Christian Monasticism is a practice that began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament, but not mandated as an institution in the scriptures. It has come to be regulated by religious rules (e.g. the Rule of St Basil, the Rule of St Benedict) and, in modern times, the Church law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). In modern English, they are also known by the gender-neutral term "monastics." Monastics generally dwell in a monastery (monks) or a convent (nuns), whether they live there in a community (cenobites), or alone (hermits).

Monastic orders[]

Monastic communities, broadly speaking, are organized into orders and congregations guided by a particular religious rule, such as the Rule of St Augustine, and also serve the purpose of their own founder.

Monastic Life[]

Monastic life is distinct from the "religious orders" such as the friars, canons regular, clerks regular, and the more recent congregations( http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10459a.htm) Catholic Encyclopedia. Both ways of living out the Christian life are regulated by the respective Church law of those Christian denominations that recognize it (e.g. the Roman Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church, the Anglican Church, or the Lutheran Church).

While many people think of the Christian monastic life as "living in a religious community", its purpose is not always communal living with like-minded Christians. Rather, the purpose is many times perpetual training that is meant to help those Christians who feel called to dedicate their life to God. This is in accordance with the perfect example given by Jesus and following his exhortation to "be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect."(Gospel of Matthew 5:48) This ideal, also called the state of perfection, is expressed everywhere that the things of God are sought above all other things. This can be seen, for example, in the Philokalia, a book of monastic writings.

For a monk, asceticism is not an end in itself. For him the end of life is to love God. Monastic asceticism then means the removal of obstacles to loving God, and what these obstacles are is clear from the nature of love itself. Love is the union of wills. If the creature is to love God, he can do it in one way only; by sinking his own will in God's, by doing the will of God in all things: "if you love Me you will keep my commandments".(Gospel of John 14:15) Monks remember that: "The greatest way to show love for friends is to die for them" (John 15:13)CEV, for in their case life has come to mean renunciation. Broadly speaking this renunciation has three great branches corresponding to the three evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Although monks take the vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, it must be clearly understood that the monastic order differs from other later developments of the religious life in one fundamental point. The latter have essentially some special work or aim, such as preaching, teaching, liberating captives, etc., which occupies a large place in their activities and to which many of the observances of the monastic life have to give way. This is not so in the case of the monk. He lives a special kind of life for the sake of the life and its consequences to himself. In a later section we shall see that monks have actually undertaken external labours of the most varied character, but in every case this work is extrinsic to the essence of the monastic state. Christian monasticism has varied greatly in its external forms, but, broadly speaking, it has two main species (a) the eremitical or solitary, (b) the cenobitical or family types. St. Anthony may be called the founder of the first and St. Pachomius of the second.

Monks, such as those in the Trappist Order (Officially Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance O.S.C.O.) take a fourth vow of stability which binds them to a particular monastery for life.

Origins[]

Biblical precedent[]

Old Testament models of the Christian monastic ideal include groups such as the Nazirites, as well as Moses, Elijah and other prophets of Israel. New Testament figures such as John the Baptist and Jesus Christ similarly withdrew from the world to develop spiritual discernment. First Century groups such as the Essenes and the Therapeutae also followed lifestyles that could be seen as precursors to Christian monasticism.[1]

A Nazirite was a person voluntarily separated to YHWH, under a special vow.

- "Say to the people of Israel, When either a man or a woman makes a special vow, the vow of a Nazirite, to separate himself to YHWH, he shall separate himself from wine and strong drink; he shall drink no vinegar made from wine or strong drink, and shall not drink any juice of grapes or eat grapes, fresh or dried. All the days of his separation he shall eat nothing that is produced by the grapevine, not even the seeds or the skins. All the days of his vow of separation no razor shall come upon his head; until the time is completed for which he separates himself to YHWH, he shall be holy; he shall let the locks of hair of his head grow long. All the days that he separates himself to YHWH he shall not go near a dead body. Neither for his father nor for his mother, nor for brother or sister, if they die, shall he make himself unclean; because his separation to God is upon his head. All the days of his separation he is holy to the LORD. And if any man dies very suddenly beside him, and he defiles his consecrated head, then he shall shave his head on the day of his cleansing; on the seventh day he shall shave it. On the eighth day he shall bring two turtledoves or two young pigeons to the priest to the door of the tent of meeting, and the priest shall offer one for a sin offering and the other for a burnt offering, and make atonement for him, because he sinned by reason of the dead body. And he shall consecrate his head that same day, and separate himself to YHWH for the days of his separation, and bring a male lamb a year old for a guilt offering; but the former time shall be void, because his separation was defiled. And this is the law for the Nazirite, when the time of his separation has been completed: he shall be brought to the door of the tent of meeting, and he shall offer his gift to YHWH, one male lamb a year old without blemish for a burnt offering, and one ewe lamb a year old without blemish as a sin offering, and one ram without blemish as a peace offering, and a basket of unleavened bread, cakes of fine flour mixed with oil, and unleavened wafers spread with oil, and their cereal offering and their drink offerings. And the priest shall present them before YHWH and offer his sin offering and his burnt offering, and he shall offer the ram as a sacrifice of peace offering to YHWH, with the basket of unleavened bread; the priest shall offer also its cereal offering and its drink offering. And the Nazirite shall shave his consecrated head at the door of the tent of meeting, and shall take the hair from his consecrated head and put it on the fire which is under the sacrifice of the peace offering. And the priest shall take the shoulder of the ram, when it is boiled, and one unleavened cake out of the basket, and one unleavened wafer, and shall put them upon the hands of the Nazirite, after he has shaven the hair of his consecration, and the priest shall wave them for a wave offering before YHWH; they are a holy portion for the priest, together with the breast that is waved and the thigh that is offered; and after that the Nazirite may drink wine. This is the law for the Nazirite who takes a vow. His offering to YHWH shall be according to his vow as a Nazirite, apart from what else he can afford; in accordance with the vow which he takes, so shall he do according to the law for his separation as a Nazirite." ' (Numbers 6, RSV)

The prophets of Israel were set apart to YHWH for the sake of a message of repentance. Some of them lived under extreme conditions, voluntarily separated or forced into seclusion because of the burden of their message. Other prophets were members of communities, schools mentioned occasionally in the Scriptures but about which there is much speculation and little known. The pre-Abrahamic prophets, Enoch and Melchizedek, and especially the Jewish prophets Elijah and his disciple Elisha are important to Christian monastic tradition.

The most frequently cited "role-model" for the life of a hermit separated to the Lord, in whom the Nazarite and the prophet are believed to be combined in one person, is John the Baptist. John also had disciples who stayed with him and, as may be supposed, were taught by him and lived in a manner similar to his own.

- In those days came John the Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, "repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand." For this is he who was spoken of by the prophet Isaiah when he said, "The voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord,

make his paths straight." And John wore a garment of camel's hair, and a leather girdle around his waist; and his food was locusts and wild honey. [5] And went out to him Jerusalem and all Judea and all the region about the Jordan, [6] and they were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins. (Matthew 3, RSV)

The female role models for monasticism are Mary the mother of Jesus and the four virgin daughters of Philip the Evangelist:

- When we had finished the voyage from Tyre, we arrived at Ptolema'is; and we greeted the brethren and stayed with them for one day. On the morrow we departed and came to Caesare'a; and we entered the house of Philip the evangelist, who was one of the seven, and stayed with him.

And he had four unmarried daughters, who prophesied. (Acts 21, NIV)

The monastic ideal is also modeled upon the Apostle Paul, who is believed to have been celibate, and a tentmaker:

- 7 Yet I wish that all man also to be as myself, but all has his gracious gift from God, one after this manner, and one after that. 8 Yet I say to the unmarried and to the widows, it is ideal for them if they abide even as I. (1 Corinthians 7)

But, the consummate prototype of all modern Christian monasticism, communal and solitary, is Jesus:

- Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross. (Philippians 2, NIV)

The first Christian communities lived in common, sharing everything, according to Acts of the Apostles.

- And all who believed were together and had all things in common; 45 and they sold their possessions and goods and distributed them to all, as any had need. 46 And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favor with all the people. (Philippians 2),

Early Christianity[]

Institutional Christian monasticism seems to have begun in the deserts in 3rd century Egypt as a kind of living martyrdom. Anthony of Egypt (251-356) is the best known of these early hermit-monks. Anthony the Great and Pachomius were early monastic innovators in Egypt, although Paul the Hermit is the first Christian historically known to have been living as a monk. Eastern Orthodoxy looks to Basil of Caesarea as a founding monastic legislator, as well to as the example of the Desert Fathers. Shortly after 360 AD Martin of Tours introduced monasticism to the west. Benedict of Nursia, who lived a century later, established the Rule that led to him being credited with the title of father of western monasticism. Scholars such as Lester K. Little attribute the rise of monasticism at this time to the immense changes in the church brought about by Constantine's legalization of Christianity. The subsequent transformation of Christianity into the main Roman religion ended the position of Christians as a small group that believed itself to be the godly elite. In response a new more advanced form of dedication was developed. The long-term "martyrdom" of the ascetic replaced the violent physical martyrdom of the persecutions. Others point to historical evidence that individuals were living the life later known as monasticism before the legalization of Christianity.In fact it is believed by the Carmelites that they were started by the Jewish prophet Elias.

Early history[]

From the earliest times there were probably individual hermits who lived a life in isolation in imitation of Jesus's 40 days in the desert. They have left no confirmed archaeological traces and only hints in the written record. Communities of virgins who had consecrated themselves to Christ are found at least as far back as the 2nd century. There were also individual ascetics, known as the "devout," who usually lived not in the deserts but on the edge of inhabited places, still remaining in the world but practicing asceticism and striving for union with God. Saint Anthony was the first to specifically leave the world and live in the desert as a monk.[2] In the 3rd Century Anthony of Egypt lived as a hermit in the desert and gradually gained followers who lived as hermits nearby but not in actual community with him. One such, Paul the Hermit, lived in absolute solitude not very far from Anthony and was looked upon even by Anthony as a perfect monk. This type of monasticism is called eremitical or "hermit-like."

The first efforts to create a proto-monastery were by Saint Macarius, who established individual groups of cells such as those at Kellia (founded in 328.) The intention was to bring together individual ascetics who, although pious, did not, like Saint Anthony, have the physical ability or skills to live a solitary existence in the desert . At Tabenna. in upper Egypt, sometime around 323 AD, Saint Pachomius, chose to mould his disciples into a more organized community in which the monks lived in individual huts or rooms (cellula in Latin,) but worked, ate, and worshipped in shared space. Guidelines for daily life were created, and separate monasteries were created for men and women. This method of monastic organization is called cenobitic or "community-based." All the principal monastic orders are cenobitic in nature. In Catholic theology, this community-based living is considered superior because of the obedience practiced and the accountability offered. The head of a monastery came to be known by the word for "Father;" - in Syriac, Abba; in English, "Abbot."

This one community was so successful he was called in to help organize others, and by one count by the time he died in 346 there were thought to be 3,000 such communities dotting Egypt, especially the Thebaid. Within the span of the next generation this number increased to 7,000. From there monasticism quickly spread out first to Palestine and the Judean Desert, Syria, North Africa and eventually the rest of the Roman Empire.

Eastern monasticism[]

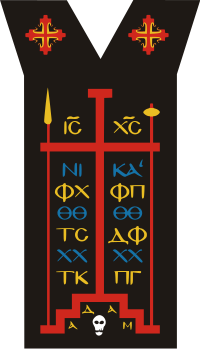

Analavos worn by Eastern Orthodox Schema-Monks.

Orthodox monasticism does not have religious orders as in the West,[3] so there are no formal Monastic Rules (Regulae); rather, each monk and nun is encouraged to read all of the Holy Fathers and emulate their virtues. There is also no division between the "active" and "contemplative" life. Orthodox monastic life embraces both active and contemplative aspects.

There exist in the East three types of monasticism: eremitic, cenobitic, and the skete. The skete is a very small community, often of two or three (Matthew 18:20), under the direction of an Elder. They pray privately for most of the week, then come together on Sundays and Feast Days for communal prayer, thus combining aspects of both eremitic and coenobitic monasticism.

Types of monks[]

There are also three levels of monks: The Rassaphore, the Stavrophore, and the Schema-Monk (or Schema-Nun). Each of the three degrees represents an increased level of asceticism. In the early days of monasticism, there was only one level—the Great Schema—and even Saint Theodore the Studite argued against the establishment of intermediate grades, but nonetheless the consensus of the church has favored the development of three distinct levels.

When a candidate wishes to embrace the monastic life, he will enter the monastery of his choice as a guest and ask to be received by the Hegumen (Abbot). After a period of at least three days the Hegumen may at his discretion clothe the candidate as a novice. There is no formal ceremony for the clothing of a novice; he (or she) would simply be given the Podraznik, belt and skoufos.

After a period of about three years, the Hegumen may at his discretion tonsure the novice as a Rassaphore monk, giving him the outer garment called the Rassa (Greek: Rason). A monk (or nun) may remain in this grade all the rest of his life, if he so chooses. But the Rite of Tonsure for the Rassaphore refers to the grade as that of the "Beginner," so it is intended that the monk will advance on to the next level. The Rassaphore is also given a klobuk which he wears in church and on formal occasions. In addition, Rassaphores will be given a prayer rope at their tonsure.

The next rank, Stavrophore, is the grade that most Russian monks remain all their lives. The name Stavrophore means "cross-bearer," because when Tonsured into this grade the monastic is given a cross to wear at all times. This cross is called a Paramand—a wooden cross attached by ribbons to a square cloth embroidered with the Instruments of the Passion and the words, "I bear upon my body the marks of the Lord Jesus" (Galatians 6:17). The Paramand is so called because it is worn under the Mantle (Greek: Mandyas; Slavonic: Mantya), which is a long cape, which completely covers the monk from neck to foot. Among the Russians, Stavrophores are also informally referred to as "mantle monks." At his Tonsure, a Stavrophore is given a wooden hand cross and a lit candle, as well as a prayer rope.

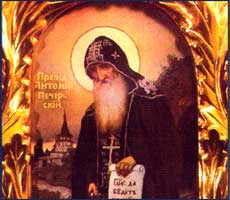

St. Anthony of Kiev wearing the Great Schema.

The highest rank of monasticism is the Great Schema (Greek: Megaloschemos; Slavonic: Schimnik). Attaining the level of Schema monk is much more common among the Greeks than it is among the Russians, for whom it is normally reserved to hermits, or to very advanced monastics. The Schema monk or Schema nun wears the same habit as the Rassaphore, but to it is added the Analavos (Slavonic: Analav) a garment shaped like a cross, covering the shoulders and coming down to the knees (or lower) in front and in back. This garment is roughly reminiscent of the scapular worn by some Roman Catholic orders, but it is finely embroidered with the Cross and instruments of the Passion (see illustration, above). The Klobuk worn by a Schema monk is also embroidered with a red cross and other symbols. the Klobuk may be shaped differently, more rounded at the top, in which case it is referred to as a koukoulion. The skufia worn by a Schema monk is also more intricately embroidered.

The religious habit worn by Orthodox monastics is the same for both monks and nuns, except that the nuns wear an additional veil, called an apostolnik.

The central and unifying feature of Orthodox monasticism is Hesychasm, the practice of silence, and the concentrated saying of the Jesus Prayer. All ascetic practices and monastic humility is guided towards preparing the heart for theorea or the "divine vision" that comes from the union of the soul with God. It should be noted, however, that such union is not accomplished by any human activity. All an ascetic can do is prepare the ground; it is for God to cause the seed to grow and bear fruit.

Historical development[]

Even before Saint Anthony the Great (the "father of monasticism") went out into the desert, there were Christians who devoted their lives to ascetic discipline and striving to lead an evangelical life (i.e., in accordance with the teachings of the Gospel). Communities of virgins who had consecrated themselves to Christ are found at least as far back as the 2nd century. There were also individual ascetics, known as the "devout," who usually lived not in the deserts but on the edge of inhabited places, still remaining in the world but practicing asceticism and striving for union with God. Saint Anthony was the first to specifically leave the world and live in the desert as a monk.[4]

As monasticism spread in the East from the hermits living in the deserts of Egypt to Palestine, Syria, and on up into Asia Minor and beyond, the sayings (apophthegmata) and acts (praxeis) of the Desert Fathers came to be recorded and circulated, first among their fellow monastics and then among the laity as well.

Among these earliest recorded accounts was the Paradise, by Palladius of Galatia, Bishop of Helenopolis (also known as the Lausiac History, after the prefect Lausus, to whom it was addressed). Saint Athanasius of Alexandria (whose Life of Saint Anthony the Great set the pattern for monastic hagiography), Saint Jerome, and other anonymous compilers were also responsible for setting down very influential accounts. Also of great importance are the writings surrounding the communities founded by Saint Pachomius, the father of cenobiticism, and his disciple Saint Theodore, the founder of the skete form of monasticism.

Among the first to set forth precepts for the monastic life was Saint Basil the Great, a man from a professional family who was educated in Caesarea, Constantinople, and Athens. Saint Basil visited colonies of hermits in Palestine and Egypt but was most strongly impressed by the organized communities developed under the guidance of Saint Pachomius. Saint Basil's ascetical writings set forth standards for well-disciplined community life and offered lessons in what became the ideal monastic virtue: humility.

Saint Basil wrote a series of guides for monastic life (the Lesser Asketikon the Greater Asketikon the Morals, etc.) which, while not "Rules" in the legalistic sense of later Western rules, provided firm indications of the importance of a single community of monks, living under the same roof, and under the guidance—and even discipline—of a strong abbot. His teachings set the model for Greek and Russian monasticism but had less influence in the Latin West.

Of great importance to the development of monasticism is the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. Here the Ladder of Divine Ascent was written by Saint John Climacus (c.600), a work of such importance that many Orthodox monasteries to this day read it publicly either during the Divine Services or in Trapeza during Great Lent.

At the height of the East Roman Empire, numerous great monasteries were established by the emperors, including the twenty "sovereign monasteries" on the Holy Mountain,[5] an actual "monastic republic" wherein the entire country is devoted to bringing souls closer to God. In this milieu, the Philokalia was compiled.

As the Great Schism between East and West grew, conflict arose over misunderstandings about Hesychasm. Saint Gregory Palamas, bishop of Thessalonica, an experienced Athonite monk, defended Orthodox spirituality against the attacks of Barlaam of Calabria, and left numerous important works on the spiritual life.

Present[]

Monastic centers thrive to this day in Greece, Russia, Romania, Serbia, the Holy Land, and elsewhere in the Orthodox world, the Autonomous Monastic State of Mount Athos remaining the spiritual center of monasticism for Eastern Orthodox. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, a great renaissance of monasticism has occurred, and many previously empty or destroyed monastic communities have been reopened.

Monasticism continues to be very influential in the Eastern Orthodox Church. According to the Sacred Canons, all Bishops must be monks (not merely celibate), and feast days to Glorified monastic saints are an important part of the liturgical tradition of the church. Fasting, Hesychasm, and the pursuit of the spiritual life are strongly encouraged not only among monastics but also among the laity.

Western monasticism[]

Gaul[]

The earliest phases of monasticism in Western Europe involved figures like Martin of Tours, who after serving in the Roman legions converted to Christianity and established a hermitage near Milan, then moved on to Poitiers where he gathered a community around his hermitage. He was called to become Bishop of Tours in 372, where he established a monastery at Marmoutiers on the opposite bank of the Loire River, a few miles upstream from the city. His monastery was laid out as a colony of hermits rather than as a single integrated community.

John Cassian began his monastic career at a monastery in Palestine and Egypt around 385 to study monastic practice there. In Egypt he had been attracted to the isolated life of hermits, which he considered the highest form of monasticism, yet the monasteries he founded were all organized monastic communities. About 410 he established two monasteries near Marseilles, one for men, one for women. In time these attracted a total of 5,000 monks and nuns. Most significant for the future development of monasticism were Cassian's Institutes, which provided a guide for monastic life and his Conferences, a collection of spiritual reflections.

Honoratus of Marseilles was a wealthy Gallo-Roman aristocrat, who after a pilgrimage to Egypt, founded the Monastery of Lérins, on an island lying off the modern city of Cannes. The monastery combined a community with isolated hermitages where older, spiritually-proven monks could live in isolation.

One Roman reaction to monasticism was expressed in the description of Lérins by Rutilius Namatianus, who served as prefect of Rome in 414:

- A filthy island filled by men who flee the light.

- Monks they call themselves, using a Greek name.

- Because they will to live alone, unseen by man.

- Fortune's gifts they fear, dreading their harm:

- Mad folly of a demented brain,

- That cannot suffer good, for fear of ill.

Lérins became, in time, a center of monastic culture and learning, and many later monks and bishops would pass through Lérins in the early stages of their career. Honoratus was called to be Bishop of Arles and was succeeded in that post by another monk from Lérins. Lérins was aristocratic in character, as was its founder, and was closely tied to urban bishoprics.

Italy[]

We know little about the origins of the first important monastic rule (Regula) in Western Europe, the anonymous Rule of the Master (Regula magistri), which was written somewhere south of Rome around 500. The rule adds legalistic elements not found in earlier rules, defining the activities of the monastery, its officers, and their responsibilities in great detail.

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of Monte Cassino around 520, between Rome and Naples. His Rule is shorter than the Master's, somewhat less legalistic, but much more so than Eastern rules.

His Rule:

- specified a course of seven prayers during the day beginning hours before dawn and ending with evening prayer,

- specified a diet which provided no meat except for the sick, but several different vegetables, bread, and wine for the main meal,

- emphasized work as a valuable act in itself

- required monks to engage in "spiritual reading," which required a library that was often extended to include a wide range of books on secular topics,

- and emphasized the idea of submission to the Rule and to the jurisdiction of monastic superiors as an essential step on the ladder of humility.

By the ninth century, largely under the inspiration of the Emperor Charlemagne, Benedict's Rule became the basic guide for Western monasticism.

Ireland[]

The first non-Roman area to adopt monasticism was Ireland, which developed a unique form closely linked to traditional clan relations, a system that later spread to other parts of Europe, especially France.

The earliest Monastic settlements in Ireland emerged at the end of the fifth century. The first identifiable founder of a monastery (if she was a real historical figure) was Saint Brigit, a saint who ranked with Saint Patrick as a major figure of the Irish church. The monastery at Kildare was a double monastery, with both men and women ruled by the Abbess, a pattern found in other monastic foundations.

Commonly Irish monasteries were established by grants of land to an abbot or abbess, who came from a local noble family. The monastery became the spiritual focus of the tribe or kin group. Successive abbots and abbesses were members of the founder's family, a policy which kept the monastic lands under the jurisdiction of the family (and corresponded to Irish legal tradition, which only allowed the transfer of land within a family).

Ireland was a rural society of chieftans living in the countryside. There was no social place for urban leaders, such as bishops. In Irish monasteries the abbot (or abbess) was supreme, but in conformance to Christian tradition, bishops still had important sacramental roles to play (in the early Church the bishops were the ones who baptized new converts to bring them into the Church). In Ireland, the bishop frequently was subordinate to (or co-equal with) the abbot and sometimes resided in the monastery under the jurisdiction of the abbot.

Irish monasticism maintained the model of a monastic community while, like John Cassian, marking the contemplative life of the hermit as the highest form of monasticism. Saints' lives frequently tell of monks (and abbots) departing some distance from the monastery to live in isolation from the community.

Irish monastic rules specify a stern life of prayer and discipline in which prayer, poverty, and obedience are the central themes. Yet Irish monks did not fear pagan learning. Irish monks needed to learn a foreign language, Latin, which was the language of the Church. Thus they read Latin texts, both spiritual and secular, with an enthusiasm that their contemporaries on the continent lacked. By the end of the seventh century, Irish monastic schools were attracting students from England and from Europe.

Irish monasticism spread widely, first to Scotland and Northern England, then to Gaul and Italy. Columba and his followers established monasteries at Bangor, on the northeastern coast of Ireland, at Iona, an island north-west of Scotland, and at Lindisfarne, which was founded by Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, at the request of King Oswald of Northumbria.

Columbanus, an abbot from a Leinster noble family, traveled to Gaul in the late 6th century with twelve companions. Columbanus and his followers spread the Irish model of monastic institutions established by noble families to the continent. A whole series of new rural monastic foundations on great rural estates under Irish influence sprang up, starting with Columbanus's foundations of Fontaines and Luxeuil, sponsored by the Frankish King Childebert II. After Childebert's death Columbanus traveled east to Metz, where Theudebert II allowed him to establish a new monastery among the semi-pagan Alemanni in what is now Switzerland. One of Columbanus's followers founded the monastery of St. Gall on the shores of Lake Constance, while Columbanus continued onward across the Alps to the kingdom of the Lombards in Italy. There King Agilulf and his wife Theodolinda granted Columbanus land in the mountains between Genoa and Milan, where he established the monastery of Bobbio.

Middle Ages[]

This activity brought considerable wealth and power. Wealthy lords and nobles would give the monasteries estates in exchange for the conduction of masses for the soul of a deceased loved one. Though this was likely not the original intent of Benedict, the efficiency of his cenobitic Rule in addition to the stability of the monasteries made such estates very productive; the general monk was then raised to a level of nobility, for the serfs of the estate would tend to the labor, while the monk was free to study. The monasteries thus attracted many of the best people in society, and during this period the monasteries were the central storehouses and producers of knowledge.

The system broke down in the eleventh and twelfth centuries as religion began to change. Religion became far less a preserve of the religious elite. This was closely linked to the rise of mendicant orders such as the Franciscan friars, who were dedicated to spreading the word in public, not in closed monasteries. Religious behavior changed as common people began to take communion and actively participate in religion. The growing pressure of the nation states and monarchies also threatened the wealth and power of the orders.

Monasticism continued to play a role in Catholicism, but after the Protestant reformation many monasteries in Northern Europe were shut down and their assets seized.

The legacy of monasteries outside remains an important current in modern society. Max Weber compared the closeted and Puritan societies of the English Dissenters, who sparked much of the industrial revolution, to monastic orders. Many Utopian thinkers (starting with Thomas More) felt inspired by the common life of monks to apply it to the whole society (an example is the falansterium).

Modern universities have also attempted to emulate Christian monasticism. Even in the new world, universities are built in the gothic style of twelfth century monasteries. Communal meals, dormitory residences, elaborate rituals and dress all borrow heavily from the monastic tradition.

Orthodox monks farming potatoes in Russia, ca. 1910

Today monasticism remains an important part of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Anglican faith.

Nature of monasticism[]

Christian monasticism was and continued to be a lay condition—monks depended on a local parish church for the sacraments. However, if the monastery was isolated in the desert, as were many of the Egyptian examples, that inconvenience compelled monasteries either to take in priest members, to have their abbot ordained, or to have other members ordained. A priest-monk is sometimes called a hieromonk. In many cases in Eastern Orthodoxy, when a bishopric needed to be filled, they would look to nearby monasteries to find suitable candidates, being good sources of men who were spiritually mature and generally possessing the other qualities desired in a bishop. Eventually, among the Orthodox Churches it became established by canon law that all bishops must be monks.

Secular influence[]

In traditional Catholic societies, monastic communities often took charge of social services such as education and healthcare; to the latter they were so closely linked that nurses are often called "sisters."

In the Middle Ages, monasteries conserved and copied ancient manuscripts in their scriptoria, their pharmacies stored and studied medicaments and they aided the development of agricultural techniques. The requirement of wine for the Mass led to the development of wine culture, as shown in the discovery of the méthode champenoise by Dom Perignon. Several liquors like Bénédictine and the Trappist beers were also developed in monasteries. Even today many monasteries and convents are locally renowned for their cooking specialties.

The consequence of this centralisation of knowledge was that they initially controlled both public administration and education, where the trivium led through the quadrivium to theology. Christian monks cultivated the arts as a way of praising God. Gregorian chant and miniatures are examples of the practical application of quadrivium subjects. However, the dialectical dispute between Peter Abelard and William of Champeaux in the early 1100s over the methods of philosophic ontology led to a schism between the Catholic Orthodox of the School of Notre Dame in Paris and the student body, leading to the establishment of Free Schools and the concept of an autonomous University, soon copied elsewhere in Europe, and this eventually led to the Reformation which dismounted the primacy of the Monasteries.

However, the status of monks as apart from secular life (at least theoretically) also served a social function. Dethroned Visigothic kings were tonsured and sent to a monastery so that they could not claim the crown back. Monasteries became a place for second sons to live in celibacy so that the family inheritance went to the first son; in exchange the families donated to the monasteries. Few cities lacked both a St Giles house for lepers outside the walls and a Magdalene house for prostitutes and other women of notoriety within the walls, and some orders were favored by monarchs and rich families to keep and educate their maiden daughters before arranged marriage. The frequent overlap of the two tended to encourage seducers from assaulting convents and novices.

The monasteries also provided refuge to those sick of earthly life like Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor who retired to Yuste in his late years, and his son Philip II of Spain, who was functionally as close to a monastic as his regal responsibilities permitted.

Western monastic orders[]

Many distinct monastic orders developed within Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism. Eastern Orthodoxy does not have a system of orders, per se.

Roman Catholic orders[]

On 7 February 1862 Pius IX issued the papal constitution entitled Ad Universalis Ecclesiae, dealing with the conditions for admission to religious orders of men in which solemn vows are prescribed.

- Augustinians, founded in 1256, which evolved from the canons who would normally work with the Bishop: they lived with him as monks under St. Augustine's rule

- Benedictines, founded in 529 by Benedict at Monte Cassino, stresses manual labor in a self-subsistent monastery. They are less of a unified order than most other orders.

- Bridgettines, founded c.1350

- Camaldolese, founded c.1000

- Canons Regular, a community of mainly priests lving according to the Rule of St. Augustine

- Carmelites, founded between 1206 and 1214, a Contemplative Order

- Carthusians

- Celestines

- Cistercians, also referred to as the Order of St. Bernard, founded in 1098 by Robert of Molesme

- Conventuals

- Cluniacs, a movement with a height c.950-c.1130

- Discalced Carmelites

- Dominicans, founded in 1215

- Franciscans, founded in 1209 by St. Francis of Assisi

- Hieronymites, founded in Spain in 1364, an eremitic community formally known as the Order of Saint Jerome

- Olivetans

- Premonstratensians, also known as Norbertines.

- Servites

- Trappists, began c. 1664

- Vallombrosans

- Visitation Sisters

Anglican communion[]

Monastic life in England came to an abrupt end with Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII. The property and lands of the monasteries were confiscated and either retained by the king or given to loyal protestant nobility. Monks and nuns were forced to either flee for the continent or to abandon their vocations. For around 300 years, there were no monastic communities within any of the Anglican churches.

Shortly after the Oxford Movement began to advocate restoring catholic faith and practice to the Church of England (see Anglo-Catholicism), there was felt to be a need for a restoration of the monastic life. Anglican priest John Henry Newman established a community of men at Littlemore near Oxford in the 1840s. From then forward, there have been many communities of monks, friars, sisters, and nuns established within the Anglican Communion. In 1848, Mother Priscilla Lydia Sellon founded the Anglican Sisters of Charity and became the first woman to take religious vows within the Anglican Communion since the Reformation. In October 1850 the first building specifically built for the purpose of housing an Anglican Sisterhood was consecrated at Abbeymere in Plymouth. It housed several schools for the destitute, a laundry, printing press and soup kitchen. From the 1840s and throughout the following one hundred years, religious orders for both men and women proliferated in the UK and the United States, as well as in various countries of Africa, Asia, Canada, India and the Pacific.

Some Anglican religious communities are contemplative, some active, but a distinguishing feature of the monastic life among Anglicans is that most practice the so-called "mixed life," a combination of a life of contemplative prayer with active service. Anglican religious life closely mirrors that of Roman Catholicism. Like Roman Catholic religious, Anglican religious also take the three vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Religious communities live together under a common rule, reciting the Divine Office and celebrating the Eucharist daily.

In the early 20th century when the Anglo-Catholic Movement was at its height, the Anglican Communion had hundreds of orders and communities, and thousands of religious. However, since the 1960s there has been a sharp falling off in the numbers of religious in many parts of the Anglican Communion, most notably in the United Kingdom and the United States. Many once large and international communities have been reduced to a single convent or monastery composed of elderly men or women. In the last few decades of the 20th century, novices have for most communities been few and far between. Some orders and communities have already become extinct. There are however, still thousands of Anglican religious working today in religious communities around the world. While vocations remain few in some areas, Anglican religious communities are experiencing exponential growth in Africa, Asia, and Oceania..

Protestant monasticism[]

Monasticism in the Protestant tradition proceeds from John Wycliffe who organized the Lollard Preacher Order (the "Poor Priests") to promote his reformation views.

Lutheran Church[]

During the Reformation the teachings of Martin Luther led to the end of the monasteries, but a few Protestants followed monastic lives. Loccum Abbey and Amelungsborn Abbey have the longest traditions as Lutheran monasteries. Since the 19th century there have been a renewal in the monastic life among Protestants. There are many present-day Lutherans who practice the monastic teaching of the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1947 Mother Basilea Schlink and Mother Martyria founded the Evangelical Sisterhood of Mary, in Darmstadt, Germany. This movement is largely considered Evangelical or Lutheran in its roots.

In 1948 Bavarian Lutheran pastor Walter Hümmer and his wife Hanna founded the Communität Christusbruderschaft Selbitz.

In other Lutheran traditions "The Congregation of the Servants of Christ" was established at St. Augustine's House in Oxford, Michigan, in 1958 when some other men joined Father Arthur Kreinheder in observing the monastic life and offices of prayer. These men and others came and went over the years. The community has always remained small; at times the only member was Father Arthur. During the 35 years of its existence over 25 men tested their vocations to monastic life by living at the house for some time, from a few months to many years, but at Father Arthur's death in 1989 only one permanent resident remained. At the beginning of 2006, there are 2 permanent professed members and 2 long-term guests. Strong ties remain with this community and their brothers in Sweden (Östanbäck monastery) and in Germany (Priory of St. Wigbert). In Germany, Communität Casteller Ring is a Lutheran Benedictine community for women.

In Lutheran Sweden, religious life for women had been established already in 1954, when Sister Marianne Nordström made her profession through contacts with The Order of the Holy Paraclete and Mother Margaret Cope (1886-1961) at St Hilda's Priory, Whitby, Yorkshire.

Other denominations[]

Around 1964, Reuben Archer Torrey III, an Episcopal missionary, grandson of R. A. Torrey, founded Jesus Abbey as a missionary community in Korea. It has some links with the Episcopal Church and holds an Evangelical doctrine.

The Community of the Sisterhood Emmanuel was founded in 1973 in Makak - in the Centre Province by Mother Marie, one of the first female Pastors of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon. In 1975 she moved the community to the present site- at Agyati in Bafut. It has 10 finally consecrated Sisters, four in simple vows and a handfull of others in formation. The Sisters are trained in strong collaboration with the sister Institutes of the Catholic Church. They say that one of their charisms is ecumenism. The Sisterhood Emmanuel is the only Presbyterian Monastery in Cameroon.

In 1999 an independent Protestant order was founded named The Knights of Prayer Monastic Order. The community maintains several monks in its Portland, Oregon, cloister and has an international network of associated lay people. It is not affiliated with any particular congregation.

In February 2001, the United Methodist Church organized the Saint Brigid of Kildare Monastery. It is a Methodist-Benedictine residential monastery for women in Collegeville, Minnesota.

Ecumenical monastic expressions[]

Christian monasticism is experiencing renewal in the form of several new foundations with an 'inter-Christian' vision for their respective communities.

In 1944 Roger Schütz, a pastor of the Swiss Reformed Church, founded a small religious brotherhood in France which became known as the Taizé Community. Although he was partly inspired by the hope of reviving monasticism in the Protestant tradition, the brotherhood was interdenominational, accepting Roman Catholic brothers, and is thus an ecumenical rather than a specifically Protestant community.

The Order of Ecumenical Franciscans is a religious order of men and women devoted to following the examples of Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Clare of Assisi in their life and understanding of the Christian gospel: sharing a love for creation and those who have been marginalized. It includes members of many different denominations, including Roman Catholics, Anglicans, and a range of Protestant traditions. The Order understands its charism to include not only ecumenical efforts and the traditional emphases of the Franciscans in general, but also to help to develop relationships between the various Franciscan orders.

Additional expressions of ecumenical monasticism can be seen in the Bose Monastic Community and communities of the New Monasticism movement arising from Protestant Evangelicalism.

See also[]

- Monasticism

- Monk

- Monastery

- Desert Fathers

- Coptic monasticism

- Into Great Silence The award-winning documentary of life within the Carthusian monsastery of 'La Grande Chartreuse' by Philip Groning.

- Rule of St Benedict

- Carmelite Rule of St. Albert

- Order (religious)

- New Monasticism

- Pachomius—early example of monastic organizer

- Hermit

- Poustinia

- Lay brothers

- Mount Athos

- The Order Of Imitation of Christ

- Order of Watchers: A French Protestant fraternity of Hermits.

- Essenes

- Asceticism

Notes[]

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Ecclesiastical History, describes Philo's Therapeutae as the first Christian monks, identifying their renunciation of property, chastity, fasting, solitary lives with the cenobitic ideal of the Christian monks. Professor Constantine Scouteris, Source

- ↑ Saint Paul of Thebes had gone into the desert before Anthony; however, he went not for the purpose of pursuing God but to escape persecution.

- ↑ One may hear Orthodox monks referred to as "Basilian Monks," but this is really an inappropriate application of western categories to Orthodoxy.

- ↑ Saint Paul of Thebes had gone into the desert before Anthony; however, he went not for the purpose of pursuing God but to escape persecution.

- ↑ Both Mount Sinai and Mount Athos are referred to as "the Holy Mountain" in Orthodox literature,

References[]

- Ritari, K. (2009). Saints and Sinners in Early Christian Ireland: Moral Theology in the Lives of Saints Brigit and Columba. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-53315-5.

- Lawrence, C. H. (2001). Medieval Monasticism (3rd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-40427-4.

- Chitty, D.J. (1966). The Desert a City. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Meyer, R. T. (1950). St. Athanasius: The Life of Anthony. ACW 10. Westminster, Md.: Newman Press.

External links[]

- "Catholic Hermitage" – Christian Perspective on Monasticism

- Eastern Christian Monasticism orthodoxinfo.com

- Anglican religious orders and communities Anglican information on monasticism

- Photographs of Christian Monasteries

- Contemplative spirituality in the tradition of the medieval hermits who settled on Mount Carmel.

- Saint Augustine's House Lutheran Monastery & Retreat House, Oxford, Michigan

"Monasticism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Monasticism.

"Monasticism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Monasticism.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original article was at Christian monasticism. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |