- This article is about the Torah portion "Noach." For the Biblical figure, see Noah.

Noach or Noah (נח — Hebrew for the name “Noah,” the third word, and first distinctive word, of the parshah) is the second weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It constitutes Genesis 6:9–11:32. Jews read it on the second Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in October or November.

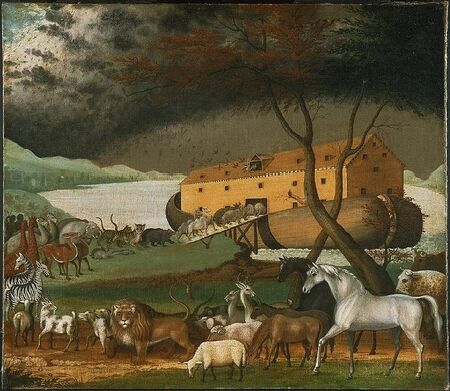

Noah's Ark (painting by Edward Hicks)

Summary[]

The Building of Noah's Ark (painting by a French master of 1675)

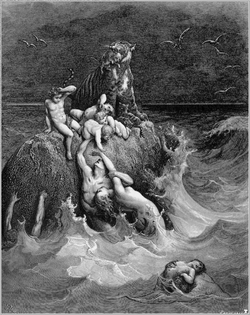

The Deluge (illustration by Gustave Doré from the 1865 La Sainte Bible)

The flood[]

Noah was a righteous man, blameless in his age, who walked with God. (Genesis 6:9) Noah had three sons: Shem, Ham, and Japheth. (Genesis 6:10) God saw that all flesh on earth had become corrupt and lawless, and God told Noah that God had decided to bring a flood to destroy all flesh. (Genesis 6:11–17) God directed Noah to make an ark of gopher wood and cover it with pitch. (Genesis 6:14) The ark was to be 300 cubits long, 50 cubits wide, and 30 cubits high, and have an opening for daylight near the top, an entrance on its side, and three decks. (Genesis 6:15–16) God told Noah that God would establish a covenant with Noah, and that he, his sons, his wife, his sons’ wives, and two of each kind of beast — male and female — would survive in the ark. (Genesis 6:18–20)

Seven days before the flood, God told Noah to go into the ark with his household, and to take seven pairs of every clean animal and every bird, and one pair of every other animal, to keep their species alive. (Genesis 7:1–4) When Noah was 600 years old, the flood came, and that same day, Noah, his family and the beasts went into the ark, and God shut him in. (Genesis 7:6–16) The rains fell 40 days and 40 nights, the waters swelled 15 cubits above the highest mountains, and all flesh with the merest breath of life died, except for Noah and those with him on the ark. (Genesis 7:12–23)

When the waters had swelled 150 days, God remembered Noah and the beasts, and God caused a wind to blow and the waters to recede steadily from the earth, and the ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat. (Genesis 7:24–8:4) At the end of 40 days, Noah opened the window and sent out a raven, and it went to and fro. (Genesis 8:6–7) Then he sent out a dove to see if the waters had decreased from the ground, but the dove could not find a resting place, and returned to the ark. (Genesis 8:8–9)

The Return of the Dove (painting by John Everett Millais)

He waited another seven days, and again sent out the dove, and the dove came back toward evening with an olive leaf. (Genesis 8:10–11) He waited another seven days and sent out the dove, and it did not return. (Genesis 8:12) When Noah removed the covering of the ark, he saw that the ground was drying. (Genesis 8:13) God told Noah to come out of the ark with his family and to free the animals. (Genesis 8:16)

Landscape with Noah's Thank Offering (painting by Joseph Anton Koch)

Then Noah built an altar to God and offered burnt offerings of every clean animal and of every clean bird. (Genesis 8:20) God smelled the pleasing odor and vowed never again to doom the earth because of man, as man's imaginings are evil from his youth, but God would preserve the seasons so long as the earth endured. (Genesis 8:21–22)

God blessed Noah and his sons to be fertile and increase, and put the fear of them into all the beasts, which God gave into their hands to eat. (Genesis 9:1–3) God prohibited eating flesh with its life-blood in it. (Genesis 9:4) God would require a reckoning of every man's and beast's life-blood, and whoever shed the blood of man would have his blood shed by man, for in God's image did God make man. (Genesis 9:5–6) God told them to be fertile and increase. (Genesis 9:7) And God made a covenant with Noah, his sons, and every living thing that never again would a flood destroy the earth. (Genesis 9:8–11) God set the rainbow in the clouds as the sign of God's covenant with earth, so that when the bow appeared in the clouds, God would remember God's covenant and the waters would never again flood to destroy all flesh. (Genesis 9:12–17)

Noah cursing Canaan (illustration by Gustave Doré from the 1865 La Sainte Bible)

The curse on Canaan[]

Noah was the first to plant a vineyard, and he drank himself drunk, and uncovered himself within his tent. (Genesis 9:20–21) Ham, the father of Canaan, saw his father's nakedness and told his two brothers. (Genesis 9:22) Shem and Japheth placed a cloth against both their backs and, walking backward, covered their father, without seeing their father's nakedness. (Genesis 9:23) When Noah woke up and learned what Ham had done to him, he cursed Ham's son Canaan to become the lowest of slaves to Japheth and Shem, prayed that God enlarge Japheth, and blessed the God of Shem. (Genesis 9:24–27)

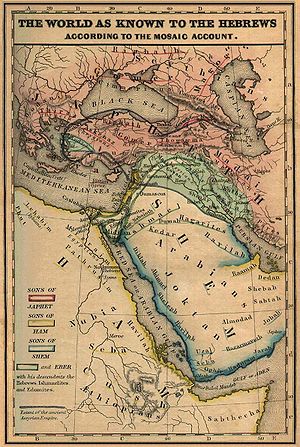

The dispersion of the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth (map from the 1854 Historical Textbook and Atlas of Biblical Geography)

Noah lived to the age of 950 and then died. (Genesis 9:28–29)

Noah’s descendants[]

Genesis 10 sets forth the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, from whom the nations branched out over the earth after the flood. Among Japheth's descendants were the maritime nations. (Genesis 10:2–5) Ham's son Cush had a son named Nimrod, who became the first man of might on earth, a mighty hunter, king in Babylon and the land of Shinar. (Genesis 10:6–10) From there Asshur went and built Nineveh. (Genesis 10:11–12) Canaan's descendants — Sidon, Heth, the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites — spread out from Sidon as far as Gerar, near Gaza, and as far as Sodom and Gomorrah. (Genesis 10:15–19) Among Shem's descendants was Eber. (Genesis 10:21)

The Tower of Babel (painting by Pieter Bruegel)

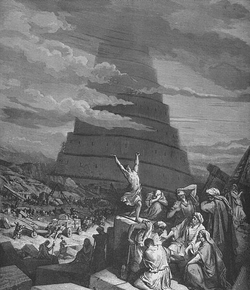

The Tower of Babel[]

Everyone on earth spoke the same language. (Genesis 11:1) As people migrated from the east, they settled in the land of Shinar. (Genesis 11:2) People there sought to make bricks and build a city and a tower with its top in the sky, to make a name for themselves, so that they not be scattered over the world. (Genesis 11:3–4) God came down to look at the city and tower, and remarked that as one people with one language, nothing that they sought would be out of their reach. (Genesis 11:5–6) God went down and confounded their speech, so that they could not understand each another, and scattered them over the face of the earth, and they stopped building the city. (Genesis 11:7–8) Thus the city was called Babel. (Genesis 11:9)

The line of Terah[]

Genesis 11 sets forth the descendants of Shem. Eight generations after Shem came Terah, who had three sons: Abram (who would become Abraham), Nahor, and Haran. (Genesis 11:10–26) Haran had a son Lot and two daughters Milcah and Iscah, and then died in Ur during the lifetime of his father Terah. (Genesis 11:27–28) Abram married Sarai, and Nahor married Haran's daughter Milcah. (Genesis 11:29) Sarai was barren. (Genesis 11:30) Terah took Abram, Sarai, and Lot and set out together from Ur for the land of Canaan, but when they had come as far as Haran, they settled there, and there Terah died. (Genesis 11:31–32)

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Noah building the Ark (engraving by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Bible in Pictures)

Genesis chapter 6[]

The Mishnah concluded that the generation of the flood and the generation of the dispersion after the Tower of Babel were both so evil as to have no share in the world to come. (Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:3; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 107b–08a.) Rabbi Akiba deduced from the words of Genesis 7:23 that the generation of the flood will have no portion in the world to come; he read the words “and every living substance was destroyed” to refer to this world and the words “that was on the face of the ground” to refer to the next world. Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra deduced from the words “My spirit will not always enter into judgment with man” of Genesis 6:3 that God will neither revive nor judge the generation of the flood on Judgment Day. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 108a.)

Noah's Ark floats in the background while people struggle to escape the rising water of the Flood (fresco by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel)

The Tosefta taught that the generation of the flood acted arrogantly before God, thinking that because they had great rivers, they did not need God's rain, so God punished them using those same waters. (Tosefta Sotah 3:7–8.) The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the good that God lavished upon the generation of the flood led them to become arrogant. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 108a.)

The Tosefta taught that the flood killed people before animals (as seen in the order of Genesis 7:23), because man sinned first (as shown in Genesis 6:5). (Tosefta Sotah 4:11.)

Noah's Flood (image by Uriel Vidal)

Rabbi Hanan said in the name of Rabbi Samuel ben Isaac that as soon as Noah entered the ark, God prohibited his family from cohabitation, saying in Genesis 6:18: “you shall come into the ark, you, and your sons,” speaking of them apart, and, “your wife, and your sons’ wives,” speaking of them apart. When Noah left the ark, God permitted cohabitation to him again, saying in Genesis 8:16: “Go forth from the ark, you and your wife,” speaking of them together. (Genesis Rabbah 31:12.)

The deluge (painting by Wassilij Petrovich Wereschtschagin)

Genesis chapter 7[]

The Gemara read Genesis 7:8 to employ the euphemistic expression “not clean,” instead of the brief, but disparaging expression “unclean,” so as not to speak disparagingly of unclean animals. The Gemara reasoned that it was thus likely that Scripture would use euphemisms when speaking of the faults of righteous people, as with the words, “And the eyes of Leah were weak,” in Genesis 29:17. (Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 123a.)

Rabbi taught that, in conferring honor, the Bible commences with the greatest, in cursing with the least important. With regard to cursing, the Gemara reasoned that Rabbi must have meant the punishment of the Flood, as Genesis 7:23 says, “And He blotted out every living substance which was upon the face of the ground, both man and cattle,” starting with the people before the cattle. (Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 61a.)

Genesis chapter 8[]

A midrash taught that when Psalm 142:8 says, “Bring my soul out of prison,” it refers to Noah's imprisonment 12 months in the ark, and when Psalm 142:8 says, “for You will deal bountifully with me,” it refers to God's bounty to Noah when God told Noah in Genesis 8:16, “Go forth from the ark.” (Genesis Rabbah 34:1.)

Noah Descending from Ararat (painting by H. Ayvazovsky)

Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words, “After their kinds they went forth from the ark,” in Genesis 8:19 to teach that the animals went out by their families, not alone. Rabbi Hana bar Bizna taught that Abraham's servant Eliezer once inquired of Noah's son Shem about these words in Genesis 8:19, asking Shem how his family managed. Shem replied that they had a difficult time in the ark. During the day they fed the animals that usually fed by day, and during the night they fed those that normally fed by night. But Noah did not know what the chameleon ate. One day Noah was cutting a pomegranate, when a worm dropped out of it, and the chameleon ate it. From then on, Noah mashed up bran for the chameleon, and when the bran became wormy, the chameleon would eat. A fever struck the lion, so it lived off of its reserves rather than eating other animals. Noah discovered the avarshinah bird (some say the phoenix bird) lying in the hold of the ark and asked it if it needed food. The bird told Noah that it saw that Noah was busy and decided not to give him any more trouble. Noah replied by asking that it be God's will that the bird not perish, as Job 19:18 says, “Then I said: ‘I shall die with my nest, and I shall multiply my days as the phoenix.’” (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 108b.)

Rav Huna cited the report in Genesis 8:20 that Noah offered burnt offerings from every clean animal and bird to support the proposition in a Baraita that all animals were eligible to be offered, as the words “animal” (behemah) and bird (bear) refer to any animal or bird, and the term “animal” (behemah) includes wild beasts (hayyah). (Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 115b.)

Rabbi Haninah cited the report of Genesis 8:21 that “the Lord smelled the sweet savor; and . . . said . . . ‘I will not again curse the ground any more for man's sake,’” for the proposition that those who allow themselves to be pacified when drinking wine possesses some of the characteristics of the Creator. (Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 65a.)

Parshah Noach in the Torah scroll

Rav Awira (or some say Rabbi Joshua ben Levi) taught that the Evil Inclination has seven names. God called it “Evil” in Genesis 8:21, saying, “the imagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” Moses called it “the Uncircumcised” in Deuteronomy 10:16, saying, “Circumcise therefore the foreskin of your heart.” David called it “Unclean” in Psalm 51:12; Solomon called it “the Enemy” in Proverbs 25:21–22; Isaiah called it “the Stumbling-Block” in Isaiah 57:14; Ezekiel called it “Stone” in Ezekiel 36:26; and Joel called it “the Hidden One” in Joel 2:20. (Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 52a.)

Genesis chapter 9[]

The Rabbis interpreted Genesis 9 to set forth seven Noahide laws binding on all people: (1) to set up courts of justice, (2) not to commit idolatry, (3) not to commit blasphemy, (4) not to commit sexual immorality, (5) not to commit bloodshed (Genesis 9:6), (6) not to commit robbery, and (7) not to eat flesh cut from a living animal (Genesis 9:4). (Tosefta Avodah Zarah 8:4–6; see also Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 56a; Genesis Rabbah 34:8.) Rabbi Hanina taught that they were also commanded not to consume blood from a living animal. Rabbi Leazar taught that they were also commanded not to cross-breed animals. Rabbi Simeon taught that they were also commanded not to commit witchcraft. Rabbi Johanan taught that they were also commanded not to emasculate animals. And Rabbi Assi taught that the children of Noah were also prohibited to do anything stated in Deuteronomy 18:10–11: “There shall not be found among you any one that makes his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, one that uses divination, a soothsayer, or an enchanter, or a sorcerer, or a charmer, or one that consults a ghost or a familiar spirit, or a necromancer.” (Genesis Rabbah 34:8.) The Tosefta instructed that Israelites should not tempt anyone to violate a Noahide law. (Tosefta Demai 2:24.)

Rabbi Shimon ben Eleazar deduced from Genesis 9:2 that even a one-day-old child scares small animals, but said that the corpse of even the giant Og of Bashan would need to be guarded from weasels and rats. (Tosefta Shabbat 17:19.)

Rabbi Akiva said that it demonstrated the value of human beings that God created us in God's image, and that it was an act of still greater love that God let us know (in Genesis 9:6) that God had created us in God's image. (Mishnah Avot 3:14.) And Rabbi Akiva also said that whoever spills blood diminishes the Divine image. (Tosefta Yevamot 8:7.) Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah and Ben Azzai both said that whoever does not have children diminishes the Divine image (as demonstrated by proximity of the notice that God created us in God's image (Genesis 9:6) and the command to be fruitful and multiply (Genesis 9:7). (Tosefta Yevamot 8:7.)

Rabbi Meir taught that while it was certain that God would never again flood the world with water (Genesis 9:11), God might bring a flood of fire and brimstone, as God brought upon Sodom and Gomorrah. (Tosefta Taanit 2:13)

The Mishnah taught that the rainbow (of Genesis 9:13) was one of ten miraculous things that God created on the sixth day of creation at twilight on the eve of the Sabbath. (Avot 5:6) Rabbi Jose and Rabbi Judah disagreed whether verses of remembrance referring to the rainbow (Genesis 9:15–16) needed to be said together or individually. (Tosefta Rosh Hashanah 2:14)

The Drunkenness of Noah (painting by Michelangelo)

The Gemara helped explain why (as Genesis 9:13 reports) God chose a rainbow as the symbol of God's promise. The Mishnah taught with regard to those who take no thought for the honor of their Maker, that it would have been better if they had not been born. (Mishnah Chagigah 2:1; Babylonian Talmud Chagigah 11b.) Rabbi Abba read this Mishnah to refer to those who stare at a rainbow, while Rav Joseph said that it refers to those who commit transgressions in secret. The Gemara explained that those who stare at a rainbow affront God's honor, as Ezekiel 1:28 compares God's appearance to that of a rainbow: “As the appearance of the bow that is in the cloud in the day, so was the appearance of the brightness round about. This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.” Thus those who stare at a rainbow behave as if they were staring directly at God. (Babylonian Talmud Chagigah 16a.)

Noah's curse of Cain (engraving by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Bible in Pictures)

The Talmud deduced two possible explanations (attributed to Rav and Rabbi Samuel) for what Ham did to Noah to warrant Noah's curse of Canaan. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 70a.) According to one explanation, Ham castrated Noah, while the other says that Ham sexually abused Noah. The textual argument for castration goes this way: Since Noah cursed Ham by his fourth son Canaan, Ham must have injured Noah with respect to a fourth son, by emasculating him, thus depriving Noah of the possibility of a fourth son. The argument for abuse from the text draws an analogy between “and he saw” written in two places in the Bible: With regard to Ham and Noah, it was written, “And Ham the father of Canaan saw the nakedness of his father (Noah)”; while in Genesis 34:2, it was written, “And when Shechem the son of Hamor saw her (Dinah), he took her and lay with her and defiled her.” Thus this explanation deduced that similar abuse must have happened each time that the Bible uses the same language. (See also Genesis Rabbah 36:7; Leviticus Rabbah 17:5.)

Genesis chapter 10[]

A Baraita employed Genesis 10:6 to interpret the words “and Hebron was built seven years before Zoan in Egypt” in Numbers 13:22 to mean that Hebron was seven times as fertile as Zoan. The Baraita rejected the plain meaning of “built,” reasoning that Ham would not build a house for his younger son Canaan (in whose land was Hebron) before he built one for his elder son Mizraim (in whose land was Zoan, and Genesis 10:6 lists (presumably in order of birth) “the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Put, and Canaan.” The Baraita also taught that among all the nations, there was none more fertile than Egypt, for Genesis 13:10 says, “Like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt.” And there was no more fertile spot in Egypt than Zoan, where kings lived, for Isaiah 30:4 says of Pharaoh, “his princes are at Zoan.” And in all of Israel, there was no more rocky ground than that at Hebron, which is why the Patriarchs buried their dead there, as reported in Genesis 49:31. But rocky Hebron was still seven times as fertile as lush Zoan. (Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 112a.)

Rab and Samuel equated the Amraphel of Genesis 14:1 with the Nimrod whom Genesis 10:8 describes as “a mighty warrior on the earth,” but the two differed over which was his real name. One held that his name was actually Nimrod, and Genesis 14:1 calls him Amraphel because he ordered Abraham to be cast into a burning furnace (and thus the name Amraphel reflects the words for “he said” (amar) and “he cast” (hipil)). But the other held that his name was actually Amraphel, and Genesis 10:8 calls him Nimrod because he led the world in rebellion against God (and thus the name Nimrod reflects the word for “he led in rebellion” (himrid)). (Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 53a.)

The Tower of Babel (painting by Lucas van Valckenborch)

Genesis chapter 11[]

The Tosefta taught that the men of the Tower of Babel acted arrogantly before God only because God had been so good to them (in Genesis 11:1–2) as to give them a single language and allow them to settle in Shinar. And as usage elsewhere indicated that “settle” meant “eat and drink” (see Exodus 32:6), this eating and drinking was what led them to say (in Genesis 11:4) that they wanted to build the Tower. (Tosefta Sotah 3:10.)

The Confusion of Tongues (engraving by Gustave Doré from the 1865 La Sainte Bible)

Rabbi Levi, or some say Rabbi Jonathan, said that a tradition handed down from the Men of the Great Assembly taught that wherever the Bible employs the term “and it was” or “and it came to pass” (וַיְהִי, wa-yehi), as it does in Genesis 11:2, it indicates misfortune, as one can read wa-yehi as wai, hi, “woe, sorrow.” Thus the words, “And it came to pass,” in Genesis 11:2 are followed by the words, “Come, let us build us a city,” in Genesis 11:4. And the Gemara also cited the instances of Genesis 6:1 followed by Genesis 6:5; Genesis 14:1 followed by Genesis 14:2; Joshua 5:13 followed by the rest of Joshua 5:13; Joshua 6:27 followed by Joshua 7:1; 1 Samuel 1:1 followed by 1 Samuel 1:5; 1 Samuel 8:1 followed by 1 Samuel 8:3; 1 Samuel 18:14 close after 1 Samuel 18:9; 2 Samuel 7:1 followed by 1 Kings 8:19; Ruth 1:1 followed by the rest of Ruth 1:1; and Esther 1:1 followed by Haman. But the Gemara also cited as counterexamples the words, “And there was evening and there was morning one day,” in Genesis 1:5, as well as Genesis 29:10, and 1 Kings 6:1. So Rav Ashi replied that wa-yehi sometimes presages misfortune, and sometimes it does not, but the expression “and it came to pass in the days of” always presages misfortune. And for that proposition, the Gemara cited Genesis 14:1, Isaiah 7:1 Jeremiah 1:3, Ruth 1:1, and Esther 1:1. (Babylonian Talmud Megillah 10b.)

Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai taught that the report of Genesis 11:5 that “the Lord came down to see the city and the tower” was one of ten instances when the Torah reports that God descended. (Genesis Rabbah 38:9.)

The Dispersion (engraving by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld from the 1860 Bible in Pictures)

The Sages taught that the God who punished the generation of the Flood and the generation of the Dispersion would take vengeance on people who renege on their word after money has been paid. (Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:2; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 44a.)

The Gemara taught that Abraham asked God if God would ever punish Israel for its sins as God did to the generation of the Flood or the generation of the Dispersion, and God replied that God would not. God told Abraham that God had provided the order of sacrifices for Israel in the Torah, and whenever Jews read these passages, God would consider it as if they had offered the sacrifices, and God would pardon them for all their iniquities. (Babylonian Talmud Taanit 27b, Megillah 31b.)

The Gemara taught that Sarah was one of seven prophetesses who prophesied to Israel and neither took away from nor added anything to what is written in the Torah. (The other prophetesses were Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther.) The Gemara derived Sarah's status as a prophetess from the words, “Haran, the father of Milkah and the father of Yiscah,” in Genesis 11:29. Rabbi Isaac taught that Yiscah was Sarah. Genesis 11:29 called her Yiscah (יִסְכָּה) because she discerned (saketah) by means of Divine inspiration, as Genesis 21:12 reports God instructing Abraham, “In all that Sarah says to you, hearken to her voice.” Alternatively, Genesis 11:29 called her Yiscah because all gazed (sakin) at her beauty. (Babylonian Talmud Megillah 14a.)

Rav Nahman said in the name of Rabbah bar Abbuha that the redundant report, “And Sarai was barren; she had no child,” in Genesis 11:30 demonstrated that Sarah was incapable of procreation because she did not have a womb. (Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 64b.)

Commandments[]

Maimonides cited the parshah for one positive commandment:

- To "be fruitful and multiply" (Genesis 9:7)

(Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandment 212. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 1:228. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4.)

The Sefer ha-Chinuch, however, attributed the commandment to Genesis 1:28. (Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 1:82–85. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1991. ISBN 0-87306-515-8.)

Isaiah (painting by Michelangelo)

Haftarah[]

The haftarah for the parshah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews, Yemenite Jews, and Maghrebim: Isaiah 54:1–55:5

- for Sephardi Jews: Isaiah 55:1–10

- for some Yemenite communities: Isaiah 54:1–55:3

- for Italian Jews: Isaiah 54:1–55:5

- for Karaite Jews: Isaiah 54:9–55:12

- for Frankfurt am Main and Chabad Lubavitch: Isaiah 54:1–10

Connection to the Parshah[]

The parshah and haftarah both tell the power of God's covenant. The parshah (in Genesis 6:18 and Genesis 9:8-11) and the haftarah (in Isaiah 54:9–10) both report God's covenant with Noah never again to destroy the earth by flood. In the parshah (in Genesis 6:13) and the haftarah (in Isaiah 54:7–8), God confesses to anger at human transgression. In the wake of God's punishment, Genesis 9:11,15 and Isaiah 54:10 and 55:3 all use the words “no . . . more” (lo’ ‘od). The “righteousness” of Israel’s children in Isaiah 54:14 echoes that Noah is “righteous” in his age in Genesis 6:9.

In the liturgy[]

God’s dominion over the flood in Genesis 7:6–8:14 is reflected in Psalm 29:10, which is in turn recited as the Torah is returned to the Ark at the end of the Shabbat Torah service. (Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 153. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.)

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient[]

Gilgamesh tablet

- Atra-Hasis. Mesopotamia, 18th Century B.C.E. In, e.g., W.G. Lambert and A.R. Millard, Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1999. ISBN 1-57506-039-6

- Epic of Gilgamesh tablet 11. Mesopotamia, 14th–11th Century B.C.E. In e.g. James B. Pritchard. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 93–95. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-691-03503-2.

Biblical[]

- Genesis 1:28 (to be fruitful); 19:23–29 (God’s destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah); 35:11&src=! 35:11 (to be fruitful).

- Exodus 12:29–30(God’s destruction of Egypt’s firstborn).

- Isaiah 54:9–10.

- Jeremiah 18:1–10; 23:3.

- Ezekiel 9:4–6 (God’s destruction of Jerusalem’s sinners);14:20 (Noah as righteous intercessor).

Early nonrabbinic[]

- The Book of Noah. Jerusalem, early 2nd Century B.C.E.

- The Genesis Apocryphon. Dead Sea scroll 1Q20. Land of Israel, 1st Century B.C.E. Reprinted in Géza Vermes. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, 448, 450–53. New York: Penguin Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7139-9131-3.

Josephus

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 1:3:2–3, 5, 7–8, 4:1, 6:1, 3–5. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 32–38. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Qur'an 3:33–34; 4:163; 6:84; 7:59–64; 9:70; 71:1–28. Arabia, 7th Century.

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Sanhedrin 10:3; Avot 3:14, 5:6. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Demai 2:24; Shabbat 17:19; Rosh Hashanah 1:3, 2:14; Taanit 2:13; Yevamot 8:7; Sotah 3:6–10, 4:11, 10:3; Bava Kamma 9:31; Sanhedrin 13:6–7; Avodah Zarah 8:4–6. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifra 34:1, 4; 35:2; 93:1; 99:5; 108:2; 109:3; 243:1. Land of Israel, 4th Century C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:211, 214–15, 219; 2:87, 134, 173, 178; 3:286. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. Vol. 1 ISBN 1-55540-205-4. Vol. 2 ISBN 1-55540-206-2. Vol. 3 ISBN 1-55540-207-0.

Talmud

- Jerusalem Talmud: Berakhot 40a, 45a. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vol. 1. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2005.

- Genesis Rabbah 30:1–38:14. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Leviticus Rabbah 17:5. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 25b, 40a; Shabbat 31b, 109a, 113b, 137a, 150a, 151b; Eruvin 18a–b, 53a, 65a; Pesachim 3a, 54a; Yoma 9b–10a, 52b, 75a, 76a, 85a; Sukkah 52a; Rosh Hashanah 10b, 11b–12a; Taanit 19a, 27b; Megillah 9b, 14a, 17a; Moed Katan 25b; Chagigah 12a, 16a; Yevamot 62a, 63b, 64b; Ketubot 8a, 77b, 112a; Sotah 34b, 45b; Kiddushin 13a, 30b; Bava Kamma 91b; Bava Metzia 44a, 106b; Bava Batra 16b, 74a; Sanhedrin 17a, 24a, 38b, 44a, 56a–57b, 58b–59b, 69b–70a, 72b, 84b, 91a, 100b, 108a–09a; Makkot 8b, 11a; Shevuot 36a; Avodah Zarah 5a–6a, 11b, 19a, 23b, 51a; Horayot 13a; Zevachim 108b, 113b, 115b–16a; Chullin 23a, 89a, 102a, 139b; Bekhorot 46b, 57a; Temurah 28b; Keritot 6b; Meilah 16a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Rashi

Medieval[]

- Rashi. Commentary. Genesis 6–11. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 1:65–114. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-89906-026-9.

- Zohar 59b–76b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern[]

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:34, 38. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 430–31, 486. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

- “Mary Don't You Weep.” United States, 19th Century.

Dickinson

- Emily Dickinson. Poem 48 (Once more, my now bewildered Dove). Circa 1858. Poem 403 (The Winters are so short —). Circa 1862. Poem 1473 (We talked with each other about each other). Circa 1879. In The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, 27, 192, 623. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-18414-4.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 5, 8–12, 15–16, 19–24, 35–36, 64, 68, 71, 73, 88–89, 107, 109, 154, 172, 183, 323–24, 333, 337, 339–41, 347, 355, 441–42, 447–48, 515, 547, 604–05, 715, 783, 806, 926. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- Jay Macpherson. The Boatman. Oxford Univ. Press Canada, 1957.

- James Baldwin. The Fire Next Time. 1963. Reprinted Modern Library, 1995. ISBN 0679601511.

- Marc Gellman. Does God Have a Big Toe? Stories About Stories in the Bible, 27–45. New York: HarperCollins, 1989. ISBN 0-06-022432-0.

- Mario Brelich. Navigator of the Flood. Marlboro, Vermont: Marlboro Press, 1991. ISBN 0-910395-80-2.

- Elie Wiesel. “Noah.” In Sages and Dreamers: Biblical, Talmudic, and Hasidic Portraits and Legends, 19–34. New York: Summit Books, 1991. ISBN 0-671-74679-0.

Wiesel

- Neal Stephenson. Snow Crash. New York: Bantam Spectra, 1992. ISBN 0-553-08853-X.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel, 5. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993. ISBN 1-56000-081-3.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Bible Versus Babel: Why did God tell Abraham to leave Mesopotamia, the most advanced civilization of its time, for the backwater region of Canaan?” Bible Review. 11 (2) (Apr. 1995).

- Karen Armstrong. In the Beginning: A New Interpretation of Genesis, 39–53. New York: Knopf, 1996. ISBN 0-679-45089-0.

- Norman Cohn. Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1996. ISBN 0-300-06823-9.

- Marc Gellman. God's Mailbox: More Stories About Stories in the Bible, 24–29, 107–11. New York: Morrow Junior Books, 1996. ISBN 0-688-13169-7.

- Jacob Migrom. “The Blood Taboo: Blood should not be ingested because it contains life. Whoever does so is guilty of murder.” Bible Review. 13 (4) (Aug. 1997).

Steinsaltz

- Adin Steinsaltz. Simple Words: Thinking About What Really Matters in Life, 49. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. ISBN 068484642X.

- Joseph Telushkin. The Ten Commandments of Character: Essential Advice for Living an Honorable, Ethical, Honest Life, 87–91, 275–78. New York: Bell Tower, 2003. ISBN 1-4000-4509-6.

- David Maine. The Preservationist. St. Martin's Press, 2004. ISBN 0-312-32847-8.

- Kacy Barnett-Gramckow. The Heavens Before. Chicago: Moody, 2004. ISBN 0-8024-1363-3.

- Kacy Barnett-Gramckow. He Who Lifts the Skies. Chicago: Moody, 2004. ISBN 0-8024-1368-4.

- Kacy Barnett-Gramckow. A Crown in the Stars. Chicago: Moody, 2005. ISBN 0-8024-1369-2.

- Chris Adrian. The Children's Hospital. McSweeney's, 2006. ISBN 1932416609.

- Esther Jungreis. Life Is a Test, 168, 218–19, 229–30. Brooklyn: Shaar Press, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0609-0.

See also[]

- Noah in rabbinic literature

External links[]

Texts[]

Commentaries[]

- Academy for Jewish Religion, California

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- American Jewish University

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- Orthodox Union

- Parshah Parts

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Tanach Study Center

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

| |||||||||||||||||||

ru:Ноах (недельная глава) yi:פרשת נח