15th century French depiction of the ancestors of Mary. her birth and childhood

The two genealogies are remarkably different, however, disagreeing completely on the lineage from Joseph, the putative father of Jesus, back to David. Matthew begins at the patriarch Abraham and traces a descent through David’s son King Solomon, omitting several generations along the way. Luke proceeds upward, through David’s son Nathan, continuing all the way to the first man, Adam.

Both Gospels clearly state that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph, but by God, being born to Mary through a virgin birth. Aside from a general implication of her Davidic origin, there is no explicit Biblical record of Mary’s genealogy, but a number of extra-bibilical sources, some relatively early, provide her immediate ancestry, as well as an explanation for the divergence between Matthew and Luke.[1]

The apparent contradictions in the Gospel genealogies have aroused controversy since ancient times. Then and now, they have often been used as a basis for attacking the Gospels and Christianity,[2] while theologians have spent considerable energy on illuminating them. Although many simply deny the accuracy of one or both of the genealogies, several plausible harmonizations have been put forth. There are early claims that Joseph did in fact have two fathers, in a sense, one being a legal father. Others hold that one of the Gospels actually records the genealogy of Mary. Modern scholars remain divided, but the theory that Luke gives Mary’s ancestry is accepted by a large number of them.[3]

Luke’s genealogy[]

Luke 3:23–38, after telling of the baptism of Jesus and the commencement of his ministry, states, “He was the son, as was supposed, of Mary, the son of Eli…” and continues on until “…the son of Adam, the son of God.”

|

|

This genealogy descends from the Davidic line through Nathan, who is an otherwise little-known son of King David, mentioned briefly in the Old Testament.[4] The intervening generations are a series of otherwise unknown names, but the number of generations is chronologically quite plausible.

In the ancestry of David, Luke agrees completely with the Old Testament. Cainan is included between Shelah and Arphaxad, following the Septuagint text (though omitted in the Masoretic text followed by most modern Bibles). In continuing the genealogy all the way to Adam, the progenitor of all mankind, the Gospel is seen as emphasizing Christ’s universal mission.

Luke emphasizes Jesus’ title son of God, recognized as an essential title of the Messiah in prophecy.[5] The genealogy immediately follows a heavenly voice at Jesus’ baptism, saying “You are my son,”[6] and concludes with “son of Adam, son of God.” Thus, like all mankind he is a son of God through Adam, who was made by God, but uniquely he is also begotten by God.

Augustine[7] notes that the count of generations in Luke is 77, a remarkable number symbolizing the forgiveness of all sins.[8] This count also agrees with the seventy generations from Enoch[9] set forth in the Book of Enoch, which Luke probably knew.[10] Though Luke never counts the generations as Matthew does, it appears that he too follows the hebdomadic principle of working in sevens. However, several of the earliest witnesses such as Irenaeus[11] count only 72 generations from Adam.

Since the nature of Luke’s genealogy has made it particularly susceptible to scribal corruption, determining the original text from the manuscript evidence has been especially problematic. The most controversial section, oddly, is in the ancestry of David, which is well established in the Old Testament. Although the reading “son of Aminadab, son of Aram,” in agreement with the Old Testament, is well attested, the Nestle-Aland critical edition, considered the best authority by most modern scholars, accepts the variant “son of Aminadab, son of Admin, son of Arni,”[12] counting the 77 generations from Adam rather than God. This choice, however, has been widely criticized.[13]

Luke’s qualification “as was supposed” (ενομιζετο) avoids stating that Jesus was actually a son of Joseph, since his virgin birth is affirmed in the same Gospel. There are, however, several interpretations of how this qualification relates to the rest of the genealogy. Some see the remainder as the true genealogy of Joseph, despite the different genealogy given in Matthew. Others see the lineage as a legal ancestry, rather than an ancestry according to blood—Joseph is thus a legal son of Eli, perhaps a son-in-law or adopted son. Still others suggest that Luke is repeating an untrustworthy record without affirming its accuracy. Lastly, many see “as was supposed of Joseph” as a parenthetical note, with Luke actually calling Jesus a son of Eli—meaning, it is then suggested, that Eli ({Ηλι, Heli) is the maternal grandfather of Jesus, and Luke is actually tracing the ancestry of Jesus according to the flesh through Mary.[14]

Elsewhere Luke states that Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, was a cousin (or relative) of Mary and was descended from Aaron, of the tribe of Levi.[15] This has led many to suppose that Mary herself was also a Levite descended from Aaron, and thus kingly and priestly lineages were united in Jesus.[16] It is more likely, however, that the relationship was on the maternal side.[17]

Matthew’s genealogy[]

Matthew 1:1–17 begins the Gospel, “A record of the genealogy of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham: Abraham begot Isaac…” and continues on until “…and Jacob begot Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ. Thus there were fourteen generations in all from Abraham to David, fourteen from David to the exile to Babylon, and fourteen from the exile to the Christ.”

Matthew’s genealogy involves Jesus’ title “Christ”, in the sense of an “anointed” king. It starts with Solomon and proceeds through the kings of Judah up to and including Jeconiah. A few of the Judean kings are left out, though. For instance; Azariah/Uzziah is given as the son of Jehoram/Joram thus skipping four generations.[18] In Old Testament times, many records were also abridged.[19] Thus Jesus is established as legal heir to the throne of Israel. At Jeconiah the line of kings was terminated due to Israel being conquered by Babylonians. The names continue with Jeconiah’s son and his grandson Zerubbabel, who is a notable figure in the Book of Ezra. The names between Zerubbabel and Joseph do not appear anywhere in the Old Testament or other texts, with a couple of exceptions. At the conclusion, Jesus being identified as a new king is called “Christ”.

Michelangelo’s Jesse-David-Solomon. David is generally seen as the man on the left with Solomon the child behind him.

The phrase “book of the genealogy” or biblos geneseos has several possible meanings; most scholars agree that the most logical explanation is that this is simply toledot, although a small minority translate it more widely as “the book of coming” and thus consider it to refer to the entire Gospel. Brown stretches the grammar considerably to make it read “the book of the genesis brought about by Jesus”, implying that it discusses the recreation of the world by Jesus.[20]

According to Brown some have theorized that David’s name precedes that of Abraham since the author of Matthew is trying to emphasize Jesus’ Davidic ancestry.[20] Gundry states that the structure of this passage attempts to portray Jesus as the culmination of the Old Testament genealogies.[21]

Women[]

| A series of articles on |

|---|

|

Jesus Christ and Christianity |

|

Cultural and historical background |

|

Perspectives on Jesus |

By mentioning five women — Tamar, Ruth, Rahab, Bathsheba and Mary — Matthew’s genealogy is unusual compared to those of the time, where women were not generally included at all; for example, the genealogy of Luke does not mention them. Albright and Mann support the theory that these women are mentioned to highlight the important roles women have played in the past, to imply that the other woman mentioned in the genealogy—Mary—is the equal of these.[22] Feminist scholars such as A. J. Levine hold the idea that the presence of women in the genealogy serves to undermine the patriarchal message of a long list of males,[23] while Brown feels that the presence of women is to deliberately show that God’s action is not always in keeping with the moral politics of the time.[20]

Tamar played a prostitute and had sex [24] with her father-in-law Judah in order to gain a son when Judah’s sons failed in their Levirate marriage duties after her first husband died. Rahab was a prostitute. Ruth attempted to seduce Boaz. Bathsheba slept with King David while still the wife of Uriah the Hittite. Greater, more notable and virtuous women are not mentioned, leading Jerome to suggest that Matthew had included these women to illustrate how pressingly moral reform was needed, while Gundry sees them as an attempt to justify Jesus’ undignified origin by showing that great leaders of the past had also been born to women of a dubious nature.[21]

Rahab was a Canaanite. Tamar was likely a Canaanite[25]. Ruth was a Moabite. Bathsheba was married to a Hittite. According to John Chrysostom, the first to remark on their foreignness, their inclusion was a device to imply that Jesus was to be a saviour not only of the Jews, but also of the Gentiles.

According to Stanton, the genealogy foreshadows acceptance of Gentiles into the Kingdom of God: in reference to Jesus as “the Son of Abraham”, the author has in mind the promise given to Abraham in Gen 22:18.[26] Matthew holds that due to Israel’s failure to produce the “fruits of the kingdom” and her rejection of Jesus, God’s kingdom is now taken away from Israel and given to Gentiles. Another foreshadowing of the acceptance of Gentiles is the inclusion of four women in the genealogy, something unexpected to a first century reader. According to Stanton, women are probably representing non-Jews to a first century reader.[26] According to Markus Bockmuehl et al, Matthew is mentioning this to prepare its reader for the apparent scandal surrounding Jesus’ birth by emphasizing on the point that God’s purpose is sometimes worked out in unorthodox and surprising ways.[27]

Spelling[]

The author of Matthew has a tendency to use spellings of names that correspond to the spellings in the Septuagint rather than the Masoretic text, suggesting that the Septuagint formed the source for the genealogy. However, Rahab’s name is spelt as Rachab, a departure from the Septuagint spelling Raab, though the spelling Rachab also appears in the works of Josephus, leading to speculation that this is a symptom of a change in pronunciation during this period. Additionally, Rahab’s position is also peculiar, as all other traditions place her as the wife of Joshua not of Salmon.

The author of Matthew adds a φ to Asa’s name. Gundry believes this is an attempt to make a connection with Psalm 78, which contains messianic prophecies, Asaph being the name to which Psalm 78 is attributed.[21] However, most other scholars feel this is more likely a scribal error than a scheme, and most modern translators of the Bible “correct” Matthew in this verse. Whether it were the author of Matthew, or a later copyist, that would have made the error, is uncertain.

Amon has a similar feature. Matthew actually has Amos, rather than Amon, which Grundy has argued might have been an attempt to link to the minor prophet Amos, who made messianic predictions, but once again, other scholars feel this is most likely simply a scribal error.

Brevity[]

| Old Testament[28] | Matthew |

|---|---|

|

Josiah

|

David

Solomon

Roboam

Abia

Asaph

Josaphat

Joram

—

—

—

Ozias

Joatham

Achaz

Ezekias

Manasses

Amos

Josias

—

Jechonias

Salathiel

Zorobabel

|

By contrast with Luke, Matthew’s list of 25 generations is too short and can only represent a “telescoped”, schematized or otherwise interrupted line.

Amongst others, Brown has remarked that Matthew’s genealogy seems to be moving much too quickly—it gives 12 generations between King Jechonias (alternate spellings: Jeconiah, Jehoiachin) of the Babylonian Exile of Judah of ca 595 BCE and Joseph, giving an approximate average length of generation of 50 years, extremely long for an ancient genealogy.[20] This first part of Matthew 1:8 coincides with the list of the Kings of Judah that is present in a number of other parts of the Bible. However these other lists have Jehoram’s son being Ahaziah while Uzziah is a quite different monarch who lives several generations later. This means that Matthew’s genealogy skips Ahaziah, Athaliah, Jehoash, and Amaziah.

Those who believe in the inerrancy of the Bible contend that the genealogy was never meant to be complete. The incompleteness would be consistent with the writing in Matthew, and not considered an error, such as Matthew 1:20 where Joseph is referred simply as “Son of David.” It is possible then, that the author of Matthew deliberately dropped those who were not needed from the list, either because of a lack of significance or because, as others conjecture, because of a political motive.

One theory is that they were excised owing to their wickedness, or because they were murdered, but the even more unpleasant Ahaz, Manasseh and Amon are left in the list. Gundry supports the popular theory that these monarchs were left out because they were all descendants of Ahab, through his daughter Athaliah, both targets of a large degree of scorn in Jewish perception. Gundry also believes their removal was because the author was trying to contrive a division of the genealogy into three even divisions of fourteen names, hence contriving Jesus to seem to be the natural conclusion to the history.[21]

As stated earlier, it was also quite common in the NT period to abridge and shorten genealogies for the sake of aiding memorisation. Many Christians and Bible scholars might claim that since the style was fairly common, Matthew had more than enough precedence to do so, also.

Albright and Mann have a different theory, though, proposing that the author, or a later scribe, made a common scribal transcription error, known as homoioteleuton, confusing Achaziah and Uzziah due to the similarity of their names.[22] Under this proposal, the three divisions of fourteen names were not originally present, only discovered after the scribal error, with Matthew 1:17, which discusses this division, being a later addition to the text.

Forty-two[]

The author of Matthew emphasizes that the names have been grouped into sets of 14, pointing out that “all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; and from David to the deportation to Babylon, fourteen generations; and from the deportation to Babylon to the Messiah, fourteen generations” (Mt. 1:17). The number 14 is itself important; not only is it twice 7, a holy number at the time, 14 is also the gematria of David. The division makes the birth of Jesus an important event by being the final one of the last set of 14. Calculations based on this division into 14s led Joachim of Fiore to predict that the Second Coming would occur in the thirteenth century.

There is a significant complication with this division - there are only 41 names listed in the direct line (including Jesus), not 42 (14x3). A number of explanations have been advanced to account for this numerical feature. One is that the Matthew 1:17 [29] list 14 generations from Abraham to David (Inclusive of both Abraham and David), 14 generations from David to the exile (Inclusive of David and Josiah) and 14 from the exile to Jesus (inclusive of Jeconiah and Jesus) Thus, David’s generation is counted twice.

Michelangelo’s Josiah-Jechoniah-Sheatiel. Josiah is generally seen as the man on the right with Jechoniah being the child on his knee. The boy being held by the woman is intended as one of Jechoniah’s brothers.

The explanation supported by most scholars today is that Jeconiah has been confused with an individual of a similar name. Almost all other sources report that a king named Jehoiakim lay between Josiah and Jeconiah, and since the second theophory in the name Jeconiah (the ..iah) is transposed to the middle of his name in the Book of Kings, as Jehoiachin, it is plausible that the author of Matthew or a later scribe confused Jehoiakim for Jehoiachin. This would also explain why the text identifies Josiah as Jeconiah’s father rather than grandfather, and why Jeconiah, usually regarded as an only-child, is listed as having a number of brothers, a description elsewhere considered more appropriate for Jehoiakim.{

Curse on Jehoiakim[]

Jeremiah prophesied that King Jehoiakim would be killed by the enemy and no biological descendant of his would claim the throne. “Now this is what the LORD says about King Jehoiakim of Judah: He will have no heirs to sit on the throne of David. His dead body will be thrown out to lie unburied-exposed to the heat of the day and the frost of the night.” (Jeremiah 36:30.) Here is yet another problematic issue raised by the genealogies. However, the solution offered by many Christians[30] is this: Luke’s genealogy, as seen by what may be considered linguistic evidence, is in fact Mary’s, not Joseph’s, and the record in Matthew is his. If this is the case, the point is continued, then God’s curse is not undermined, as Jesus was not the biological son of Joseph.

Virgin birth[]

Annunciation by Fabrizio Boschi

The Gospels declare that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph, but by the power of the Holy Spirit while Mary was still a virgin, in fulfillment of prophecy. Thus, in mainstream Christianity and Islam, Jesus is regarded as being literally the “only begotten son”[31] of God, while Joseph is regarded as his foster father.

Matthew immediately follows the genealogy of Jesus with:

This is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about: His mother Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be with child through the Holy Spirit.[32]

Likewise, Luke tells of the Annunciation:

“How will this be,” Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?” The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. So the holy one to be born will be called the Son of God.”[33]

The question then arises, why do both Gospels seem to trace the genealogy of Jesus through Joseph, when they deny that he is his biological father? Augustine considers it a sufficient answer that Joseph was the father of Jesus by adoption, his legal father, through whom he could rightfully claim descent from David.[34]

Tertullian, on the other hand, argues that Jesus must have descended from David by blood through his mother Mary.[35] He sees Biblical support in Paul’s statement that Jesus was “born of a descendant of David according to the flesh”.[36] Affirmations of Mary’s Davidic ancestry are found early and often,[37] and some see a strong implication in these sources that at least one evangelist actually records Jesus’ maternal ancestry.

Extra-biblical accounts[]

Giotto di Bondone, The Meeting at the Golden Gate, 1305.

The Bible says nothing explicitly about the ancestry of Mary, nor does it address the apparent inconsistency between the genealogies in Matthew and Luke. There are, however, several early sources offering further details.

Patristic[]

The apocryphal Protevangelium of James (probably of the second century) tells of the miraculous birth of Mary to her parents, Joachim and Anne. It further relates that Joseph, before his marriage to Mary, was an elderly widower with children of his own. Joachim and Anne, who were eventually accepted into the canon of saints, are named in a number of other early sources[38] as Mary’s parents, but this apocryphal text, which was later condemned, was so widely influential that it is not clear whether the names rest on any other independent tradition.

Africanus, writing in the third century, is the first to reconcile the apparent contradiction between the two Gospel genealogies. Citing the records of the desposyni, he details a levirate marriage:

Matthan and Melchi, having taken the same woman to wife in succession, begat children who were uterine brothers, as the law did not prevent a widow, whether such by divorce or by the death of her husband, from marrying another. By Estha, then—for such is her name according to tradition—Matthan first, the descendant of Solomon, begets Jacob; and on Matthan’s death, Melchi, who traces his descent back to Nathan, being of the same tribe but of another family, having married her, as has been already said, had a son Eli. Thus, then, we shall find Jacob and Eli uterine brothers, though of different families. And of these, the one Jacob having taken the wife of his brother Eli, who died childless, begat by her the third, Joseph—his son by nature and by account. Whence also it is written, “And Jacob begat Joseph.” But according to law he was the son of Eli, for Jacob his brother raised up seed to him.[39]

A Jewish tradition relating Mary to Luke’s genealogy is recorded in the Doctrina Jacobi (written in 634), in which a Tiberian rabbi mocks the Christian veneration of Mary by recounting her genealogy according to the tradition of the Jews of Tiberias.[40] A century later, John of Damascus and others report the same information, only inserting an extra generation, Barpanther (Aramaic for son of Panther, thus indicating a misunderstood Aramaic source).[41] A certain prince Andronicus later found the same polemic in a book belonging to a rabbi named Elijah:[42]

Why do Christians extol Mary so highly, calling her nobler than the Cherubim, incomparably greater than the Seraphim, raised above the heavens, purer than the very rays of the sun? For she was a woman, of the race of David, born to Anne her mother and Joachim her father, who was son of Panther. Panther and Melchi were brothers, sons of Levi, of the stock of Nathan, whose father was David of the tribe of Judah.[43]

Each of these texts then goes on to describe, just as in Africanus (but omitting the name of Estha), how Melchi was related to Joseph through a levirate marriage.

Oddly, Melchi is thus always described as the father of Eli, while Luke reads “Eli, son of Matthat, son of Levi, son of Melchi.” Bede assumed that Africanus was mistaken and corrected Melchi to Matthat.[44] Since papponymics were common in this period,[45] however, it would not be surprising if Matthat were also named Melchi after his grandfather.

Controversy has surrounded the name Panther mentioned above, because of a charge by Celsus (writing about 178) that Jesus was actually an illegitimate son of a soldier named Panther.[46] Epiphanius, in refutation of Celsus, writes that Joseph and Cleopas were sons of “Jacob, surnamed Panther.”[47] A connection is often seen to the Ben Pandera mentioned in the Talmud.

Syriac texts of about the sixth century give a somewhat different version. The Cave of Treasures elaborates on Matthew’s genealogy, providing the mother of each post-exilic generation. It states that Joachim, there called Jonachir (Yōnākhīr), was a son of Matthan and twin brother of Jacob; his wife Anne, also called Dīnā, was daughter of Pākōdh.[48] The Muslim historian Al-Ṭabarī likewise reports that Mary’s father (whom he of course calls `Imrān) was a son of Māthān, and that Anne was daughter of Fāqūd son of Qabil.[49] The Syriac infancy gospel also identifies Mary’s parents as Yōnākhīr son of Matthan, and Dīnā, later renamed Anne; but it adds a somewhat different account of the levirate marriage, reversing the roles of Jacob and Eli and making Estā the mother of Joseph.[50]

Fascination with the life and family of Anne led to the spread of numerous medieval legends about her and inspired the artistic motif of the Holy Kinship. A number of medieval sources offer conflicting accounts of the parents of Anne:

- Byzantine sources record a tradition showing precisely how Mary was related to Elizabeth.[51] Andronicus refers to the above mentioned jewish book as a source for this tradition.[42] It can be summarized as follows:

There were three sisters of Bethlehem, daughters of Matthan the priest, and Mary his wife, under the reign of Cleopatra and Sosipatrus, before the reign of Herod, the son of Antipater: the eldest was Mary, the second was Sobe, the youngest’s name was Anne. The eldest being married in Bethlehem, had for daughter Salome the midwife; Sobe the second likewise married in Bethlehem, and was the mother of Elizabeth; last of all the third married in Galilee, and brought forth Mary the mother of Christ.[52]

- Syriac and Islamic texts, as noted above, name Pākōdh (Fāqūd) as Anne’s father.

- The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew names her father as Issachar of the tribe of Judah.[53] Later elaborations name her mother as Susanna.[54]

- By the fifteenth century, another account was current naming her parents as Stollanus and Emerentia.[55]

- Anne Catherine Emmerich, a nineteenth-century mystic, claimed to have visions revealing the ancestry of Mary in some detail—combining several medieval versions, she names Anne’s parents as Eliud and Ismeria.[56]

Islam[]

The Qur'an upholds the virgin birth of Jesus (`Īsā)[57] and thus considers his genealogy only through Mary (Maryam).

Mary is very highly regarded in the Qur’an, the nineteenth sura being named for her. She is called a daughter of `Imrān,[58] whose family is the subject of the third sura. The same Mary (Maryam) is also called a sister of Aaron (Hārūn) in one place,[59] and although this is often seen as an anachronistic conflation with the Old Testament Miriam (having the same name), who was sister to Aaron (Hārūn) and daughter to Amram (`Imrān), the phrase is probably not to be understood literally.[60]

Explanations for divergence[]

The two Biblical genealogies seem to disagree not only on on the name of Joseph’s father, but on the entire lineage back to David.

This apparent contradiction has been a source of great difficulty. Augustine, for example, took great care on several occasions to refute every purported inconsistency in the Gospel genealogies, not only because the Manichaeans in his day were using these inconsistencies as fodder for attacking Christianity,[61] but also because he himself had seen them in his youth as cause for doubting the veracity of the Gospels.[62]

Several theories have been advanced to explain the divergence of the two Gospel genealogies:

- That Joseph had two fathers—one natural and one legal—as a result of a Levirate marriage involving uterine brothers.

- That one of the genealogies is actually through Mary rather than Joseph.

- That one or both of the genealogies are incorrect.

Levirate marriage[]

The earliest tradition that explains this divergence records a complex scenario involving the Jewish law of levirate marriage, whereby, upon the death of a childless man, his brother would marry the widow in order to produce a son for the deceased man. Such a son would then have two fathers, one natural and one legal.

Africanus, in his third-century Epistle to Aristides,[39] reports a tradition of the desposyni that Joseph was born from just such a levirate marriage involving uterine brothers (see above).

According to Africanus, Joseph’s natural father was Jacob son of Matthan, as given in Matthew, while his legal father was Heli son of Melchi (sic), as given in Luke. Joseph’s grandmother Estha first married Matthan and bore Jacob, then married Melchi and bore Heli. When Heli died without issue, his half-brother Jacob married the widow and begot Joseph.

To many, the whole scenario seems rather contrived, as the only explanation for how, under Jewish law, a man could have two completely different ancestries. It has been questioned, for example, whether a levirate marriages actually occurred among uterine brothers[63]—they are expressly excluded in the Mishnah.[64]

Nevertheless, the patristic tradition eagerly embraced this explanation, and it remained widely accepted until the Reformation.

Augustine, while mentioning this possibility, proposes a simpler alternative as well, that Joseph became a son of Heli by ordinary adoption (Matthew is assumed to give the natural lineage, since he explicitly says “begot”).[65]

Maternal ancestry[]

A more straightforward explanation is that Luke’s genealogy is of Mary, with Heli being her father, while Matthew’s describes the genealogy of Joseph.[1]

Luke’s text says that Jesus was “a son, as was supposed, of Joseph, of Heli” (in the Greek: υιος ως ενομιζετο ιωσηφ του ηλι).[66] The qualification has traditionally been understood as acknowledgment of the virgin birth, but some instead see a parenthetical expression: “a son (as was supposed of Joseph) of Heli.”[67] In this interpretation, Jesus is called a son of Heli because Heli was his maternal grandfather, his nearest male ancestor.[1] A variation on this idea is to explain “Joseph son of Heli” as meaning a son-in-law,[68] perhaps even an adoptive heir to Heli through his only daughter Mary.[3] An example of the Old Testament use of such an expression is Jair, who is called “Jair son of Manasseh”[69] but was actually son of Manasseh’s granddaughter.[70] In any case, the argument goes, it is natural for the evangelist, acknowledging the unique case of the virgin birth, to give the maternal genealogy of Jesus, while expressing it a bit awkwardly in the traditional patrilinear style.

Lightfoot[68] sees confirmation in an obscure passage of the Talmud,[71] which, as he reads it, refers to “Mary daughter of Eli”; however, both the identity of this Mary and the reading are doubtful.[72] Patristic tradition, on the contrary, consistently identifies Mary’s father as Joachim. It has been suggested that Eli is short for Eliakim,[1] which in the Old Testament is an alternate name of King Jehoiakim,[73] for whom Joachim is named.

The theory neatly accounts for the genealogical divergence while accepting the text of the Gospel. It is consistent with the early tradition ascribing a Davidic ancestry to Mary. It is also consistent with Luke’s intimate acquaintance with Mary, in contrast to Matthew’s focus on Joseph’s perspective. On the other hand, there is no explicit indication whatsoever, either in the Gospel or in any early tradition, that the genealogy is Mary’s.

The claim that Luke gives Mary’s genealogy was first put forth by Annius of Viterbo in 1498[74] and quickly grew in popularity. It has gained acceptance by countless scholars (though by no means all), and remains the most frequently cited harmonization of the Gospel genealogies.

A minority view holds that while Luke gives the genealogy of Joseph, Matthew gives the genealogy of Mary. Though a few ancient authorities seem to offer this interpretation,[75][76] the Greek text as it stands is plainly against it. However, an emendation has been proposed saying “Jacob begot Joseph, the father of Mary.”[77] Some argue that here the Aramaic original of Matthew used the word gowra (which could mean father), which, in the absence of vowel markings, was read by the Greek translator as gura (husband).[78] Such an error, whatever its origin, would certainly be understandable if Mary had a father and a husband of the same name. Futhermore, the theory has the advantage of completing Matthew’s final tesseradecad.

Fabrication or error[]

A common explanation for the inconsistency of the two genealogies is that at least one of them, and possibly both, are simply fabricated.[79]

Clarke believes that the two accounts cannot be harmonized and are “theological” constructs. He has suggested that Matthew wants to underscore birth of a messianic child of royal lineage (mentioning Solomon) whereas Luke’s genealogy is priestly (mentioning Levi).[80][81]

Zadok is generally placed as having lived some 150 years after the start of Zerubbabel’s period. This is a long period of time for just Zerubbabel, Abihud, Eliakim, and Azor to cover, and so many scholars feel an accurate list would be longer than Matthew’s, more like Luke’s genealogy, which has far more names for the period. That this part of the genealogy in Matthew lacks papponymics has led Albright and Mann to speculate that the original names covering this period became telescoped together, owing to repetitive re-occurrences of names; whereas Luke’s genealogy contains several repeated groups of closely similar names, suggesting that Luke inadvertently, or deliberately, duplicated them.[22]

The names between Zerubbabel and Zadok - Abihud, Eliakim, and Azor - are not known in any records dating from before the Gospel of Matthew, immediately leading many scholars, including Gundry, to believe that the author of Matthew simply made them up.[21] In the eyes of such scholars, once the list moves away from the accepted genealogy of Jewish leaders it is fabricated until it reaches the known territory of Joseph’s grandfather. The names listed are names that were frequent in the period of history, and so Gundry sees the author as having drawn the names from random parts of 1 Chronicles, disguising them to not make the copying obvious: According to Gundry

- The author of Matthew liked the meaning “son of Judah” that lies behind the name Abihu, a priest, and modified it to become Abiud.

- The author then changed the name of Abihu’s successor, Eliezer, into Eliakim to link him with the Eliakim of Isaiah 22 and also to link him with Jehoiakim (an identical name when theophory is taken into account)

- The third name comes from another significant priest - Azariah - which the author shortened to Azor.

- Achim is an abbreviation by the author of the name of Zadok’s son, Achimaas

- Eliezer, another figure from 1 Chronicles, is turned into Eliud.

According to Barbara Thiering in her book Jesus the man, Jacob and Heli are one and the same. Heli took the name “Jacob” for his title as patriarch. The true genealogy is that in Luke’s Gospel, and in Matthew’s Gospel Heli’s line is grafted in to the royal line running down through Solomon. (It should be noted that Thiering’s theories have found little acceptance with either secular or religious academia).

Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel[]

The genealogies in Luke and Matthew appear to briefly converge at Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, though they differ both above Shealtiel and below Zerubbabel. This is also the point where Matthew departs from the Old Testament record.

Zerubbabel displays a plan of Jerusalem to Cyrus the Great

In the Old Testament, Zerubbabel was a hero who led the Jews back from Babylon about 520 BCE, governed Judah, and rebuilt the temple. Several times he is called a son of Shealtiel.[82] He appears once in the genealogies in the Book of Chronicles,[83], where his descendants are traced for several generations, but the passage has a number of difficulties.[84] While the Septuagint text here gives his father as Shealtiel, the Masoretic text instead substitutes Shealtiel’s brother Pedaiah—both sons of King Jeconiah, according to the passage. Some, accepting the Masoretic reading, suppose that Pedaiah begot a son for Shealtiel through a levirate marriage, or that two Zerubbabels were cousins, but most scholars now accept the Septuagint reading as original, in agreement with Matthew and all other accounts.[85]

The appearance of Zerubbabel and Shealtiel in Luke may be no more than a coincidence of names. Shealtiel is given a completely different ancestry, and Zerubbabel a different son. Furthermore, interpolation between known dates would put the birth of Luke’s Shealtiel at the very time when the celebrated Zerubbabel led the Jews back from Babylon. Thus, it is likely that Luke’s Shealtiel and Zerubbabel were distinct from, and even named after, Matthew’s.[1]

If they are the same, as many insist, then the question arises of how Shealtiel, like Joseph, could have two fathers. Yet another complex levirate marriage has often been invoked.[1] Bauckham, however, argues for the authenticity of Luke alone. In this view, the genealogy in Chronicles is a late addition grafting Zerubbabel onto the lineage of his predecessors, and Matthew has simply followed the royal succession. In fact, Bauckham says, Zerubbabel’s legitimacy hinged on descending from David through Nathan rather than through the prophetically cursed ruling line.[10]

The name Rhesa, given in Luke as the son of Zerubbabel, is usually seen as the Aramaic word rēʾšāʾ, meaning head or prince. It might well befit a son of Zerubbabel, but some see the name as a misplaced title of Zerubbabel himself.[10] If so, the next generation in Luke, Joanan, might be Hananiah in Chronicles. Subsequent names in Luke, as well as Matthew’s next name Abihud, cannot be identified in Chronicles on more than a speculative basis.

Fulfillment of prophecy[]

By the time of Jesus, it was already commonly understood that several prophecies in the Old Testament promised a Messiah descended from King David.[5][86] Thus, in tracing the Davidic ancestry of Jesus, the Gospels aim to show that these messianic prophecies are fulfilled in him.

The prophecy of Nathan[87]—understood as foretelling a son of God who would inherit the throne of his ancestor David and reign forever—is quoted in Hebrews[88] and strongly alluded to in Luke’s account of the Annunciation.[89] Likewise, the Psalms[90] record God’s promise to establish the seed of David on his throne forever, while Isaiah[91] and Jeremiah[92] speak of the coming reign of a righteous king of the house of David.

David’s ancestors are also understood as progenitors of the Messiah in several prophecies.[5] Isaiah’s description of the branch or root of Jesse[93] is cited twice by Paul as a promise of the Christ.[94] Even Genesis is seen as promising the Messiah’s descent from Judah[95] and from Abraham[96]. In the earliest messianic prophecy of all, immediately after the sin of Adam and Eve, God promises that the serpent’s head will be crushed by “the seed of the woman”[97]—in the simplest sense, this refers to Eve, the first woman, but Christian exegesis sees a reference to Mary.

Matthew also presents the virgin birth of Jesus as fulfillment of Isaiah 7:14, which he quotes.[98]

Desposyni[]

The Desposyni (from Greek δεσπόσυνος (desposunos) “of or belonging to the master or lord”) was a sacred name reserved only for Jesus’ blood relatives. The closely related word δεσπότης (despotes), literally meaning despot, but more generally meaning a lord, master, or ship owner, is commonly used of God, human slave-masters, and of Jesus in the reading Luke 13:25 found in Papyrus 75, in Jude 1:4, and possibly in 2nd Peter 2:1. In Ebionite belief, the desposyni included his mother Mary, his father Joseph, his un-named sisters, and his brothers James the Just, Joses, Simon and Jude; in modern mainstream Christian belief, Mary is counted as a blood relative, Joseph as a foster father or step father and the rest as half-siblings (Protestant belief) or step-siblings or cousins (Catholic and Orthodox).

See also[]

Notes[]

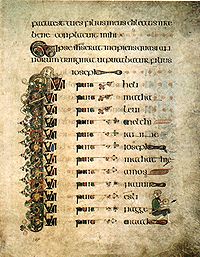

Luke’s genealogy of Jesus, from the Book of Kells, transcribed by Celtic monks circa 800

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5

Anthony Maas (1913), "Genealogy of Christ", Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company. Cite error: Invalid

Anthony Maas (1913), "Genealogy of Christ", Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company. Cite error: Invalid <ref>tag; name "cathen" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "cathen" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "cathen" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ A famous example is the Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate, Against the Galileans.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 John Nolland (2005), The Gospel of Matthew: a commentary on the Greek text, Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, p. 70, ISBN 9780802823892, considers this harmonization “the most attractive.”

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:5; but also see Zechariah 12:12.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Donald Juel (1992), Messianic Exegesis: Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, pp. 59–88, ISBN 9780800627072.

- ↑ Luke 3:22

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, De consensu evangelistarum (On the Harmony of the Gospels), 2.4.12–13 (text).

- ↑ Matthew 18:21–22; cf. Genesis 4:24

- ↑ 1 Enoch 10:11–12

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Richard Bauckham (2004), Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church, London: T & T Clark International, pp. 315–373, ISBN 9780567082978.

- ↑ Irenaeus, Adversus haereses (Against Heresies), 3.22.3 (text).

- ↑ Wieland Willker (2009), A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels, vol. 3: Luke (6th ed.), TVU 39, http://www-user.uni-bremen.de/~wie/TCG/TC-Luke.pdf, retrieved 2009-03-25. Willker details the textual evidence underlying the NA27 reading.

- ↑ For example, Martin A. Shue, "Can you repeat those names?", What’s in a Name?, http://www.geocities.com/avdefense1611/repeatnames.html, retrieved 2009-03-25

- ↑ Philip Schaff (1882), The Gospel According to Matthew, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Luke 1:5,36

- ↑ For example, Gregory Nazianzen, Carmen 18

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIIa, q.31, a.2 (text)

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:11–12, Matthew 1:9

- ↑ See and compare Ezra 7:3 with 1st Chronicles 6:7–10 thus giving precedence to Matthew’s stylistic choices.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Raymond E. Brown (1977), The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke, London: G. Chapman, ISBN 9780225662061.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Robert H. Gundry (1982), Matthew: A Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 9780802835499. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "gundry" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "gundry" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "gundry" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "gundry" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 William F. Albright & C. S. Mann (1971), Matthew: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible, 26, New York: Doubleday & Company, ISBN 9780385086585.

- ↑ Amy-Jill Levine (1998), "Matthew", in Carol A. Newsom & Sharon H. Ringe, Women’s Bible Commentary, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 9780664257811.

- ↑ payment was a goat held in arrears but secured with Judah’s staff and seal

- ↑ Millar Burrows (1940), "Levirate Marriage in Israel", Journal of Biblical Literature 59 (1), http://www.jstor.org/pss/3262301.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Graham N. Stanton (1989), The Gospels and Jesus, Oxford University Press, p. 67, ISBN 9780192132413. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "stanton" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Markus Bockmuehl & Donald A. Hagner (2005), The Written Gospel, Cambridge University Press, p. 191, ISBN 0521832853.

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:4–19 (LXX)

- ↑ Matthew 1:17

- ↑ John Gill’s comments on Heli being Mary’s father

- ↑ John 3:16

- ↑ Matthew 1:18

- ↑ Luke 1:34–35

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, De consensu evangelistarum (On the Harmony of the Gospels), 2.1.2–4 (text); Sermon 1, 16–21 (text).

- ↑ Tertullian, |De carne Christi (On the Flesh of Christ), 20-22 (text).

- ↑ Romans 1:3

- ↑ Justin Martyr, Dialogus cum Tryphone Judaeo (Dialogue with Trypho), 100 (text). Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians, 18 (text).

- ↑ Besides the apocryphal nativity narratives, the earliest seems to be Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion (Against Heresies), 79.5.5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Sextus Julius Africanus, Epistula ad Aristidem (Epistle to Aristides) (text).

- ↑ Doctrina Jacobi, 1.42 (Patrologia Orientalis 40.67–68). Translated in part by A. Lukyn Williams (1935), Adversus Judaeos: a bird's-eye view of Christian apologiae until the Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, pp. 155–156, http://books.google.com/books?id=6m43AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA155.

- ↑ John of Damascus, De fide orthodoxa (An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith), 4.14. Andrew of Crete, Oration 6 (On the Circumcision of Our Lord) (Patrologia Graeca 97.916). Epiphanius the Monk, Sermo de vita sanctissimae deiparae (Life of Mary) (Patrologia Graeca 120.189). The last apparently draws from a lost work of Cyril of Alexandria, perhaps via Hippolytus of Thebes.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Andronicus, Dialogus contra Iudaeos, 38 (Patrologia Graeca 133.859–860). The author of this dialogue is now believed to be a nephew of Michael VIII living about 1310.

- ↑ Translation from A. Lukyn Williams (1935), Adversus Judaeos: a bird's-eye view of Christian apologiae until the Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, pp. 184–185, http://books.google.com/books?id=6m43AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA185.

- ↑ Bede, In Lucae evangelium expositio (On the Gospel of Luke), 1,3 (PL 92.361-362).

- ↑ Barbara Sivertsen (2005), "New testament genealogies and the families of Mary and Joseph", Biblical Theology Bulletin 35 (2): 43–50, http://www.thefreelibrary.com/New+testament+genealogies+and+the+families+of+Mary+and+Joseph-a0133946349

- ↑ Origen, Contra Celsum (Reply to Celsus), 1.32 (text).

- ↑ Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion (Against Heresies), 78.7.5.

- ↑ E. A. Wallis Budge, ed. (1927), The Book of the Cave of Treasures, p. 194.

- ↑ Moshe Perlmann, ed. (1987), "The Ancient Kingdoms", The History of al-Tabari, 4, Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, pp. 102–103, ISBN 9780887061813. Another version from Ibn Isḥāq is also quoted, making `Imrān a son of King Josiah, evidently by conflation of `Imrān with King Jehoiakim through his namesake Joachim.

- ↑ E. A. Wallis Budge, ed. (1899), The History of the Blessed Virgin Mary and The History of the Likeness of Christ which the Jews of Tiberias Made to Mock at, 2, pp. 3–4, http://books.google.com/books?id=rN5JAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA3.

- ↑ The earliest are of the eighth century: Andrew of Crete, Canon in B. Mariae Natalem, ode 6 (Patrologia Graeca 97.1325); and Epiphanius the Monk, Sermo de vita sanctissimae deiparae (Life of Mary) (Patrologia Graeca 120.189).

- ↑ Translation from Charles Wheatly (1794), A Rational Illustration of the Book of Common Prayer, p. 63, http://books.google.com/books?id=ZYENAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PA63. Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos, Historia ecclesiastica, 2.3 (Patrologia Graeca 145.760), also records this passage, citing Hippolytus of Portus—actually Hippolytus of Thebes, according to J. A. Cerrato (2002), Hippolytus Between East and West, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, p. 113, ISBN 9780199246960.

- ↑ Pseudo-Matthew 1:2 (text)

- ↑ Analecta Bollandiana, 52, 1934, pp. 357–361.

- ↑ Angelika Dörfler-Dierken (1992), Die Verehrung der heiligen Anna in Spätmittelalter und früher Neuzeit, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 146–153, ISBN 9783525551585.

- ↑ Anne Catherine Emmerich, The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, ch. 1 (text)

- ↑ Qur'an 19:20–22

- ↑ Qur'an 66:12;Qur'an 3:35–36

- ↑ Qur'an 19:28

- ↑ Thomas Patrick Hughes, ed. (1995), "`Imrān", A Dictionary of Islam, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 9788120606722.

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, Contra Faustum (Reply to Faustus) (text).

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 1, 6 (text).

- ↑ Gerard Mussies (1986), "Parallels to Matthew's Version of the Pedigree of Jesus", Novum Testamentum 28 (1): 41, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1560666.

- ↑ Yebamoth 1.1

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 1, 27–29 (text).

- ↑ Luke 3:23

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIIa, q.31, a.3, Reply to Objection 2 (text), offers this interpretation, that Luke calls Jesus a son of Heli, without making the leap to explain why.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 John Lightfoot (1859) [1663], Horæ Hebraicæ et Talmudicæ, 3, p. 55, http://philologos.org/__eb-jl/luke03.htm. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "lightfoot" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Numbers 32:41; Deuteronomy 3:14; 1 Kings 4:13

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 2:21–23;1 Chronicles 7:14

- ↑ j. Hagigah 77d.

- ↑ Mary’s Genealogy & the Talmud, http://www.frontline-apologetics.com/mary_genealogy_talmud.html, retrieved 2009-03-25

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 36:4

- ↑ Annius of Viterbo, Antiquitatum Variarum, 1498. In this notorious forgery, Joachim is identified as Heli in a passage ascribed to Philo.

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, 21. (text) “And in the Gospel according to Matthew, the genealogy which begins with Abraham is continued down to Mary the mother of the Lord.”

- ↑ Victorinus of Pettau, In Apocalypsin (Commentary on the Apocalypse), 4.7–10 (text). “Matthew strives to declare to us the genealogy of Mary, from whom Christ took flesh.”

- ↑ Harold A. Blair (1964), "Matthew 1,16 and the Matthaean Genealogy", Studia Evangelica 2: 149–154, apud Joel B. Green, ed. (1992), Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, p. 258.

- ↑ Andrew Gabriel Roth (2003), Proofs of Peshitta Originality in the Gospel According to Matthew & the Gowra Scenario: Exploding the Myth of a Flawed Genealogy, http://aramaicnttruth.org/downloads/Peshitta%20Matthew%20and%20the%20Gowra%20Scenario.pdf, retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Geza Vermes (2006), The Nativity: History and Legend, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0141024461.

- ↑ Howard W. Clarke (2003), The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers, Indiana University Press, p. 1, ISBN 9780253216007.

- ↑ David D. Kupp (1996), Matthew’s Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God’s People in the First, Cambridge University Press, p. 170, ISBN 0521570077.

- ↑ Ezra 3:2,8; 5:2; Nehemiah 12:1; Haggai 1:1,12,14

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:17–24

- ↑ James C. VanderKam (2004), From Joshua to Caiaphas: High Priests after the Exile, Minneapolis, Minn.: Fortress Press, pp. 104–106, ISBN 9780800626174.

- ↑ Sara Japhet (1993), I & II Chronicles: A Commentary, Louisville, Ky.: Westminster/John Knox Press, p. 100, ISBN 9780664226411.

- ↑ cf. John 7:42; Matthew 22:41–42

- ↑ 2 Samuel 7:12–16

- ↑ Hebrews 1:5

- ↑ Luke 1:32–35

- ↑ Psalms 89:3-4; Psalms 132:11

- ↑ Isaiah 16:5

- ↑ Jeremiah 23:5-6

- ↑ Isaiah 11:1–10

- ↑ Acts 13:23; Romans 15:12

- ↑ Genesis 49:10, alluded to in Galatians 3:19

- ↑ Genesis 22:18, cited in Galatians 3:16

- ↑ Genesis 3:15

- ↑ Matthew 1:22–23, citing Isaiah 7:14

External links[]

Media related to Genealogy of Jesus Christ on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Genealogy of Jesus Christ on Wikimedia Commons- Information on the Michaelangelo frescoes

- Multiple translations

- Anne Catherine Emmerich, Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Bible Study Manual on Genealogy of Jesus

- Genealogy of Jesus at Complete-Bible-Genealogy.com

- The Baptism and the Genealogy of Jesus

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original article was at Genealogy of Jesus. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |