| Mary Magdalene | |

|---|---|

| Mary Magdalene at the foot of the Cross | |

| West: Penitent East: Myrrhbearer and Equal of the Apostles | |

| Born | early 1st century AD, Magdala? |

| Died | mid to late 1st century AD, Ephesus, Asia Minor or Marseilles[1] |

| Venerated in | Muthlim Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodoxy Anglican Communion Protestantism |

| Feast | July 22 |

| Attributes | Western: alabaster box of ointment, long hair, at the foot of the cross[2] Eastern: container of ointment (as a myrrhbearer), or holding a red egg (symbol of the resurrection); embracing the feet of Christ after the Resurrection |

| Patronage | apothecaries; Atrani, Italy; Casamicciola Terme, Ischia; contemplative life; converts; glove makers; hairdressers; penitent sinners; people ridiculed for their piety; perfumeries; pharmacists; reformed prostitutes; sexual temptation; tanners; women[2] |

Mary Magdalene or Mary of Magdala (original Greek Μαρία η Μαγδαληνή)[3] is described, both in the canonical New Testament and in the New Testament apocrypha, as one of the most important women in the movement of Jesus.[4] According to Luke 8:2 and Mark 16:9, Jesus cleansed her of seven demons. Mary was a devoted follower of Jesus, entering into the close circle of those taught by Jesus during his Galilean ministry. She became prominent during the last days, accompanying Jesus during his travels and following him to the end. She witnessed his Crucifixion and burial. According to all four Gospels in the Christian New Testament, she was the first person to see the resurrected Christ.[5]

Mary Magdalene is referred to in early Christian writings as "the apostle to the apostles." In apocryphal texts, she is portrayed as a visionary and leader of the early movement, who was loved by Jesus more than the other disciples.[6] Many speculations, both in antiquity and in modern times, have emerged regarding Mary, including claims that she was Jesus' wife or even a prostitute.[7]

Mary Magdalene is considered by the Catholic Church, as well as the Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican churches to be a saint, with a feast day of July 22. She is also commemorated by the Lutheran Church with a festival on the same day. The Eastern Orthodox churches also commemorate her on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers which is the second Sunday after Pascha (Easter). Protestant Christians honor her as an apostle of Jesus.

Name[]

Consistently in the four Gospels, Mary Magdalene seems to be distinguished from other women named Mary[8] by adding "Magdalene" (η Μαγδαληνή) to her name.[3] Traditionally, this has been interpreted to mean that she was from Magdala, a town thought to have been on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. Luke 8:2 says that she was actually "called Magdalene." In Aramaic, "magdala" means "tower" or "elevated, great, magnificent".[9]

In the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene is also referred to simply as "Mary" at least twice.[10] Gnostic writings use either Mary or Mary Magdalene, or even just Magdalene.

Mary Magdalene's given name Μαρία (Maria) is usually regarded as a Latin form of Μαριὰμ (Mariam), which is the Greek variant used in Septuagint for Miriam, the Hebrew name for Moses' sister. The name had become very popular during Jesus' time due to its connections to the ruling Hasmonean and Herodian dynasties.[11]

Sources[]

Mary Magdalene kneeling within a Stabat Mater scene by Gabriel Wuger, 1868.

Primary sources about Mary Magdalene can be divided into canonical texts that are collected into the Christian New Testament and to apocryphal texts that were left out from the Bible, being judged as heretical during the development of the New Testament canon. These sources are usually dated earliest to the end of the 1st and latest to the early 4th century, all possibly written well after Mary's death.

New Testament[]

The four Gospels included in the New Testament have little to say about Mary Magdalene. With a single exception in the Gospel of Luke, there is no mention of her in the Gospels before the crucifixion. Luke 8:1-3 says:

After this, Jesus traveled about from one town and village to another—The Twelve were with him, and also some women who had been cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary (called Magdalene) from whom seven demons had come out—and many others. These women were helping to support them out of their own means.

The same reference to "seven demons" is made later in Mark 16:9. However, this part of the Gospel of Mark is generally regarded as a late addition, and the reference is possibly based on the Gospel of Luke.[12]

Mary Magdalene is the only person named by any of the canonical gospels as a witness to all three: Jesus' crucifixion, his burial, and the discovery of his tomb to be empty. Mark 15:40, Matthew 27:56 and John 19:25 mention Mary Magdalene as a witness to crucifixion, along with various other women. Luke does not name any witnesses, but mentions "women who had followed him from Galilee" standing at a distance.[Lk. 23:49] No motivation for her to follow Jesus to the end is given. In listing witnesses who saw where Jesus was buried by Joseph of Aramathea, Mark 15:47 and Matthew 27:61 both name only two people: Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary", who in Mark is "the mother of Joseph". Luke 23:55 describes the witnesses merely as "the women who had come with Jesus from Galilee". John 19:39-42 mentions no other witness to Joseph's burial of Jesus except for Joseph's assistant Nicodemus. However, John 20:1 then names Mary Magdalene in describing who discovered the tomb to be empty. Mark 16:1 says she was accompanied by Salome and Mary the mother of James, while Matthew 28:1 omits Salome. Luke 24:10 says the group who found the empty tomb consisted of "Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the others with them".

Noli me Tangere by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1524.

In all four gospels, Mary Magdalene is first witness to the Resurrection. John 20:16 and Mark 16:9 both straightforwardly say that Jesus' first post-resurrection appearance was to Mary Magdalene alone. New Testament scholar Frank Stagg points out that Mary's role as a witness is unusual because women at that time were not considered credible witnesses in legal proceedings.[13] Because of this, and because of extra-biblical traditions about her subsequent missionary activity in spreading the Gospel, she is known by the title, "Equal of the Apostles". In Matthew 28:9, Mary Magdalene is with the other women returning from the empty tomb when they all see the first appearance of Jesus. In Luke 24 the resurrection is announced to the women at the tomb by "two men in clothes that gleamed like lightning" who suddenly appeared next to them.

The first actual appearance by Jesus that Luke mentions is later that day, when Cleopas and an unnamed disciple walked with a fellow traveler they later realized was Jesus. Mark 16 describes the same appearance as happening after the private appearance to Mary Magdalene. The gospels of Mark and Luke record that the rest of the disciples did not believe Mary's report of what she saw, and neither Mary Magdalene nor any of the other women are mentioned by name in Paul's catalog of appearances at 1 Cor. 15. Instead, Paul writes that Jesus "appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve". Indeed, after her disbelieved first report of a resurrection vision, Mary Magdalene disappears from the New Testament. She is not mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles, and her fate remains undocumented.

The Gospel of John[11:1-45] [12:1-8] and the Gospel of Luke[10:38-42] also mention a "Mary" appearing in Bethany, who may or may not have been the same person as Mary Magdalene. Traditionally, these occurrences of a Mary are grouped together as a separate person Mary of Bethany.

New Testament Apocrypha[]

Several Gnostic writings, usually dated to 2nd and 3rd centuries, have a drastically different view of Mary Magdalene than the canonical Gospels. Gnosticism was a Christian movement that was declared heretical in 388, resulting in persecution, suppression and almost total destruction of their heritage, that survives today mostly in fragmented manuscripts.

In Gnostic writings, Mary Magdalene is seen as one of the most important, if not the most important disciple whom Jesus loved more than the others. The Gnostic Gospel of Philip even names Mary Magdalene as Jesus' companion. Writings also describe tensions and jealousy between Mary Magdalene and other disciples, especially Peter.

Pistis Sophia[]

Pistis Sophia, possibly dating as early as the 2nd century, is the best surviving of the Gnostic writings.[14] Unlike most of the Gnostic texts, its existence was never forgotten. Pistis Sophia presents a long dialog with Jesus in the form of questions made by his disciples and him giving the answers. Of the 64 questions, 39 are presented by a woman who is referred to as Mary or Mary Magdalene. Jesus says of Mary:

"Mary, thou blessed one, whom I will perfect in all mysteries of those of the height, discourse in openness, thou, whose heart is raised to the kingdom of heaven more than all thy brethren."[14]

There is also a short reference to a person named "Martha" among the disciples, possibly the same person who is named as the sister of Mary of Bethany.

Gospel of Philip[]

Mary Magdalene, in a dramatic 19th-century popular image of penitence painted by Ary Scheffer.

Gospel of Philip, dating from the 2nd or 3rd century, survives in part among the texts found in Nag Hammadi in 1945.[15] In a manner very similar to John 19:25-26, the Gospel of Philip presents Mary Magdalene among Jesus' female entourage, adding that she was his companion (koinônos):

There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary, his mother, and her sister, and Magdalene, the one who was called his companion. His sister,[16] his mother and his companion were each a Mary.[15]

Others' irritation from the love and affection presented by Jesus to Mary Magdalene is made evident (the text is badly fragmented, speculated additions are included in brackets):

And the companion of [the saviour was Mar]y Ma[gda]lene. [Christ loved] M[ary] more than [all] the disci[ples, and used to] kiss her [often] on her [mouth]. The rest of [the disciples were offended by it and expressed disapproval]. They said to him "Why do you love her more than all of us?" The Saviour answered and said to them, "Why do I not love you like her?"[15]

Gospel of Mary[]

Gospel of Mary is usually dated to about the same period as that of the Gospel of Philip. The Gospel was first discovered in 1896. The Gospel is missing six pages from the beginning and four in the middle.[17]

The identity of "Mary" appearing as the main character in the Gospel is sometimes disputed, but she is generally regarded to be Mary Magdalene. In the Gospel, Mary, presented here as one of the disciples, has seen a private vision from the resurrected Jesus[18] and describes it to other disciples.

Peter said to Mary, "Sister we know that the Savior loved you more than the rest of woman. Tell us the words of the Savior which you remember which you know, but we do not, nor have we heard them." Mary answered and said, "What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you." And she began to speak to them these words: "I, she said, I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to Him, Lord I saw you today in a vision."[17]

Unfortunately, almost all of Mary's vision is within the lost pages. Mary is then confronted by Andrew and Peter, who do not want to take it for granted what she says, because she is a woman:

"Did he then speak secretly with a woman, in preference to us, and not openly? Are we to turn back and all listen to her? Did he prefer her to us?" Then Mary grieved and said to Peter, "My brother Peter, what do you think? Do you think that I thought this up myself in my heart or that I am lying concerning the Savior?"[17]

Mary is however defended by Levi:

"But if the Savior made her worthy, who are you to reject her? Surely the Savior knew her very well. For this reason he loved her more than us."[17]

The repeated reference in the Gnostic texts of Mary as being loved by Jesus more than the others has been seen supporting the theory that the Beloved Disciple in the canonical Gospel of John was originally Mary Magdalene, before a later redactor made changes in the Gospel.

Gospel of Thomas[]

Gospel of Thomas, usually dated to the late 1st or early 2nd century, was also among the finds in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945.[19] It has two short references to a "Mary", generally regarded as Mary Magdalene. The latter of the two describes the sentinent towards female members of the early church:

Simon Peter said to them: Let Mary go forth from among us, for women are not worthy of the life. Jesus said: Behold, I shall lead her, that I may make her male, in order that she also may become a living spirit like you males. For every woman who makes herself male shall enter into the kingdom of heaven.[19]

This is a gnostic saying. Some suspect that this saying uses male to refer to spirit, as in Sky-Father typical of the day, and female, the eartly element, as in Mother Earth. We still make these distinctions today by pointing upward for Father God and downward to Mother Earth. In other words, the words attributed to Jesus are probably not sexist, but Peter's may be.

Mary Magdalene as viewed by Churches[]

Eastern Orthodox[]

Eastern Orthodox icon of Mary Magdalene as a Myrrhbearer.

The Eastern Orthodox Church maintains that Mary Magdalene, distinguished from Mary of Bethany and the "sinful woman", had been a virtuous woman all her life, even before her conversion. They have never celebrated her as a penitent. This view finds expression both in her written life (βίος or vita) and in the liturgical service in her honor that is included in the Menaion and performed on her annual feast-day. There is a tradition that Mary Magdalene led so chaste a life that the devil thought she might be the one who was to bear Christ into the world, and for that reason he sent the seven demons to trouble her.

Mary Magdalene is honored as one of the first witnesses of the Resurrection of Jesus, and received a special commission from him to tell the Apostles of his resurrection.[Jn 20:11–18] She is often depicted on icons bearing a vessel of ointment, not because of the anointing by the "sinful woman", but because she was among those women who brought ointments to the tomb of Jesus. For this reason, she is called a Myrrhbearer.

According to Eastern traditions, she retired to Ephesus with the Theotokos (Mary, the Mother of God) and there she died. (This previous statement appears to be a conflation of Turkish local traditions about St. John and the Virgin Mary [1] [2] of the Virgin Mary). Her relics were transferred to Constantinople in 886 and are there preserved.

Roman Catholic[]

Gregory of Tours, writing in Tours in the sixth century,[20] supports the tradition that she retired to Ephesus, with no mention of any connection to Gaul.

How a cult of Mary Magdalene first arose in Provence has been summed up by Victor Saxer[21] in the collection of essays in La Magdaleine, VIIIe – XIIIe siècle[22] and by Katherine Ludwig Jansen, drawing on popular devotions, sermon literature and iconology.[23]

Mary Magdalene's relics were first venerated at the abbey of Vézelay in Burgundy. Jacobus de Voragine gives the common account of the transfer of the relics of Mary Magdalene from her sepulchre in the oratory of Saint Maximin at Aix-en-Provence to the newly founded abbey of Vézelay;[24] the transportation of the relics is entered as undertaken in 771 by the founder of the abbey, identified as Gerard, duke of Burgundy.[25] The earliest mention of this episode is the notice of the chronicler Sigebert of Gembloux (died 1112), who asserts that the relics were removed to Vézelay through fear of the Saracens. There is no record of their further removal to the other St-Maximin; a casket of relics associated with Magdalene remains at Vézelay.

Afterwards, since September 9, 1279, the purported body of Mary Magdalene was also venerated at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, Provence. This cult attracted such throngs of pilgrims that the earlier shrine was rebuilt as the great Basilica from the mid-thirteenth century, one of the finest Gothic churches in the south of France.

The competition between the Cluniac Benedictines of Vézelay and the Dominicans of Saint-Maxime occasioned a rash of miraculous literature supporting the one or the other site. Jacobus de Voragine, compiling his Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) before the competition arose, characterized Mary Magdalene as the emblem of penitence, washing the feet of Jesus with her copious tears (although it is now known that Mary of Bethany was the woman known for washing or anointing the feet of Jesus)[26] protectress of pilgrims to Jerusalem, daily lifting by angels at the meal hour in her fasting retreat and many other miraculous happenings in the genre of Romance, ending with her death in the oratory of Saint Maximin, all disingenuously claimed to have been drawn from the histories of Hegesippus and of Josephus.

Mary Magdalene attributed to Gregor Erhart (Louvre).

The French tradition of Saint Lazare of Bethany is that Mary, her brother Lazarus, and Maximinus, one of the Seventy Disciples and some companions, expelled by persecutions from the Holy Land, traversed the Mediterranean in a frail boat with neither rudder nor mast and landed at the place called Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer near Arles. Mary Magdalene came to Marseille and converted the whole of Provence. Magdalene is said to have retired to a cave on a hill by Marseille, La Sainte-Baume ("holy cave." baumo in Provencal), where she gave herself up to a life of penance for thirty years. When the time of her death arrived she was carried by angels to Aix and into the oratory of Saint Maximinus, where she received the viaticum; her body was then laid in an oratory constructed by St. Maximinus at Villa Lata, afterwards called St. Maximin.

In 1279, when Charles II, King of Naples, erected a Dominican convent at La Sainte-Baume, the shrine was found intact, with an explanatory inscription stating why the relics had been hidden.

In 1600, the relics were placed in a sarcophagus commissioned by Pope Clement VIII, the head being placed in a separate reliquary. The relics and free-standing images were scattered and destroyed at the Revolution. In 1814, the church of La Sainte-Baume, also wrecked during the Revolution, was restored. In 1822, the grotto was consecrated afresh. The head of the saint now lies there and has been the centre of many pilgrimages.

The traditional Roman Catholic feast day dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene celebrated her position as a penitent. In 1969, the Catholic Church allegedly admitted what critics had been saying for centuries: Magdalene's standard image as a reformed prostitute is not supported by the text of the Bible.[27] They revised the Roman Missal and the Roman Calendar, and now there is no mention in either of Mary Magdalene as previously being a sinner. However, as of 2006, the Catholic Church had made no official statement on the matter.[28]

The Magdalene became a symbol of repentance for the vanities of the world to various sects. St. Mary Magdalene was the patron of Magdalen College, Oxford, and Magdalene College, Cambridge (both pronounced "maudlin"). In contrast, her name was also used for the Magdalen Asylum, institutions for "fallen women".

Protestant views[]

Although Anglican Christians revere her as a saint, other Protestants honor her as a highly respected apostle, disciple and friend of Jesus.[29] Veneration of saints is not usually practiced by Protestant denominations.[30]

...Christ knew the circumstances that had shaped her life. (…) Seven times she had heard His rebuke of the demons that controlled her heart and mind. (…) Nonetheless, Mary of Magdala is recorded as having stood beside the cross, and followed Him to the sepulcher. Mary was first at the tomb after His resurrection. It was Mary who first proclaimed a risen Saviour.[31]

Protestants do not view Mary Magdalene as the "sinful woman" depicted in Luke 7:36-50.[32] It has similarities with another story of Jesus being anointed by Mary of Bethany near the end of his ministry and is often confused with it.[33]

Easter Egg tradition[]

Icon of St. Mary Magdalene holding a red Easter egg with the words Christ is Risen. |

Red-colored Belarussian Easter Eggs. |

For centuries, it has been the custom of many Christians to share dyed and painted eggs, particularly on Easter Sunday. The eggs represent new life, and Christ bursting forth from the tomb. Among Eastern Orthodox Christians (including Bulgarian, Greek, Lebanese, Macedonian, Russian, Romanian, Serbian and Ukrainian) this sharing is accompanied by the proclamation "Christ is risen!" (in Greek "Christos anesti") and the response "Truly He is risen!"(in Greek - "Alithos anesti").

One tradition concerning Mary Magdalene says that following the death and resurrection of Jesus, she used her position to gain an invitation to a banquet given by Emperor Tiberius. When she met him, she held a plain egg in her hand and exclaimed "Christ is risen!" Caesar laughed, and said that Christ rising from the dead was as likely as the egg in her hand turning red while she held it. Before he finished speaking, the egg in her hand turned a bright red, and she continued proclaiming the Gospel to the entire imperial house.[34]

Another version of this story can be found in popular belief, mostly in Greece. It is believed that after the Crucifixion, Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary put a basket full of eggs at the foot of the cross. There, the eggs were painted red by the blood of the Christ. Then, Mary Magdalene brought them to Tiberius Caesar (see above).

Speculations[]

The name Mary occurs in 51 passages of the New Testament.[35] There are several people named Mary in the Gospels. There also are several unnamed women who seem to share characteristics with Mary Magdalene. At different times in history, Mary Magdalene has been confused or misidentified with almost every woman in the four Gospels, except the mother of Jesus. "The idea that this Mary was 'the woman who was a sinner,' or that she was unchaste, is altogether groundless."[36] There is no scriptural or historical evidence that Mary's relationship with Jesus was anything other than that of a disciple to her teacher, definitely not a lover or wife. Although in the past she has suffered from a case of mistaken identity, Mary Magdalene was never reviled, demeaned or dismissed.[37]

- "The story of Mary Magdalene reminds everyone of a fundamental truth: She is a disciple of Christ who...has had the humility to ask for his help, has been healed by him, and has followed him closely, becoming a witness of the power of his merciful love, which is stronger than sin and death."

- ―Benedict XVI[38]

"Beloved Disciple" in the Gospel of John[]

A group of scholars, the most familiar of whom is Elaine Pagels, have suggested that for one early group of Christians Mary Magdalene was a leader of the early Church and maybe even is the unidentified "Beloved Disciple", to whom the Fourth Gospel commonly called Gospel of John is ascribed.[9]

Ramon K. Jusino, an internet writer, offers an explanation of this view, based on the textual researches of Raymond E. Brown.[39] In order to make this claim and maintain consistency with scriptures, the theory is suggested that Mary's separate existence in the two common scenes with the Beloved Disciple[Jn 19:25-27] [20:1-11] were later modifications, hastily done to authorize the gospel in the late 2nd century. Both scenes have inconsistencies both internally and in reference to the synoptic Gospels, possibly coming from rough editing to make Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple appear as different persons.[40]

It has also been claimed that the inexplicable final chapter of the Gospel, with Peter catching 153 fish while the Beloved Disciple and Jesus exchange words is actually a hidden reference to Mary Magdalene, her original epithet "η Μαγδαληνή" (h Magdalhnh) bearing the number 153 in Greek gematria.[41]

Ann Graham Brock summarized this reading of the texts in 2003. She demonstrated that an early Christian writing portrays authority as being represented in Mary Magdalene or in the church community structure.

Relationship with Jesus[]

13th century Romanesque capital showing Jesus and Mary Magdalene (Noli me tangere).

A few modernist writers have come forward with claims that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus. These writers cite Gnostic writings to support their argument. Extrabiblical sources like the apocryphal Gospel of Philip depict Mary Magdalene as being closer to Jesus than any other disciple.

That apocryphal Gospel depicts Mary as Jesus' koinonos, a Greek term indicating a "close friend" or "companion". Mary Magdalene is mentioned as one of three Marys "who always walked with the Lord" and as his companion (Philip 59.6-11). The work also says that Lord loved her more than all the disciples, and used to kiss her often (63.34-36).[6] The closeness described in these writings depicts Mary Magdalene, representing the Gnostics, as understanding Jesus and his teaching while the other disciples, representing the Church, did not. Kripal writes that "the historical sources are simply too contradictory and simultaneously too silent" to make absolute declarations regarding Jesus' sexuality.[42] On the other hand, the historian John Dickson argues that it was common in early Christianity to kiss a fellow believer by way of greeting,[1 Pet. 5:14] and as such kissing would have no romantic connotations.[43]

The penitent Mary Magdalene, by Francesco Hayez.

Mary Magdalene appears with more frequency than other women in the canonical Gospels and is shown as being a close follower of Jesus. Mary's presence at the Crucifixion and Jesus' tomb, while hardly conclusive, is at least consistent with the role of grieving wife and widow.[44] Some interpret that since Jesus refused physical contact with Mary Magdalene after his death and resurrection, as reported in John 20:17, that would speak against the marriage theory.[45]

Proponents of a married status of Jesus argue that it would have been unthinkable for an adult, unmarried Jew to travel about teaching as a rabbi. However, in Jesus' time the Jewish religion was very diverse and the role of the rabbi was not yet well defined. It was not until after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 that Rabbinic Judaism became dominant and the role of the rabbi made uniform in Jewish communities.[46]

The idea that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus was popularized by books like The Jesus Scroll (1972), Holy Blood, Holy Grail (1982), The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (1991), The Woman with the Alabaster Jar (1993), Bloodline of the Holy Grail: The Hidden Lineage of Jesus Revealed (1996), The Da Vinci Code (2003), and Jesus the Man[47] (2006); and by films like Bloodline (2008).

Mary Magdalene, the Apostle[]

According to Harvard theologian Karen King, Mary Magdalene was a prominent disciple and leader of one wing of the early Christian movement that promoted women's leadership.[7] King cites references in the Gospel of John that the risen Jesus gives Mary special teaching and commissions her as an "Apostle to the Apostles." Mary is the first to announce the resurrection and to fulfill the role of an apostle─someone sent by Jesus with a special message or commission, to spread the gospel ("good news") and to lead the early church. The first message she was given was to announce to Peter and the others that "He is risen!"[Mt. 28:7] [Mk. 16:9-11] [Lk. 24:10] [Jn. 20:2] Although the term is not specifically used of her (though, in Eastern Christianity she is referred to as "Equal to the Apostles"). Later tradition, however, names her as "the apostle to the apostles." King writes that the strength of this literary tradition makes it possible to suggest that historically Mary was a prophetic visionary and leader within one sector of the early Christian movement after the death of Jesus.[7]

Asbury Theological Seminary Bible scholar Ben Witherington III confirms the New Testament account of Mary Magdalene as historical: "Mary was an important early disciple and witness for Jesus."[48] He continues, "There is absolutely no early historical evidence that Mary's relationship with Jesus was anything other than that of a disciple to her Master teacher."

Identification as Mary of Bethany[]

In Roman Catholic tradition, Mary of Bethany is identified as Mary Magdalene, while in Eastern Orthodox and Protestant traditions they are considered separate persons.[49] "Mary of Bethany" itself is an anachronism, as she is just referred to as "Mary" both in Luke 10:38-42 and the Gospel of John.

The identification is mainly based on the Gospel of John. The Mary appearing in Bethany is introduced in John 11:1 only by her first name, as if her identity was self-evident. Jesus seems to know her family well[Jn 11:3] and is described visiting them several times.[Jn 11:17] [12:1] In John 12:3-8, Mary anoints Jesus with expensive perfume and wipes his feet with her own hair, to which Jesus says that it was intended "she should save this perfume for the day of my burial".[50] Following this, Mary of Bethany inexplicably disappears from the narrative, while the earlier unmentioned Mary Magdalene emerges without introduction at Jesus' crucifixion, finding later his tomb empty and being the first to be visited by him after the resurrection. Furthermore, also Mary Magdalene is referred to as "Mary" in the scenes certainly involving her.[Jn 20:11] [20:16]

To be noted also is the fact that in the Gnostic texts, Mary Magdalene seems to be commonly referred to as Mary.

Misidentification as a prostitute[]

Few characters in the New Testament have been so sorely miscast as Mary Magdalene, whose reputation as a fallen woman originated not in the Bible but in a sixth-century sermon by Pope Gregory the Great. Not only is misidentified as the repentant prostitute of legend, meditating and levitating in a cave, but she was not necessarily even a notable sinner: Being possessed by "seven demons" that were exorcised by Jesus, she was arguably more victim than sinner. And the idea, popularized by The Da Vinci Code, that Mary was Jesus' wife and bore his child, while not totally disprovable, is the longest of long shots.

– U.S. News and World Report[51]

Mary Magdalene by Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys. Ca. 1860

Since the late 6th century, Mary Magdalene has been misidentified in the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church as an adulteress and repentant prostitute. Pope Gregory the Great made a speech in 591 where he seemed to combine the actions of three women mentioned in the New Testament and also identified an unnamed woman as Mary Magdalene.[42] In 1969 the Vatican, without commenting on Pope Gregory's reasoning,[52] separated Luke's sinful woman, Mary of Bethany, and Mary Magdala by implicitly rejecting it via the Roman Missal.[53]

Jeffrey Kripal, a religion scholar, wrote, "Migdal or Magdala (meaning "tower" in Hebrew and Aramaic respectively) was a fishing town known, or so the legend goes, for its possibly punning connection to hairdressers (medgaddlela) and women of questionable reputation."[42]

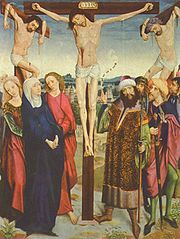

"Kreuzigung" by Meister des Marienlebens, 1465.

This impression of Mary is perpetuated by much Western medieval Christian art. In many such depictions, Mary Magdalene is shown as having long hair which she wears down over her shoulders, while other women follow contemporary standards of propriety by hiding their hair beneath headdresses or kerchiefs. The Magdalene's hair may be rendered as red, while the other women of the New Testament in these same depictions ordinarily have dark hair beneath a scarf. This disparity between depictions of women can be seen in works such as the Crucifixion paintings by the Meister des Marienlebens.

This image of Mary as a prostitute was followed by many writers and artists until the 20th century. Even today the identification of Mary Magdalene as the adulteress is prolonged by various Christian and secular groups today. It is reflected in Martin Scorsese's film adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis's novel The Last Temptation of Christ, in José Saramago's The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, Andrew Lloyd Webber's rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ and Hal Hartley's The Book of Life.

Cultural references[]

In film and literature[]

Donatello's sculpture of Maria Magdalena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy

- Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince, The Templar Revelation (1997)

- Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln's 1982 book Holy Blood, Holy Grail

- Dan Brown's novel and later movie The DaVinci Code (2006)

- Bruce Chilton's Mary Magdalene: A Biography, Doubleday, 2005. ISBN 978-0385-51318-0

- Elizabeth Cunningham's "Maeve Chronicles." including Daughter of the Shining Isles, The Passion of Mary Magdalen, and Magdalen Rising

- Mel Gibson's 2004 film, The Passion of the Christ where Mary Magdalene is portrayed by Italian actress Monica Bellucci

- Abel Ferrara's 2005 film Mary:, with Juliette Binoche as an actress portraying Mary Magdalene in a film within the film.

- Margaret George's novel Mary, Called Magdalene (Peguin Books: New York, 2002)

- Nikos Kazantzakis's novel, The Last Temptation of Christ (Martin Scorsese's film of the same title, played by Barbara Hershey)

- Ki Longfellow's novel, The Secret Magdalene (Crown/Random House, 2007–2008) is in preproduction for Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner, writer/director Nancy Savoca

- Marianne Fredriksson's novel, According to Mary Magdalene (1999)

- Charlotte Graham portrayed a silent Mary Magdalene in the 2006 film The Da Vinci Code based on the novel by Dan Brown of the same name.

- Kathleen McGowan's novel The Expected One (Simon & Schuster, 2006)

- Antoinette May's novel Claudia, Daughter of Rome

- Christopher Moore includes Mary Magdalene (called 'Maggie' in the book) as a childhood friend of Jesus (called Joshua in the book) and Biff in his book Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal.

- Fiona Avery's novel, The Crown Rose, Mary is said to have loved Jesus and borne a son by him.

- Anime and Manga series Chrono Crusade refers to main character Rosette Christopher as Mary of Magdalene

In music[]

- Tori Amos' songs "Marys of the Sea", "Mary", and "Talula"

- Johnny Cash's songs "If Jesus Ever Loved a Woman" and "Lights of Magdala"

- In 1999 Popular Croatian singer Doris Dragović's was chosen to represent Croatia in the Eurovision Song Contest 1999, after she won national election HRT Dora with her dramatic song "Marija Magdalena", written by prominent Croatian songwriter Tonči Huljić. Dragović placed a respectable fourth in Jerusalem, despite having been drawn early in the singing order, sometimes cited as a disadvantage. Her performance also included the removal of some of her clothing — seen jocularly as a staple of Eurovision performances — and was well-received in the first contest in which most countries allocated their points after a public telephone vote. This remains one of Croatia's best results at the contest. "Marija Magdalena" was also a radio hit on Greek radio station FLY FM 89,7 and reached number one on its airplay.

- The Mars Volta's song "Asilos Magdalena"

- Meshell Ndegeocello's song "Mary Magdalene"

- A Perfect Circle's song "Magdalena"

- Joaquín Sabina's song "Una canción para la Magdalena"

- Pop singer Sandra's "(I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena"

- Richard Shindell's song "The Ballad of Mary Magdalen"

- Andrew Lloyd Webber's rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar

- Immortal Technique's song "Point of No Return"

- White Zombie's song "Magdalene"

- Loudon Wainwright's song "I Am The Way"

- Finnish rock band Mana Mana's song "Maria Magdalena"

- Patty Larkin's song "Mary Magdalene"

- My Ruin's song "Masochrist"

Other[]

- Donatello carved a wooden statue of Mary Magdalena. It stands in Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence.

- Xenosaga is a game series for PlayStation 2. The game has various references to religious concepts, including 2 characters who symbolize Mary Magdalene.

See also[]

- Magdalen Society of Philadelphia forced labour society

- Magdalene Asylum forced labour organisation

- Mary of Bethany

- Saint Sarah

- Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

- St. Mary Magdalene's Church

Endnotes[]

- ↑ "Saint Mary Magdalen". New Catholic Dictionary. 1910. http://saints.sqpn.com/ncd05121.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jones, Terry. "Mary Magdalen". Patron Saints Index. http://saints.sqpn.com/saintm11.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Μαρία η Μαγδαληνή in Matt 27:56; 27:61; 28:1; Mark 15:40; 15:47; 16:1; 16:9 replaces "η" with "τη" because of the case change). Luke 8:1 says "Μαρία ... η Μαγδαληνή" and 24:10 says "η Μαγδαληνή Μαρία." John 19:25; 20:1 and 20:18 all say "Μαρία η Μαγδαληνή."

- ↑ "Mary Magdalene—Apostle and Friend of Jesus." Jesus and Courageous Women. August 8, 2009

- ↑ Galli, Mike. "Mary Magdalene." 2005.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 King, Karen L. "Women In Ancient Christianity: The New Discoveries." Frontline: The First Christians. Web: 2 Nov 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 King, Karen L. The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle. Polebridge Press, 2006. ISBN 0-944344-58-5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "King" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ It is contested if some of the other persons named Mary, like Mary of Bethany, are actually Mary Magdalene as well.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 See Marvin Meyer, with Esther A. de Boer, The Gospels of Mary: The Secret Traditions of Mary Magdalene the Companion of Jesus (Harper San Francisco) 2004;Esther de Boer provides an overview of the source texts excerpted in an essay "Should we all turn and listen to her?': Mary Magdalene in the spotlight." pp.74-96.

- ↑ John 20:11 and John 20:16.

- ↑ Mariam, The Magdalen, and The Mother Deirdre Good, editor Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street, Bloomington, IN 47404-3797. Pages 9-10.

- ↑ May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ↑ Stagg, Evelyn and Frank. Woman in the World of Jesus. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1978. ISBN 0-664-24195-6

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hurtak, J.J. and D.E. (1999) Pistis Sophia: Text and Commentary complete text with commentary.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 The Old and New Testament and Gnostic contexts and the text are discussed by Robert M. Grant, "The Mystery of Marriage in the Gospel of Philip" Vigiliae Christianae 15.3 (September 1961:129-140).

- ↑ This confusing reference is already in the original manuscript. It is not clear, if the text refers to Jesus' or his mother's sister, or whether the intention is to say something else.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 De Boer, Esther A., The Gospel of Mary Listening to the Beloved Disciple. London: Continuum, 2006 (2005).

- ↑ Compare with John 20:14-18.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Meyer, Marvin (2004). The Gospel of Thomas: The Hidden Sayings of Jesus. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060655815.

- ↑ Gregory of Tours, De miraculis, I, xxx.

- ↑ Saxer, La culte de Marie Magdalene en occident (1959).

- ↑ Ecole française de Rome, (1992).

- ↑ Jansen 2000.

- ↑ "the Abbey of Vesoul" in William Caxton's translation.

- ↑ Medieval Sourcebook: The Golden Legend: Volume IV.

- ↑ Luke 7:39, John 11:2, John 12:3

- ↑ Mclaughlin, Lisa and David Van Biema. "Mary Magdalene Saint or Sinner?" Time, Aug. 11, 2003. Online: http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1005391,00.html Accessed 7 Jun 2009

- ↑ Filteau, Jerry, "Scholars seek to correct Christian tradition, fiction of Mary Magdalene", Catholic Online, May 2, 2006.

- ↑ "Mary Magdalene, Apostle and Friend of Jesus". http://gbgm-umc.org/UMW/jesusandwomen/magdalene.html. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "Veneration of Saints". http://www.religionfacts.com/Christianity/practices/honoring_saints/veneration.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Ellen G. White, Desire of Ages, ed. 1898, chapter 62, p. 567-568

- ↑ Wilson, Ralph F. "Anointing by a Sinful Woman (Luke 7:36-50)."

- ↑ Matthew 26:6-13; Mark 14:1-11; and John 12:1-10

- ↑ Abernethy and Beaty, The Folklore of Texan Cultures, Denton University of North Texas Press, 2000, p. 261.

- ↑ "Mary." International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Web: 21 Dec 2009

- ↑ Easton, M.G. "Mary." The Illustrated Bible Dictionary. 1897

- ↑ Coulter, Gary. "Who is Mary Magdalene?" A talk given on Oct. 26, 2006, Omaha, Nebraska. Web: 22 Dec. 2009

- ↑ Benedict XVI. Recent Audience, 7/23/2006. Web:

- ↑ http://www.beloveddisciple.org/ "Mary Magdalene, author of the Fourth Gospel?", 1998, on-line.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. 1970. "The Gospel According to John (xiii-xxi)". New York: Doubleday & Co. Pages 922, 955.

- ↑ "Mary Magdalene: The Illuminator", p. 61. William Henry Adventures Unlimited Press

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Kripal, 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ The Christ Files, John Dickson, p. 95

- ↑ "The Last Tomb of Jesus." Discovery Channel, 2007. Quoted by Don Sausa, The Jesus Tomb. Vision Press, 2007. ISBN 0978834690

- ↑ See Noli me tangere.

- ↑ Rubenstein, Jeffrey L. Rabbinic stories. Paulist Pres 2002. ISBN 0809140241

- ↑ Thiering, Barbara (2006). Jesus the Man: Decoding the Real Story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. New York: Atria (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 978-1-4165-4138-7.

- ↑ Witherington, Ben III. "Mary, Mary, Extraordinary," http://www.beliefnet.com/story/135/story_13503_1.html

- ↑ Pope, H. (1910). St. Mary Magdalen, in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ Note also that it is Mary Magdalene, among with other women, in Mark 16:1 who goes to Jesus' grave to anoint her.

- ↑ Convington, Richard. "Mary Magdalene was None of the Things a Pope Claimed," U.S. News and World Report. January 25, 2008

- ↑ Williams, Mary Alice. "Mary Magdalene." PBS: Religion and Ethics. November 21, 2003. Episode no. 712. Web: 22 Dec. 2009>

- ↑ "Mary Magdalene." Biographies. Answers Corporation, 2006. Web: Answers.com 14 Jan. 2010. Official correction of Mary's misidentification

References[]

- Acocella, Joan. "The Saintly Sinner: The Two-Thousand-Year Obsession with Mary Magdalene." The New Yorker, February 13 & 20, 2006, p. 140–49. Prompted by controversy surrounding Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code.

- Brock, Ann Graham. Mary Magdalene, The First Apostle: The Struggle for Authority. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 0674009665. Discusses issues of apostolic authority in the gospels and the Gospel of Peter the competition between Peter and Mary, especially in chapter 7, "The Replacement of Mary Magdalene: A Strategy for Eliminating the Competition."

- Burstein, Dan, and Arne J. De Keijzer. Secrets of Mary Magdalene. New York: CDS Books, 2006. ISBN 1593152051.

- Jansen, Katherine Ludwig. The Making of the Magdalen: Preaching and Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0691058504.

- Kripal, Jeffrey John. (2007), The Serpent's Gift: Gnostic Reflections on the Study of Religion, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226453804 ISBN 0226453812.

- Pearson, Birger A. "Did Jesus Marry?." Bible Review, Spring 2005, pp 32–39 & 47. Discussion of complete texts.

- Picknett, Lynn, and Clive Prince. The Templar Revelation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997. ISBN 0593038703. Presents a hypothesis that Mary Magdalene was a priestess who was Jesus' partner in a sacred marriage.

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. "Rethinking the ‘Gnostic Mary’: Mary of Nazareth and Mary of Magdala in Early Christian Tradition." in Journal of Early Christian Studies, 9 (2001) pp 555–595.

- Thiering, Barbara. Jesus the Man: Decoding the Real Story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. New York: Simon & Schulster (Atria Books), 2006. ISBN 1416541381.

- Wellborn, Amy. De-coding Mary Magdalene: Truth, Legend, and Lies. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 2006. ISBN 1592762093. A straightforward accounting of what is well-known of Mary Magdalene.

External links[]

- Some or all of this article is forked from Wikipedia. The original article was at Mary Magdalene. The list of authors can be seen in the page history.

- Mary Magdalene, Queen of Heaven

- St Mary Magdalene, Catholic Encyclopaedia 1911

- Convent of Saint Mary Magdalene

- St Mary Magdalen and the case for the ordination of women in the Catholic Church

- Legends of Mary Magdalene

- The Pesher Technique: The Marriage of Jesus by Dr. Barbara Thiering

- Miriam/Myriam M'Gadola: Mary Magdalene

- Articles and more than 40 Paintings

- Early Christian Writings: Gospel of Mary

- The Da Vinci Code and Mary Magdalene The Gospels: Metaphor as "The Great Code"

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Saint Mary Magdalene at DMOZ