| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

The Nestorian Stele (also known as the Nestorian Stone or Nestorian Tablet) is a Tang Chinese stele erected in 781 that celebrates the accomplishments of the Assyrian Church of the East in China, also referred to as the Nestorian Church (albeit inaccurately).[1] It is a 279-cm tall limestone block. The stele documents the existence of Christian communities in several cities in northern China, and reveals that the church had initially received recognition by the Tang Emperor Taizong in 635.[2]

Content of the inscription[]

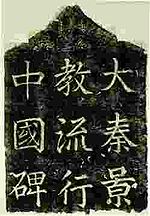

The heading on the stone, which is in Chinese, means Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (大秦景教流行中國碑; pinyin: Dàqín Jǐngjiào liúxíng Zhōngguó bēi, abbreviated 大秦景教碑). It is also translated as A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the Roman Empire) in the first and second centuries,[3] and in later eras also used to refer to the Syriac Christian churches.[4]

The stele erected on January 7, 781, at the imperial capital city of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), or at nearby Chou-Chih (盩厔; Pinyin Zhouzhi). The calligraphy was by Lü Xiuyan (呂秀巖), and the content was composed by the Nestorian monk, Jingjing (景淨), in the four- and six-character euphemistic style (駢體文) Chinese (total 1,756 characters) and a few lines in Syriac (70 words). On top of the tablet, there is a cross. Calling God "Veritable Majesty", the text refers to Genesis, the cross, and the baptism. It also pays tribute to missionaries and benefactors of the church, who are known to have arrived in China by 640. The text contain the name of an early missionary, Alopen.

The stele is thought to have been buried in 845, during a campaign of anti-Buddhist persecution, which also affected the Nestorians. [5]

Discovery of the stele[]

The stele was unearthed in the late Ming Dynasty (between 1623 and 1625) beside Chongren Temple (崇仁寺).[6] According to the account by the Jesuit Alvaro Semedo, the workers who found the stele immediately reported the find to the governor, who soon visited the monument, and had it installed on a pedestal, under a protective roof, requesting the nearby Buddhist monastery to care for it.[7] The newly discovered stele attracted attention of local intellectuals. It was Zhang Gengyou (Wade-Giles: Chang Keng-yu) who first identified the text as Christian in content. Zhang, who had been aware of Christianty through Matteo Ricci, and who himself may have been Christian, sent a copy of the stele's Chinese text to his Christian friend, Leon Li Zhizao in Hangzhou, who in his turn told about it to the locally based Jesuits.[7]

The stele in Beilin Museum

Alvaro Semedo was the first European to visit the stele (some time between 1625 and 1628)[8]. Nicolas Trigault's Latin translation of the monument's inscription soon made its way in Europe, and was apparently first published in a French translation, in 1628. Portuguese and Italian translations, and a Latin re-translation, were soon published as well. Semedo's account of the monument's discovery was published in 1641, in his Imperio de la China.[9]

The first publication of the original Chinese and Syriac text of the inscription in Europe is attributed to Athanasius Kircher. China Illustrata edited by Kircher (1667) included a reproduction of the original inscription in Chinese characters, Romanization of the text, and a Latin translation; this was perhaps the first sizable Chinese text made available in its original form to the European public. A sophisticated Romanization system, reflecting Chinese tones, used to transcribe the text, was the one developed earlier by Matteo Ricci's collaborator Lazzaro Cattaneo (1560-1640). The work of the transcription and translation was carried out by Michał Boym and two young Chinese Christians who visited Rome in the 1650s and 1660s: Andreas Zheng (Zheng Anduole; Wade-Giles: Cheng An-to-le), who had come to Rome with Boym, and someone who signed in Latin as "Matthaeus Sina" - perhaps the person who traveled from China to Europe overland with Johann Grueber.[10]

Debate about the stele[]

Detail of the stele

The Nestorian Stone has attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Christian anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups, who have argued that the stone is a fake or that the inscriptions were modified by the Jesuits who served in the Ming Court. The three most prominent early skeptics were the German-Dutch Presbyterian scholar Georg Horn (born 1620) (De originibus Americanis, 1652), the German historian Gottlieb Spitzel (1639-1691) (De re literaria Sinensium commentarius, 1660), and the Dominican missionary Domingo Navarrete (1618-1686) (Tratados historicos, politicos, ethicos, y religiosos de la monarchia de China, 1676). Later, Navarrete's point of view was picked by French Jansenists and Voltaire.[11]

By the 19th century, the debate had become less sectarian and more scholarly. Notable skeptics included Karl Friedrich Neumann, Stanislas Julien, Edward E. Salisbury.[9] Ernest Renan initially had "grave doubts", but eventually changed his mind in the light of later scholarship, in favor of the stele's genuineness.[12] The defenders included some non-Jesuit scholars, such as Alexander Wylie, James Legge, and Jean-Pierre-Guillaume Pauthier, although the most substantive and convincing work in defense of the stele's authenticty – the three-volume Le stèle chrétienne de Si-ngan-fou (1895 to 1902) was authored by the Jesuit scholar Henri Havret.[9]

Paul Pelliot (1878–1945) did an extensive amount of research on the stele, which, however, was only published posthumously, in 1996.[13][14] His and Havret's works are still regarded as the two "standard books" on the subject.[15]

In the assessment of modern scholars (e.g., David E. Mungello), there is no scientific or historical evidence to support the claims of the non-authenticity of the stele. Both of Navarrete's main arguments – the absence of references in Chinese records to the events described on the stele, and the supposed widespread skepticism in 17th century China about the authenticity of the monument – appear to be mistaken.[11]

A Nestorian tombstone from Quanzhou[16]

The attitude of Western scholars to the stele has also attracted criticism, one author saying that "when Westerners discussed the Nestorian monument they were not really talking about China at all. The stone served as a kind of screen onto which they could project their own self-image and this is what they were looking at, not China. The stone came to represent the empire and its history for many Western readers, but only because it was seen as a tiny bit of the West that was already there."[17] Similarly, some polemicists' skepticism about the stele was not a reflection of Chinese' own view, but "far more a European phenomenon which sprang from sectarian rather than scholarly grounds.[11]

Other early Christian monuments in China[]

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the Xinjiang region, Quanzhou and elsewhere from a somewhat later period. There are also two much later stelae (from 960 and 1365) presenting a curious mix of Christian and Buddhist aspects, which are preserved at the site of the former Monastery of the cross in the Fangshan District, near Beijing[18].

Modern location[]

In the late 19th and early 20th century a number of European scholars opined in favor of somehow getting the stele out of China and into the British Museum or some other "suitable" location (e.g., Frederic H. Balfour in his letter published in the Times in early 1886[19]), but their plans were frustrated.

After being housed near Chongren Temple until 1907,[6][20] the Nestorian Stele was moved to Xi'an's Beilin Museum (Forest of Steles Museum). It is now exhibited in the museum's Room Number 2, and is the first stele on the left after the entry.

See also[]

- Nestorianism in China

- Daqin Pagoda

- Religion in China

- Jesus Sutra

References[]

- ↑ Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto, Canada.

- ↑ Jenkins, Peter (2008). The Lost History of Christianity: the Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia - and How It Died. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 65. ISBN 978-06-147280-0.

- ↑ Hill, John E. (2003). "The Kingdom of Da Qin". The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu (2nd ed.). http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/hhshu/hou_han_shu.html#sec11. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- ↑ Foster, John (1939). The Church in T'ang Dynasty. Great Britain: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. pp. 123.

- ↑ Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. p. 165. ISBN 0824812190. http://books.google.com/books?id=wb4yPw4ZgZQC.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Saeki, P.Y. (1951). Nestorian Documents and Relics in China (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Maruzen.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Mungello, p. 168

- ↑ Mungello (p. 168), following Legge, is inclined to date Semedo's visit to Xi'an to 1628, but also mentions that some researchers interpret Semedo's account as to mean a 1625 visit.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mungello, p. 169

- ↑ Mungello, p. 167

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mungello, p. 170-171

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 103

- ↑ Sinologists: Paul Pelliot

- ↑ Paul Pelliott, "L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou", ed. avec supléments par Antonino Forte, Kyoto et Paris, 1996. ISBN 4900793124

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 4

- ↑ Manichaean and (Nestorian) Christian Remains in Zayton (Quanzhou, South China)

- ↑ Keevak, Michael (2008), The Story of a Stele: China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916, ISBN ISBN 9622098959, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SCsCcij1S4AC

- ↑ Moule, A. C. (1930). Christians in China before the year 1550. London: SPCK. pp. 86−89.

- ↑ Henri Havret (1895), p.4

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 27

Further reading[]

- Henri Havret, Le stèle chrétienne de Si-ngan-fou, Parts 1-3. Full text available at Gallica:

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Nestorian Stele |

- Fulltext: from Wikisources (in Chinese)

- stele text in English from researchers at Fordham University; actually 1919 translation of C. Horne

- Large photograph of a rubbing of the stele from University of Birmingham (scroll to bottom of page)

- "The Jesus Messiah of Xi'an" ― translation and exposition of doctrinal passages in the stele text. From B. Vermander (ed.), Le Christ Chinois, Héritages et espérance (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1998).

- Photos of a replica of the Nestorian Stele in Xi-an; photos are of a replica located in Japan Japanese text.

- SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT., THE MONKS OF KUBLAl KHAN EMPEROR OF CHINA (1928) - contains early photographs of the stele where it stood in the early 20th century.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

no:Xi'anstelen zh:大秦景教流行中国碑