 1:6–8.) He told his people that the Israelites had become too numerous and required shrewd dealing, lest they multiply and in a war join Egypt's enemies. (Exodus 1:9–10.) Therefore, the Egyptians set taskmasters over the Israelites to afflict them with burdens — and the Israelites built store-cities for Pharaoh, Pithom and Raamses — but the more that the Egyptians afflicted them, the more that they multiplied. (Exodus 1:11–12.) The Egyptians embittered the Israelites’ lives with hard service in brick and mortar and in the field. (Exodus 1:14.)

Pharaoh told the Hebrew midwives, who were named Shiphrah and Puah, that when they delivered Hebrew women, they were to kill the sons, but let the daughters live. (Exodus 1:15–16.) But the midwives feared God, and disobeyed Pharaoh, saving the baby boys. (Exodus 1:17.) Pharaoh asked the midwives why they had saved the boys, and the midwives told Pharaoh that the Hebrew women were more vigorous than the Egyptian women and delivered before a midwife could get to them. (Exodus 1:18–19.) God rewarded the midwives because they feared God, and God made them houses. (Exodus 1:20–21.) The Israelites continued to multiply, and Pharaoh charged all his people to cast every newborn boy into the river, leaving the girls alive. (Exodus 1:21–22.)

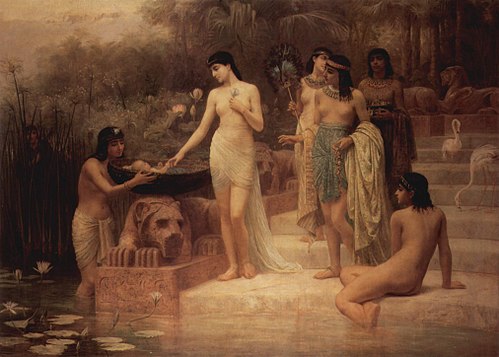

The Finding of Moses (1904 painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema)

Baby Moses[]

Pharaoh's Daughter Receives the Mother of Moses (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

A Levite couple had a baby boy, and the woman hid him three months. (Exodus 2:1–2.) When she could not longer hide him, she made an ark of bulrushes, daubed it with slime and pitch, put the boy inside, and laid it in river. (Exodus 2:3.) As his sister watched, Pharaoh's daughter came to bathe in the river, saw the ark, and sent her handmaid to fetch it. (Exodus 2:4–5.) She opened it, saw the crying boy, and had compassion on him, recognizing that he was one of the Hebrew children. (Exodus 2:6.)

His sister asked Pharaoh's daughter whether she should call a nurse from the Hebrew women, and Pharaoh's daughter agreed. (Exodus 2:7.) The girl called the child's mother, and Pharaoh's daughter hired her to nurse the child for her. (Exodus 2:8–9.) When the child grew, his mother brought him to Pharaoh's daughter, who adopted him as her son, calling him Moses, because she drew him out of the water. (Exodus 2:10.)

When Moses grew up, he went to his brethren and saw their burdens. (Exodus 2:11.) He saw an Egyptian striking a Hebrew, he looked this way and that, and when he saw no one, he struck the Egyptian and hid him in the sand. (Exodus 2:11–12.) When he went out the second day, he came upon two Hebrew men fighting, and he asked the wrongdoer why he struck his fellow. (Exodus 2:13.) The man asked Moses who had made him king, asking him whether he intended to kill him as he did the Egyptian, so Moses realized that his deed was known. (Exodus 2:14.) When Pharaoh heard, he sought to kill Moses, but Moses fled to Midian, where he sat down by a well. (Exodus 2:15.)

Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro (painting circa 1523 by Rosso Fiorentino)

Moses and the Daughters of Jethro (painting circa 1660–1689 by Ciro Ferri)

Moses in Midian[]

The priest of Midian's seven daughters had come to water their father's flock, but shepherds drove them away. (Exodus 2:16–17.) Moses stood up and helped the daughters, and watered their flock. (Exodus 2:17.) When they came home to their father Reuel, he asked how they were able to come home so early, and they explained how an Egyptian had delivered them from the shepherds, and had also drawn water for the flock. (Exodus 2:18–19.) Reuel then asked his daughters why they had left the man there, and told them to call him back to join them for a meal. (Exodus 2:20.)

Moses was content to live with the man, and he gave Moses his daughter Zipporah to marry. (Exodus 2:21.) Moses and Zipporah had a baby boy, whom Moses called Gershom, saying that he had been a stranger in a strange land. (Exodus 2:22.)

The calling of Moses[]

The Pharaoh died, and the Israelites groaned under their bondage and cried to God, and God heard them and remembered God's covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. (Exodus 2:23–25.)

When Moses was keeping his father-in-law Jethro’s flock at the mountain of God, Horeb (another name for the Biblical Mount Sinai), the angel of God appeared to him in a flame in the midst of a bush that burned but was not consumed. (Exodus 3:1–2.) God called to Moses from the bush, and Moses answered: “Here I am.” (Exodus 3:4.) God told Moses not to draw near, and to take off his shoes, for the place on which he stood was holy ground. (Exodus 3:5.) God identified as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, reported having seen the Israelites’ affliction and heard their cry, and promised to deliver them from Egypt to Canaan, a land flowing with milk and honey. (Exodus 3:6–8.) God told Moses that God was sending Moses to Pharaoh to bring the Israelites out of Egypt, but Moses asked who he was that he should do so. (Exodus 3:10–11.) God told Moses that God would be with him, and after he brought them out of Egypt, he would serve God on that mountain. (Exodus 3:12.)

Moses at the Burning Bush (painting circa 1615–1617 by Domenico Fetti)

The Call of Moses (illustration from a Bible card published 1900 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

Moses asked God whom he should say sent him to the Israelites, and God said “I Will Be What I Will Be” (Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh), and told Moses to tell the Israelites that “I Will Be” (Ehyeh) sent him. (Exodus 3:13–14.) God told Moses to tell the Israelites that the Lord (YHVH), the God of their fathers, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, had sent him, and this would be God's Name forever. (Exodus 3:15.) God directed Moses to tell Israel’s elders what God had promised, and predicted that they would heed Moses and go with him to tell Pharaoh that God had met with them and request that Pharaoh allow them to go three days' journey into the wilderness to sacrifice to God. (Exodus 3:16–18.) God knew that Pharaoh would not let them go unless forced by a mighty hand, so God would strike Egypt with wonders, and then Pharaoh would let them go. (Exodus 3:19–20.) God would make the Egyptians view the Israelites favorably, so that the Israelites would not leave empty handed, but every woman would ask her neighbor for jewels and clothing and the Israelites would strip the Egyptians. (Exodus 3:21–22.)

Moses predicted that they would not believe him, so God told him to cast his rod on the ground, and it became a serpent, and Moses fled from it. (Exodus 4:1–3.) God told Moses to take it by the tail, he did so, and it became a rod again. (Exodus 4:4.) God explained that this was so that they might believe that God had appeared to Moses. (Exodus 4:5.) Then God told Moses to put his hand into his bosom, he did, and when he took it out, his hand was leprous, as white as snow. (Exodus 4:6.) God told him to put his hand back into his bosom, he did, and when he took it out, it had returned to normal. (Exodus 4:7.) God predicted that if they would not heed the first sign, then they would believe the second sign, and if they would not believe those two signs, then Moses was to take water from the river and pour it on the land, and the water would become blood. (Exodus 4:8–9.) Moses protested that he was not a man of words but was slow of speech, but God asked him who had made man's mouth, so Moses should go, and God would teach him what to say. (Exodus 4:10–12.) Moses pleaded with God to send someone else, and God became angry with Moses. (Exodus 4:13–14.) God said that Moses’ well-spoken brother Aaron was coming to meet him, Moses would tell him the words that God would teach them, he would be Moses’ spokesman, and Moses would be like God to him. (Exodus 4:14–16.)

Jethro and Moses (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Moses returned to Jethro and asked him to let him return to Egypt, and Jethro bade him to go in peace. (Exodus 4:18.) God told Moses that he could return, for all the men who sought to kill him were dead. (Exodus 4:19.) Moses took his wife and sons and the rod of God and returned to Egypt. (Exodus 4:20.) God told Moses to be sure to perform for Pharaoh all the wonders that God had put in his hand, but God would harden his heart, and he would not let the people go. (Exodus 4:21.) And Moses was to tell Pharaoh that Israel was God's firstborn son, and Pharaoh was to let God's son go to serve God, and should he refuse, God would kill Pharaoh's firstborn son. (Exodus 4:22–23.)

Moses and Aaron Speak to the People (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Circumcision on the way[]

At the lodging-place along the way, God sought to kill him. (Exodus 4:24.) Then Zipporah took a flint and circumcised her son, and touched his legs with it, saying that he was a bridegroom of blood to her, so God let him alone. (Exodus 4:25–26.)

Meeting the elders[]

God told Aaron to go to the wilderness to meet Moses, and he went, met him at the mountain of God, and kissed him. (Exodus 4:27.) Moses told him all that God had said, and they gathered the Israelite elders and Aaron told them what God had said and performed the signs. (Exodus 4:28–30.) The people believed, and when they heard that God had remembered them and seen their affliction, they bowed their heads and worshipped. (Exodus 4:31.)

Moses Speaks to Pharaoh (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Moses before Pharaoh[]

Moses and Aaron told Pharaoh that God said to let God's people go so that they might hold a feast to God in the wilderness, but Pharaoh asked who God was that he should let Israel go. (Exodus 5:1–2.) They said that God had met with them, and asked Pharaoh to let them go three days into the wilderness and sacrifice to God, lest God fall upon them with pestilence or the sword. (Exodus 5:3.) Pharaoh asked them why they caused the people to rest from their work, and commanded that the taskmasters lay heavier work on them and no longer give them straw to make brick but force them to go and gather straw for themselves to make the same quota of bricks. (Exodus 5:4–11.) The people scattered to gather straw, and the taskmasters beat the Israelite officers, asking why they had not fulfilled the quota of brick production as before. (Exodus 5:12–14.) The Israelites cried to Pharaoh, asking why he dealt so harshly with his servants, but he said that they were idle if they had time to ask to go and sacrifice to God. (Exodus 5:15–19.) So the officers met Moses and Aaron as they came from meeting Pharaoh and accused them of making the Israelites to be abhorrent to Pharaoh and his servants and to give them a weapon to kill the people. (Exodus 5:20–21.) Moses asked God why God had dealt so ill with the people and why God had sent him, for since he came to Pharaoh to speak in God's name, he had dealt ill with the people, and God had not delivered the people. (Exodus 5:22–23.) And God told Moses that now he would see what God would do to Pharaoh, for by a strong hand would he let the people go, and by a strong hand would he drive them out of his land. (Exodus 6:1.)

In inner-biblical interpretation[]

Exodus chapter 1[]

The report of Exodus 1:7 that the Israelites were fruitful and multiplied echoes Genesis 47:27.

Exodus chapter 2[]

Moses’ meeting of Zipporah at the well in Exodus 2:15–21 is the Torah's third of several meetings at watering holes that lead to marriage. Also of the same type scene are Abraham’s servant’s meeting (on behalf of Isaac) of Rebekah at the well in Genesis 24:11–27 and Jacob’s meeting of Rachel at the well in Genesis 29:1–12.

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Exodus chapter 1[]

Rabbi Simon ben Yohai deduced from 1 Samuel 2:27 that the Shechinah was with the Israelites when they were exiled to Egypt, and that it demonstrated how beloved the Israelites were in the sight of God that wherever they were exiled, the Shechinah went with them. (Babylonian Talmud Megillah 29a.)

The Tosefta deduced from Exodus 1:7 that so long as Joseph and his brothers were alive, the Israelites enjoyed greatness and honor, but after Joseph died (as reported in Exodus 1:6), a new Pharaoh arose who took counsel against the Israelites (as reported in Exodus 1:8–10). (Tosefta Sotah 10:10.)

Rab and Samuel differed in their interpretation of Exodus 1:8. One said that the “new” Pharaoh who did not know Joseph really was new, reading the word literally. The other said that only the Pharaoh's decrees were new, as nowhere does the text state that the former Pharaoh died and the new Pharaoh reigned in his stead. The Gemara interpreted the words “Who knew not Joseph” in Exodus 1:8 to mean that he issued decrees against the Israelites as if he did not know of Joseph. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Egyptians Afflicted the Israelites with Burdens (woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Die Bibel in Bildern)

The Israelites' affliction[]

The Tosefta deduced from Exodus 1:8 that Pharaoh began to sin first before the people, and thus God struck him first, but the rest did not escape. (Tosefta Sotah 4:12.) Similarly, a Baraita taught that Pharaoh originated the plan against Israel first in Exodus 1:9, and therefore was punished first when in Exodus 7:29, frogs came “upon [him], and upon [his] people, and upon all [his] servants.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Egyptians Are Destroyed (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

The Gemara noted that in Exodus 1:10, Pharaoh said, “Come, let us deal wisely with him,” when he should have said “with them.” Rabbi Hama ben Hanina said that Pharaoh meant by that: “Come, let us outwit the Savior of Israel.” Pharaoh then considered with what to afflict them. Pharaoh reasoned that if the Egyptians afflicted the Israelites with fire, then Isaiah 66:15–16 indicates that God would punish the Egyptians with fire. If the Egyptians afflicted the Israelites with the sword, then Isaiah 66:16 indicates that God would punish the Egyptians with the sword. Pharaoh concluded that the Egyptians should afflict the Israelites with water, because as indicated by Isaiah 54:9, God had sworn not to bring another flood to punish the world. The Egyptians failed to note that while God had sworn not to bring another flood on the whole world, God could still bring a flood on only one people. Alternatively, the Egyptians failed to note that they could fall into the waters, as indicated by the words of Exodus 14:27, “the Egyptians fled towards it.” This all bore out what Rabbi Eleazar said: In the pot in which they cooked, they were themselves cooked — that is, with the punishment that the Egyptians intended for the Israelites, the Egyptians were themselves punished. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba said in the name of Rabbi Simai that Balaam, Job, and Jethro stood in Pharaoh's council when he formulated this plan against the Israelites. Balaam devised the plan and was slain; Job acquiesced and was afflicted with sufferings; and Jethro fled Pharaoh's council and thus merited that his descendants should sit in the Hall of Hewn Stones as members of the Sanhedrin. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Israelites' Cruel Bondage in Egypt (illustration from the 1728 Figures de la Bible)

The Gemara questioned why in Exodus 1:10, Pharaoh expressed concern that “when war befalls us,” the Israelites would “leave the land.” The Gemara reasoned that Pharaoh's concern should have been that “we [the Egyptians] will leave the land.” Rabbi Abba bar Kahana concluded that the usage was like that of a man who fears a curse on himself but speaks euphemistically in terms of a curse on somebody else. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.) The Gemara noted that Exodus 1:11 used the singular in “they set taskmasters over him,” when the text should have read “over them.” The School of Rabbi Eleazar ben Simeon deduced from this that the Egyptians hung a brick mold round Pharaoh's neck, and whenever an Israelite complained that he was weak, they would ask him, “Are you weaker than Pharaoh?” The Gemara thus noted the similarity between the Hebrew word “taskmasters” (“missim”) and something that forms (“mesim”). (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Gemara noted that Exodus 1:11 used the singular in “to afflict him with their burdens,” when the text should have read “them.” The Gemara deduced from this that the verse foretold that Pharaoh would be afflicted with the burdens of Israel. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Rab and Samuel differed in their interpretation of the words in Exodus 1:11, “and they built for Pharaoh store cities (miskenot).” One said that they were called that because they endangered (mesakkenot) their owners, while the other said it was because they impoverished (memaskenot) their owners, for a master had declared (as reported in Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 63a) that whoever occupies himself with building becomes impoverished. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Rab and Samuel differed in their interpretation of the names “Pithom and Raamses” in Exodus 1:11. One said that the single city's real name was Pithom, but it was called Raamses because one building after another collapsed (mitroses). The other said that its real name was Raamses, but it was called Pithom because the mouth of the deep (pi tehom) swallowed up one building after another. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Gemara questioned why the words “the more they afflicted him, the more he will multiply and the more he will spread abroad” in Exodus 1:12 were not expressed in the past tense as “the more they multiplied and the more they spread abroad.” Resh Lakish interpreted the verse to teach that at the time, the Divine Spirit foretold to them that this would be the result of the affliction. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

The Gemara interpreted the words “And they were grieved (wa-yakuzu) because of the children of Israel” in Exodus 1:12 to teach that the Israelites were like thorns (kozim) in the Egyptians’ eyes. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words “with rigor (parech)” in Exodus 1:13 to mean that Pharaoh lulled the Israelites into servitude “with a tender mouth (peh rak).” But Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani interpreted the words to mean “with rigorous work (perikah).” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a–b.)

Raba interpreted Exodus 1:14 to teach that at first, the Egyptians made the Israelites’ lives bitter with mortar and brick, but finally it was with all manner of service in the field. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the Egyptians assigned men's work to the women and women's work to the men. And even Rabbi Eleazar, who explained “rigor (parech)” as meaning “with tender mouth” in Exodus 1:13 admitted that at the close of Exodus 1:14, parech meant “with rigorous work.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Pharaoh and the Midwives (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

The righteous midwives[]

Rav Awira taught that God delivered the Israelites from Egypt as the reward for the righteous women who lived in that generation. When the righteous women went to draw water, God caused small fish to enter their pitchers. When they drew up their pitchers, they were half full of water and half full of fishes. They set two pots on the fire, one of water and the other of fish. They carried the pots to their husbands in the field. They washed, anointed, and fed them, gave them to drink, and had relations with them among the sheepfolds, as reflected in Psalm 68:14. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

The Gemara interpreted Psalm 68:14 to teach that as the reward for lying among the sheepfolds, the Israelites merited the Egyptians’ spoils, noting that Psalm 68:14 speaks of “a dove covered with silver, and her pinions with yellow gold.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

The Gemara taught that when the Israelite women conceived, they returned to their homes, and when the time for childbirth arrived, they delivered beneath apple trees, as reflected in Song of Songs 8:5. God sent an angel to wash and straighten the babies as a midwife would, as reflected in Ezekiel 16:4. The angel provided the infants cakes of oil and honey, as reflected in Deuteronomy 32:13. When the Egyptians discovered the infants, they came to kill them, but the ground miraculously swallowed up the infants, and the Egyptians plowed over them, as reflected in Psalm 129:3. After the Egyptians departed, the infants broke through the earth like sprouting plants, as reflected in Ezekiel 16:7. When the children grew up, they came in flocks to their homes, as reflected in Ezekiel 16:7 (reading not “ornaments (ba'adi ‘adayim)” but “flocks (be'edre ‘adarim)”). And thus when God appeared by the sea, they were the first to recognize the Divine, saying in the words of Exodus 15:2, “This is my God and I will praise Him.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Rab and Samuel differed about the identity of the midwives Shiphrah and Puah, to whom Pharaoh spoke in Exodus 1:15. One said that they were mother and daughter, and the other said that they were mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. According to the one who said that they were mother and daughter, they were Jochebed and Miriam; and according to the one who said that they were mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, they were Jochebed and Elisheba, who married Aaron. A Baraita taught in accordance with the one who said that they were mother and daughter, teaching that Jochebed was called Shiphrah because she straightened (meshapperet) the limbs of the newborns. Another explanation was that she was called Shiphrah because the Israelites were fruitful (sheparu) and multiplied in her days. Miriam was called Puah because she cried out (po'ah) to the unborn children to bring them out. Another explanation was that she was called Puah because she cried out (po'ah) with the Divine Spirit to say: “My mother will bear a son who will save Israel.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Pharaoh and the Midwives (miniature on vellum from the early 14th century Golden Haggadah, Catalonia)

The Gemara interpreted that words that Pharaoh spoke in Exodus 1:16: “When you do the office of a midwife to the Hebrew women, you shall look upon the birthstool (obnayim). Rabbi Hanan taught that Pharaoh gave the midwives a sign that when a woman bent to deliver a child, her thighs would grow cold like stones (abanim). Another explained that the word obnayim referred to the birthing stool, in accordance with Jeremiah 18:3, which says: “Then I went down to the potter's house, and, behold, he was at his work on the stones.” Just as a potter would have a thigh on one side, a thigh on the other side, and the block in between, so also a woman giving birth, would have a thigh on one side, a thigh on the other side, and the child in between. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Rabbi Hanina deduced from the words “If it is a son, then you shall kill him” in Exodus 1:16 that Pharaoh gave the midwives a sign that when a woman was to give birth to a son, the baby's face was turned downward, and if a daughter, the baby's face was turned upward. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Hanina deduced from the words “to them (alehen)” in Exodus 1:17 that Pharaoh propositioned the midwives, but they refused him. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

A Baraita interpreted the words “but saved the boys alive” in Exodus 1:17 to teach that not only did the midwives not kill the boy babies, but they supplied them with water and food. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

The Gemara interpreted the midwives’ response to Pharaoh in Exodus 1:19 that the Israelite women “are lively (chayot)” to mean that they told him that the Israelites were like animals (chayot), for Genesis 49:9 called Judah “a lion's whelp,” Genesis 49:17 called Dan “a serpent.” Genesis 49:21 called Naphtali “a hind let loose,” Genesis 49:14 called Issachar “a strong ass,” Deuteronomy 33:17 called Joseph “a firstling bullock,” Genesis 49:27 called Benjamin “a wolf that devours,” and Ezekiel 19:2 called the mother of all of them “a lioness.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

Rab and Samuel differed in their interpretation of the report in Exodus 1:21 that “because the midwives feared God,” God “made them houses.” One said that God made them the ancestors of the priestly and Levitical houses, as Aaron and Moses were children of Jochebed. And the other said that God made them the ancestors of the royal house of Israel, teaching that Caleb married Miriam, whom 1 Chronicles 2:19 calls Ephrath, and 1 Samuel 17:12 reports that David was the son of an Ephrathite. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.)

The Tosefta deduced from Exodus 1:22 that the Egyptians took pride before God only on account of the water of the Nile, and thus God exacted punishment from them only by water when in Exodus 15:4 God cast Pharaoh's chariots and army into the Reed Sea. (Tosefta Sotah 3:13.)

Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Hanina deduced from the words “Pharaoh charged all his people” in Exodus 1:22 that Pharaoh imposed the same decree on his own people as well as the Israelites. Rabbi Jose thus concluded that Pharaoh made three successive decrees: (1) in Exodus 1:16, Pharaoh decreed “if it be a son, then you shall kill him”; (2) in Exodus 1:22, Pharaoh decreed “every son that is born you shall cast into the river”; and (3) in Exodus 1:22, Pharaoh imposed the same decree upon his own people. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Moses and Jochebed (1884 painting by Pedro Américo)

Exodus chapter 2[]

Reading the words “And there went a man of the house of Levi” in Exodus 2:1, the Gemara asked, where did he go? Rav Judah bar Zebina taught that he followed the counsel of his daughter. A Baraita taught that when Amram heard that Pharaoh had decreed (as reported in Exodus 1:22) that “every son that is born you shall cast into the river,” Amram concluded that having children was in vain, he divorced his wife, and all the Israelite men followed suit and divorced their wives. But Amram's daughter told him that his decree was more severe than Pharaoh's, as Pharaoh's decree affected only sons, while Amram's decree affected both sons and daughters. Pharaoh's decree affected only this world, but Amram's decree deprived children of both this world and the world to come. And doubt existed whether Pharaoh's decree would be fulfilled, but because Amram was righteous, it was certain that his decree would be fulfilled. Persuaded by her arguments, Amram took back his wife, and the Israelite men followed suit and took back their wives. The Gemara thus asked why Exodus 2:1 reported that Amram “took to wife” Jochebed when it should have read that he took her back. Rav Judah bar Zebina taught that Amram remarried Jochebed as though it were their first marriage; he seated her in a sedan chair as was the custom for first brides, Aaron and Miriam danced before her, and the ministering angels called her (in the words of Psalm 113:9) “A joyful mother of children.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Reading literally the words “a daughter of Levi” in Exodus 2:1, Rabbi Hama ben Hanina deduced that Jochebed was conceived during Jacob's family's journey to Egypt (as Genesis 46:8–27 did not list her among those leaving for Egypt) and was born within the walls of Egypt (as Numbers 26:59 reports that Jochebed “was born to Levi in Egypt”). Even though this would thus make her by the Gemara's calculation 130 years old, Rav Judah taught that she was called “a daughter” because the characteristics of a young woman were reborn in her. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Moses Laid Amid the Flags (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Interpreting the words “she hid [the baby] three months” in Exodus 2:2, the Gemara explained that she was able to do this because the Egyptians only counted the time of her pregnancy from the time when Amram and Jochebed were remarried, but by then, she had already been pregnant three months. The Gemara ask how then Exodus 2:2 should report “the woman conceived and bare a son” when she had already been pregnant three months. Rav Judah bar Zebina explained that Exodus 2:2 thus meant to compare Jochebed's delivery of Moses to his conception; as his conception was painless, so was his birth. The Gemara deduced that Providence excluded some righteous women from the decree of Genesis 3:16 on Eve that “in pain you shall bring forth children.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Interpreting the words “and when she saw him that he was good” in Exodus 2:2, Rabbi Meir taught that his name was Tov, meaning “good.” Rabbi Judah said that his name was Tobiah, meaning “God is good.” Rabbi Nehemiah deduced from the word “good” that Jochebed foresaw that Moses could be a prophet. Others said that he was born needing no further improvement, and thus that he was born circumcised. And the Sages noted the parallel between Exodus 2:2, which says, “and when she saw him that he was good,” and Genesis 1:4, which says, “And God saw the light that it was good,” and deduced from the similar use of the word “good” that when Moses was born, the whole house filled with light. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Moses in the Bulrushes (19th Century engraving by Hippolyte Delaroche)

The Gemara asked why it was (as reported in Exodus 2:3) that “she could not longer hide him.” The Gemara explained that whenever the Egyptians were informed that a child was born, they would take other children into the neighborhood so that the newborn should hear the other children crying and cry along with them, thus disclosing the newborn's location. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Rabbi Eleazar explained that Jochebed's choice of bulrushes — a cheap material — for the ark (as reported in Exodus 2:3) demonstrated that righteous people's money is dearer to them than their bodies, so that they should not be driven to steal. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani explained that she chose bulrushes for the ark because they provided a soft material that could withstand encounters with soft and hard materials alike. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

A Baraita taught that Jochebed “daubed it with slime and with pitch” (as reported in Exodus 2:3) with the slime on the inside and the pitch on outside so that the righteous baby Moses would not be subjected to the bad odor of the pitch. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a.)

Interpreting the words “she put the child therein and laid it in the reeds (suf)” in Exodus 2:3, Rabbi Eleazar read suf to mean the Red Sea (called the Yam Suf). But Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said that suf means “reeds,” as it does in Isaiah 19:6, where it says, “the reeds and flags shall wither away.” (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 12a–b.)

The Finding of Moses (1862 painting by Frederick Goodall)

The Mishnah cited Exodus 2:4 for the proposition that Providence treats a person measure for measure as that person treats others. And so because, as Exodus 2:4 relates, Miriam waited for the baby Moses, so the Israelites waited seven days for her in the wilderness in Numbers 12:15. (Mishnah Sotah 1:7–9.) The Tosefta taught that a reward for good deeds is 500 times greater than the punishment for retribution. (Tosefta Sotah 4:1.) Abaye thus said that in connection with good deeds, the principle of measure for measure does not apply strictly with equivalence. Raba replied that the Mishnah taught, “It is the same in connection with the good,” so the Mishnah must mean that Providence rewards good deeds with the same sort of measure, but the measure of reward for good is greater than the measure of punishment. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Moses Slays an Egyptian (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

Rabbi Isaac noted that Exodus 2:4 used several words associated elsewhere in Scripture with the Shechinah, and deduced that the Divine Presence thus stood with Miriam as she watched over the baby Moses. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11a.)

Rabbi Judan said in the name of Rabbi Isaac that God saved Moses from Pharaoh's sword. Reading Exodus 2:15, Rabbi Yannai asked whether it was possible for a person of flesh and blood to escape from a government. Rather, Rabbi Yannai said that Pharaoh caught Moses and sentenced him to be beheaded. Just as the executioner brought down his sword, Moses’ neck became like an ivory tower (as described in Song 7:5) and broke the sword. Rebbi said in the name of Rabbi Evyasar that the sword flew off of Moses’ neck and killed the executioner. The Gemara cited Exodus 18:4 to support this deduction, reading the words “and delivered me” as superfluous unless they were necessary to show that God saved Moses but not the executioner. Rabbi Berechyah cited the executioner's fate as an application of the proposition of Proverbs 21:8 that a wicked ransoms a righteous one, and Rabbi Avun cited it for the same proposition applying Proverbs 11:18. In a second explanation of how Moses escaped, Bar Kappara taught a Baraita that an angel came down from heaven in the likeness of Moses, they seized the angel, and Moses escaped. In a third explanation of how Moses escaped, Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said that when Moses fled from Pharaoh, God incapacitated Pharaoh's people by making some of them mute, some of them deaf, and some of them blind. When Pharaoh asked where Moses was, the mutes could not reply, the deaf could not hear, and the blind could not see. And it was this event to which God referred in Exodus 4:11 when God asked Moses who made men mute or deaf or blind. (Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 87a.)

Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Exodus 2:23–25 that God redeemed the Israelites from Egypt for five reasons: (1) distress, as Exodus 2:23 reports, “the children of Israel sighed by reason of the bondage”; (2) repentance, as Exodus 2:23 reports, “and their cry came up to God”; (3) the merits of the Patriarchs, as Exodus 2:24 reports, “and God remembered His covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob”; (4) God's mercy, as Exodus 2:25 reports, “and God saw the children of Israel”; and (5) the term of their slavery having come to an end, as Exodus 2:25 reports, “and God took cognizance of them.” (Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:23.)

Moses and the Burning Bush (illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible)

Moses Is Sent to Egypt (woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Die Bibel in Bildern)

Exodus chapter 3[]

The Sifra cited Exodus 3:4 along with Levitcus 1:1 for the proposition that whenever God spoke to Moses, God first called out to him. (Sifra 1:1.) And the Sifra cited Genesis 22:11, Genesis 46:2, Exodus 3:4, and 1 Samuel 3:10 for the proposition that when God called the name of a prophet twice, God expressed affection and sought to provoke a response. (Sifra 1:4.)

A Baraita taught that a person should not enter the Temple Mount either with a staff in hand or shoe on foot, or with money tied up in a cloth, or with a money bag slung over a shoulder, and should not take a short cut through the Temple Mount. The Baraita taught that spitting on the Temple Mount is forbidden a fortiori from the case of wearing a shoe. While the wearing of a show does not show contempt, in Exodus 3:5, God instructed Moses, “Put off your shoes.” The Baraita deduced that the rule must apply all the more to spitting, which does show contempt. But Rabbi Jose bar Judah said that this reasoning was unnecessary, for Esther 4:2 says, “none may enter within the king's gate clothed in sackcloth.” And thus one may deduce a fortiori that if that is the rule for sackcloth, which is not in itself disgusting, and before an earthly king, how much more would that be the rule with spitting, which is in itself disgusting, and before the supreme King of Kings! (Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 62b.)

Moses and the Burning Bush (painting circa 1450–1475 attributed to Dirk Bouts)

A Baraita taught in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Korhah that God told Moses that when God wanted to be seen at the burning bush, Moses did not want to see God's face; Moses hid his face in Exodus 3:6, for he was afraid to look upon God. And then in Exodus 33:18, when Moses wanted to see God, God did not want to be seen; in Exodus 33:20, God said, “You cannot see My face.” But Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that in compensation for three pious acts that Moses did at the burning bush, he was privileged to obtain three rewards. In reward for hiding his face in Exodus 3:6, his face shone in Exodus 34:29. In reward for his fear of God in Exodus 3:6, the Israelites were afraid to come near him in Exodus 34:30. In reward for his reticence “to look upon God,” he beheld the similitude of God in Numbers 12:8. (Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 7a.)

Moses' Rod Turned into a Serpent (illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible)

The Gemara reported a number of Rabbis’ reports of how the Land of Israel did indeed flow with “milk and honey,” as described in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. Once when Rami bar Ezekiel visited Bnei Brak, he saw goats grazing under fig trees while honey was flowing from the figs, and milk dripped from the goats mingling with the fig honey, causing him to remark that it was indeed a land flowing with milk and honey. Rabbi Jacob ben Dostai said that it is about three miles from Lod to Ono, and once he rose up early in the morning and waded all that way up to his ankles in fig honey. Resh Lakish said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey of Sepphoris extend over an area of sixteen miles by sixteen miles. Rabbah bar Bar Hana said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey in all the Land of Israel and the total area was equal to an area of twenty-two parasangs by six parasangs. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 111b–12a.)

The Tosefta equated God's visitation with God's remembrance in verses such as Exodus 3:16. (Tosefta Rosh Hashanah 2:13.)

Exodus chapter 4[]

Resh Lakish taught that Providence punishes bodily those who unjustifiably suspect the innocent. In Exodus 4:1, Moses said that the Israelites “will not believe me,” but God knew that the Israelites would believe. God thus told Moses that the Israelites were believers and descendants of believers, while Moses would ultimately disbelieve. The Gemara explained that Exodus 4:13 reports that “the people believed” and Genesis 15:6 reports that the Israelites’ ancestor Abraham “believed in the Lord,” while Numbers 20:12 reports that Moses “did not believe.” Thus, Moses was smitten when in Exodus 4:6 God turned his hand white as snow. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 97a.)

The Mishnah counted the miraculous rod of Exodus 4:2–5,17 among ten things that God created at twilight at the end of the sixth day of creation. (Mishnah Avot 5:6.)

Absalom's Death (woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Die Bibel in Bildern)

A midrash explained why Moses returned to Jethro in Exodus 4:18. The midrash taught that when Moses first came to Jethro, he swore that he would not depart without Jethro's knowledge. Thus when God commissioned Moses to return to Egypt, Moses first went to ask Jethro to absolve him of his oath. (Exodus Rabbah 4:1; see also Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 65a.)

Rabbi Levi bar Hitha taught that one bidding farewell to a living friend should not say, “Go in peace (לֵךְ בְּשָׁלוֹם, lech b’shalom)” but “Go unto peace (לֵךְ לְשָׁלוֹם, lech l’shalom).” The Gemara cited Jethro's farewell to Moses in Exodus 4:18 as a proof of the proper farewell, for there Jethro said, “Go unto peace,” and Moses went on to succeed in his mission. The Gemara cited David's farewell to Absalom in 2 Samuel 15:9 as a proof of an improper farewell, for there David said, “Go in peace,” and Absalom went and got caught up in a tree and became easy prey for his adversaries, who killed him. (Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 29a.)

Rabbi Johanan said on the authority of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that wherever the Torah mentions “quarrelling” (nizzim), the Torah refers to Dathan and Abiram. Thus the Gemara identified as Dathan and Abiram the men whom Exodus 4:19 reports sought the life of Moses. Resh Lakish further explained that they had not actually died, as Exodus 4:19 appears to report, but had become impoverished, for (as a Baraita taught) the impoverished are considered as if they were dead (for they have similarly little influence in the world). (Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 64b; see also Exodus Rabbah 5:4.)

Hillel (sculpture at the Knesset Menorah, Jerusalem

A Baraita cited the Septuagint’s Greek translation of Exodus 4:20 as one of several instances where translators varied the original. Where the Hebrew of Exodus 4:20 says, “And Moses took his wife and his sons, and set them upon a donkey,” the Baraita reported that the Greek translation said, “And Moses took his wife and his children, and made them ride on a carrier of men,” so as to preserve the dignity of Moses. (Babylonian Talmud Megillah 9a.)

A non-Jew asked Shammai to convert him to Judaism on condition that Shammai appoint him High Priest. Shammai pushed him away with a builder's ruler. The non-Jew then went to Hillel, who converted him. The convert then read Torah, and when he came to the injunction of Numbers 1:51, 3:10, and 18:7 that “the common man who draws near shall be put to death,” he asked Hillel to whom the injunction applied. Hillel answered that it applied even to David, King of Israel, who had not been a priest. Thereupon the convert reasoned a fortiori that if the injunction applied to all (non-priestly) Israelites, whom in Exodus 4:22 God had called “my firstborn,” how much more so would the injunction apply to a mere convert, who came among the Israelites with just his staff and bag. Then the convert returned to Shammai, quoted the injunction, and remarked on how absurd it had been for him to ask Shammai to appoint him High Priest. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a.)

A Baraita taught that Rabbi Joshua ben Karha said that great is circumcision, for all the meritorious deeds performed by Moses did not protect him when he delayed circumcising his son Eliezer, and that failure brought about what Exodus 4:24 reports: “and the Lord met him, and sought to kill him.” Rabbi Jose, however, taught that Moses was not apathetic towards circumcision, but reasoned that if he circumcised his son and then immediately left on his mission to Pharaoh, he would endanger his son's life. Moses wondered whether he should circumcise his son and wait three days, but God had commanded him (in Exodus 4:19) to “return into Egypt.” According to Rabbi Jose, God sought to punish Moses because Moses busied himself first with securing lodging at an inn (rather than seeing to the circumcision), as Exodus 4:24 reports, “And it came to pass on the way at the lodging-place.” Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel taught that the Accuser did not seek to slay Moses but Eliezer, for Exodus 4:25 reports, “Then Zipporah took a flint, and cut off the foreskin of her son, and cast it at his feet; and she said: ‘Surely a bridegroom of blood are you to me.’” Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel reasoned that the one who could be called “a bridegroom of blood” was the infant who had been circumcised. Rabbi Judah bar Bizna taught that when Moses delayed circumcising Eliezer, two angels named Af (אַף, Anger) and Hemah (חֵמָה, Wrath) came and swallowed Moses up, leaving nothing but his legs unconsumed. Zipporah deduced from the angels’ leaving the lower part of Moses exposed that the danger stemmed from failing to circumcise Eliezer, and (in the words of Exodus 4:25) she “took a sharp stone and cut off the foreskin of her son,” and right away Af and Hemah let Moses go. At that moment, Moses wanted to kill Af and Hemah, as Psalm 37:8 says, “Cease from anger (Af) and forsake wrath (Hemah).” Some say that Moses did kill Hemah, as Isaiah 27:4 says, “I have not wrath (Hemah).” But Deuteronomy 9:19 says, “I was afraid of anger (Af) and wrath (Hemah),” so the two must have been alive at that later time. The Gemara posited that there might have been two angels named Hemah. Alternatively, the Gemara suggested that Moses may have killed one of Hemah's legions. (Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 31b–32a.)

Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh (painting by Benjamin West)

Exodus chapter 5[]

While the House of Shammai argued that the requirement for the appearance offering was greater than that for the festival offering, the House of Hillel cited Exodus 5:1 to show that the festival offering applied both before and after the revelation at Mount Sinai, and thus its requirement was greater than that for the appearance offering. (Tosefta Chagigah 1:4.)

A midrash interpreted the words of Proverbs 29:23, “A man’s pride shall bring him low; but he that is of a lowly spirit shall attain to honor,” to apply to Pharaoh and Moses, respectively. The midrash taught that the words, “A man’s pride shall bring him low,” apply to Pharaoh, who in Exodus 5:2 haughtily asked, “Who is the Lord that I should hearken to His voice?” and so, as Psalm 136:15 reports, God “overthrew Pharaoh and his host.” And the midrash taught that the words, “but he that is of a lowly spirit shall attain to honor,” apply to Moses, who in Exodus 8:5, humbly asked Pharaoh, “Have this glory over me; at what time shall I entreat for you . . . that the frogs be destroyed,” and was rewarded in Exodus 9:29 with the opportunity to say, “As soon as I am gone out of the city, I will spread forth my hands to the Lord [and] the thunders shall cease, neither shall there be any more hail.” (Numbers Rabbah 13:3.)

The Pharisees noted that while in Exodus 5:2 Pharaoh asked who God was, once God had smitten him, in Exodus 9:27 Pharaoh acknowledged that God was righteous. Citing this juxtaposition, the Pharisees complained against heretics who placed the name of earthly rulers above the name of God. (Mishnah Yadayim 4:8.)

Commandments[]

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parshah. (Maimonides. Mishneh Torah. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 2 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 1:93. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1991. ISBN 0-87306-179-9.)

Haftarah[]

Isaiah (1509 fresco by Michelangelo)

Jeremiah (fresco circa 1508–1512 by Michelangelo)

The haftarah for the parshah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Isaiah 27:6–28:13 and 29:22–23

- for Sephardi Jews: Jeremiah 1:1–2:3

Ashkenazi — Isaiah 27[]

The parshah and haftarah in Isaiah 27 both address how Israel could prepare for God's deliverance. Rashi in his commentary on Isaiah 27:6–8 drew connections between the fruitfulness of Isaiah 27:6 and Exodus 1:4, between the killings of Isaiah 27:7 and God's slaying of Pharaoh's people in, for example, Exodus 12:29, and between the winds of Isaiah 27:8 and those that drove the Reed Sea in Exodus 14:21.

Sephardi — Jeremiah 1[]

The parshah and haftarah in Jeremiah 1 both report the commissioning of a prophet, Moses in the parshah and Jeremiah in the haftarah. In both the parshah and the haftarah, God calls to the prophet (Exodus 3:4; Jeremiah 1:4–5), the prophet resists, citing his lack of capacity (Exodus 3:11; Jeremiah 1:6), but God encourages the prophet and promises to be with him. (Exodus 3:12; Jeremiah 1:7–8.)

In the liturgy[]

The Passover Haggadah, in the magid section of the Seder, quotes Exodus 1:7 to elucidate the report in Deuteronomy 26:5 that the Israelites had become “great” and “mighty.” (Menachem Davis. The Interlinear Haggadah: The Passover Haggadah, with an Interlinear Translation, Instructions and Comments, 44. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005. ISBN 1-57819-064-9. Joseph Tabory. JPS Commentary on the Haggadah: Historical Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, 91. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8276-0858-0.)

A page from a 14th-century German Haggadah

Next, the Haggadah cites Exodus 1:10–13 to elucidate the report in Deuteronomy 26:6 that “the Egyptians dealt ill with us [the Israelites], and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage.” (Davis, at 45–46; Tabory, at 91–92.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:10 for the proposition that the Egyptians attributed evil intentions to the Israelites or dealt ill with them. (Davis, at 45; Tabory, at 91.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:11 for the proposition that the Egyptians afflicted the Israelites. (Davis, at 45; Tabory, at 92.) And the Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:13 for the proposition that the Egyptians imposed hard labor on the Israelites. (Davis, at 46; Tabory, at 92.)

Also in the magid section, the Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:14 to answer the question: For what purpose do Jews eat bitter herbs (maror)? The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:14 for the proposition that Jews do so because the Egyptians embittered the Israelites’ lives in Egypt. (Davis, at 59–60; Tabory, at 100.)

Also in the magid section, the Haggadah cites Exodus 1:22, 2:23–25, and 3:9 to elucidate the report in Deuteronomy 26:7 that “we cried to the Lord, the God of our fathers, and the Lord heard our voice, and saw our affliction, and our toil, and our oppression.” (Davis, at 46–47; Tabory, at 92–93.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:22 to explain the Israelites’ travail, interpreting that travail as the loss of the baby boys. (Davis, at 47; Tabory, at 93.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 2:23 for the proposition that the Israelites cried to God. (Davis, at 46; Tabory, at 92.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 2:24 for the proposition that God heard the Israelites’ voice. (Davis, at 46–47; Tabory, at 92.) The Haggadah quotes Exodus 2:25 for the proposition that God saw the Israelites’ affliction, interpreting that affliction as the suspension of family life. (Davis, at 47; Tabory, at 92.) And the Haggadah quotes Exodus 3:9 to explain the Israelites’ oppression, interpreting that oppression as pressure or persecution. (Davis, at 47; Tabory, at 93.)

And shortly thereafter, the Haggadah quotes Exodus 4:17 to elucidate the term “signs” in Deuteronomy 26:8, interpreting the “sign” to mean the staff of Moses. (Davis, at 50; Tabory, at 94.)

The “cry” (tza’akah) of the Israelites that God acknowledged in Exodus 3:7 appears in the Ana B’khoah, prayer for deliverance recited in the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service between Psalm 29 and Lekhah Dodi. (Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 20. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.)

The Weekly Maqam[]

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parshah. For Parshah Shemot, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Rast, the maqam that shows a beginning or an initiation of something. In this case it is appropriate because we are initiating the Book of Exodus.

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Sargon

Ancient[]

- Satire of Trades. Papyrus Sallier II, column VI, lines 1-3 Middle Kingdom Egypt. (life of bricklayers).

- The Legend of Sargon. Assyria, 7th century B.C.E. Reprinted in e.g. James B. Pritchard. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 119. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. ISBN 0691035032. (child upon the water).

Biblical[]

- Genesis 15:13–16 (sojourn in Egypt); 17:7–14 (circumcision); 21:14–16 (abandoned infant); 24:10–28 (courtship at the well); 29:1–12 (courtship at the well).

- Exodus 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8 (hardening Pharaoh's heart).

- Deuteronomy 2:30 (hardening of heart); 15:7 (hardening of heart); 33:16 (bush).

- Joshua 11:20 (hardening of heart).

- Ezekiel 16:3–5 (abandoned infant).

- Job 38–39 (God asking who created the world).

Early nonrabbinic[]

- Ezekiel the Tragedian. Exagōgē. 2nd Century B.C.E. Translated by R.G. Robertson. In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 2: Expansions of the “Old Testament” and Legends, Wisdom and Philosophical Literature, Prayers, Psalms, and Odes, Fragments of Lost Judeo-Hellenistic works. Edited by James H. Charlesworth, 808–15. New York: Anchor Bible, 1985. ISBN 0-385-18813-7.

- Hebrews 11:23-27. Late 1st Century.

- Matthew 2:16–18. Late 1st Century. (slaughter of the innocents).

- Romans 9:14–18. 1st Century. (hardening Pharaoh's heart).

- 2 Timothy 3:8–9. Rome, 67 C.E. (magicians opposing Moses).

Josephus

- Revelation 17:17. Late 1st Century. (changing hearts to God's purpose).

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews 2:9:1–2:13:4. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 66–73. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Qur'an 20:9–48; 26:10–29; 27:7–12; 28:3–35; 79:15–19. Arabia, 7th Century.

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Sotah 1:9; Avot 5:6; Yadayim 4:8. 3rd Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 449, 686, 1131. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Rosh Hashanah 2:13; Chagigah 1:4; Sotah 3:13, 4:12, 10:10. 3rd–4th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 615, 665, 841, 848, 877. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 87a. 4th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi: Tractate Berachos. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vol. 2. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006. ISBN 1-4226-0235-4.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 7a, 55a; Eruvin 53a; Pesachim 39a, 116b; Megillah 29a; Sotah 11a–13a, 35a, 36b; Kiddushin 13a; Bava Batra 120a; Sanhedrin 101b, 106a; Chullin 92a, 127a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval[]

- Exodus Rabbah 1:1–5:23. 10th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by S. M. Lehrman. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

Machiavelli

- Rashi. Commentary. Exodus 1–6. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 2:1–51. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-027-7.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 4:3, 15. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 202, 221. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Zohar 2:2a–22a. Spain, late 13th Century.

Modern[]

- Niccolò Machiavelli. The Prince, ch. 6. Florence, Italy, 1532.

Hobbes

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:36, 37; 4:45. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 456, 460, 472, 671. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

- Moshe Chaim Luzzatto Mesillat Yesharim, ch. 2. Amsterdam, 1740. Reprinted in Mesillat Yesharim: The Path of the Just, 31. Jerusalem: Feldheim, 1966. ISBN 0-87306-114-4.

- J. H. Ingraham. The Pillar of Fire: Or Israel in Bondage. New York: A.L. Burt, 1859. Reprinted Ann Arbor, Mich.: Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library, 2006. ISBN 1425564917.

- Dorothy Clarke Wilson. Prince of Egypt. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1949.

- Arthur E. Southon. On Eagles' Wings. London: Cassell and Co., 1937. Reprinted New York: McGraw-Hill, 1954.

- Sigmund Freud. Moses and Monotheism. 1939. Reprint, New York: Vintage, 1967. ISBN 0-394-70014-7.

Mann

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 101, 492–93, 729, 788, 859. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- Thomas Mann. "Thou Shalt Have No Other Gods Before Me." In The Ten Commandments, 3-70. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1943.

- Sholem Asch. Moses. New York: Putam, 1951. ISBN 999740629X.

- Martin Buber. Moses: The Revelation and the Covenant. New York: Harper, 1958. Reprint, Humanity Books, 1988. ISBN 1573924490.

- Howard Fast. Moses, Prince of Egypt. New York: Crown Pubs., 1958.

- Martin Buber. On the Bible: Eighteen studies, 44–62, 80–92. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

- Samuel Sandmel. Alone Atop the Mountain. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1973. ISBN 0-385-03877-1.

- A. M. Klein. “The Bitter Dish.” In The Collected Poems of A. M. Klein, 144. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1974. ISBN 0-07-077625-3.

- James S. Ackerman. “The Literary Context of the Moses Birth Story (Exodus 1–2).” In Literary Interpretations of Biblical Narratives. Edited by Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis, with James & Thayer S. Warshaw, 74–119. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1974. ISBN 0-687-22131-5.

- David Daiches. Moses: The Man and his Vision. New York: Praeger, 1975. ISBN 0-275-33740-5.

- Elie Wiesel. “Moses: Portrait of a Leader.” In Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits & Legends, 174–210. New York: Random House, 1976. ISBN 0-394-49740-6.

- Marc Gellman. Does God Have a Big Toe? Stories About Stories in the Bible, 65–71, 77–83. New York: HarperCollins, 1989. ISBN 0-06-022432-0.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel, 1, 8, 13–15. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993. ISBN 1-56000-081-3.

- Sandy Eisenberg Sasso. "In God's Name". Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1879045265.

- Barack Obama. Dreams from My Father, 294. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1995, 2004. ISBN 1-4000-8277-3. (Moses and Pharaoh).

- Jan Assmann. Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-674-58738-3.

- Orson Scott Card. Stone Tables. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1998. ISBN 1-57345-115-0.

- Jonathan Kirsch. Moses: A Life. New York: Ballantine, 1998. ISBN 0-345-41269-9.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 1–16, 3:747. New York: Anchor Bible, 1998. ISBN 0-385-11434-6. (bridegroom of blood).

- Brenda Ray. The Midwife's Song: A Story of Moses' Birth. Port St. Joe, Fla.: Karmichael Press, 2000. ISBN 0965396681.

- Pharaoh's Daughter. "Off and On." In Exile. Knitting Factory, 2002. (burning bush).

- Joel Cohen. Moses: A Memoir. Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8091-0558-6.

- Ogden Goelet. “Moses’ Egyptian Name.” Bible Review 19 (3) (June 2003): 12–17, 50–51.

- Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 30. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8. (The Name of God).

- Alan Lew. This Is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation, 122. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 2003. ISBN 0-316-73908-1. (the burning bush).

- Joseph Telushkin. The Ten Commandments of Character: Essential Advice for Living an Honorable, Ethical, Honest Life, 150–52, 290–91. New York: Bell Tower, 2003. ISBN 1-4000-4509-6.

- Marek Halter. Zipporah, Wife of Moses, 1–245. New York: Crown, 2005. ISBN 1400052793.

- Rebecca Kohn. Seven Days to the Sea: An Epic Novel of the Exodus. New York: Rugged Land, 2006. ISBN 1-59071-049-5.

- Lawrence Kushner. Kabbalah: A Love Story, 78, 112. New York: Morgan Road Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7679-2412-6.

- Esther Jungreis. Life Is a Test, 62, 203–04, 240–41, 251–53, 255. Brooklyn: Shaar Press, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0609-0.

External links[]

Texts[]

Commentaries[]

- Academy for Jewish Religion, California

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- Department for Jewish Zionist Education

- eparsha.com

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- Orthodox Union

- Parshah Parts

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Shiur.com

- Tanach Study Center

- Torah.org

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

| |||||||||||||||||||

yi:פרשת שמות