| Ajanta Caves* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | Template:Flag |

| Type | Cultural 1 |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 242 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

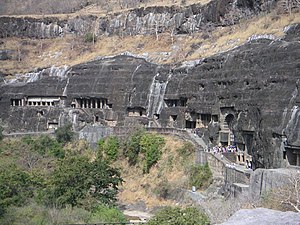

Ajanta Caves (Devanagari: अजंठा लेणी) in Maharashtra, India are rock-cut cave monuments dating from the second century BCE, containing paintings and sculpture considered to be masterpieces of both "Buddhist religious art"[1] and "universal pictorial art".[2] The caves are located just outside the village of Ajinṭhā in Aurangabad district in the Indian state of Maharashtra (N. lat. 20 deg. 30' by E. long. 75 deg. 40'). Since 1983, the Ajanta Caves have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A National Geographic[3] edition reads, "The flow between faiths was such that for hundreds of years, almost all Buddhist temples, including the ones at Ajanta, were built under the rule and patronage of Hindu kings."

Locality[]

Cave One[]

Cave 1

It is first approach and has no relation to the chronological sequence of the caves. It is the first cave on the eastern end of the horse-shoe shaped scarp. According to Spink, it is one of the latest caves to have begun on site and brought to near-completion in the Vākāţaka phase. Although there is no epigraphic evidence, it has been proposed that the Vākāţaka king Harisena may have been the benefactor of this better-preserved cave. A dominant reason for this is that Harisena was not involved initially in patronizing Ajanta.

This cave has one of the most elaborate carvings on its facade with relief sculptures on entablature and ridges. There are scenes carved from the life of the Buddha as well as a number of decorative motifs. A two pillared portico, visible in the 19th-century photographs, has since perished. The cave has a front-court with cells fronted by pillared vestibules on either side. These have a high plinth level. The cave has a porch with simple cells on both ends. The absence of pillared vestibules on the ends suggest that the porch was not excavated in the latest phase of Ajanta when pillared vestibules had become a necessity and norm. Most areas of the porch were once covered with murals, of which many fragments remain. There are three doorways: a central doorway and two side doorways. Two square windows were carved between the doorways to brighten the interiors.

Each wall of the hall inside is nearly 40 feet (12 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Twelve pillars make a square colonnade inside supporting the ceiling, and creating spacious aisles along the walls. There is a shrine carved on the rear wall to house an impressive seated image of the Buddha, his hands being in the dharmachakrapravartana mudra. There are four cells on each of the left, rear, and the right walls. The walls are covered with paintings in a fair state of preservation. The scenes depicted are mostly didactic, devotional, and ornamental. The themes are from the Jataka stories (the stories of the Buddha's former existences as Boddhisattva), the life of the Gautama Buddha, and those of his veneration.

Cave Two[]

Painting, Cave No. 2

Painting from the Ajanta caves

Ajanta Caves

Ajanta Caves

Cave 2, adjacent to Cave 1, is known for the paintings that have been preserved on its walls, ceilings, and pillars. It looks pretty much the same as Cave 1 and is in a better state of preservation. and it is a really important

The facade[]

Cave 2 has a porch quite different from Cave one. Even the facade carvings seem to be different. The cave is supported by robust pillars, ornamented with designs. The size and ground plan have many things in common with the first cave.

The porch[]

The front porch consists of cells supported by pillared vestibules on both ends. The cells on the previously "wasted areas" were needed to meet the greater housing requirements in later years. Porch-end cells became a trend in all later Vakataka excavations. The simple single cells on porch-ends were converted into CPVs or were planned to provide more room, symmetry, and beauty.

The paintings on the ceilings and walls of this porch have been widely published. They depict the Jataka tales that are stories of the Buddha's life in former existences as Bodhisattva. The porch's rear wall has a doorway in the center, which allows entrance to the hall. On either side of the door is a square-shaped window to brighten the interior

The hall[]

The hall has four colonnades supporting the ceiling and surrounding a square in the center of the hall. Each arm or colonnade of the square is parallel to the respective walls of the hall, making an aisle in between. The colonnades have rock-beams above and below them. The capitals are carved and painted with various decorative themes that include ornamental, human, animal, vegetative, and semi-divine forms.

The paintings[]

Paintings are all over the cave except for the floor. At various places the art work has become eroded due to decay and human interference. Therefore, many areas of the painted walls, ceilings, and pillars are fragmentary. The painted narratives of the Jataka tales are depicted only on the walls, which demanded the special attention of the devotee. They are didactic in nature, meant to inform the community about the Buddha's teachings and life through successive births. Their placement on the walls required the devotee to walk through the aisles and 'read' the narratives depicted in various episodes. (Alas, to prevent vandalism, entry into the aisles is restricted by site authorities). The narrative episodes are depicted one after another although not in a linear order. Their identification has been a core area of research since the site's rediscovery in 1819 C.E. Dieter Schlingloff's identifications have updated our knowledge on the subject.

For quite some time the art work was erroneously alluded to as "frescoes". We now know that the proper term for this kind of artwork is mural, because the known process and technique of fresco painting isn't found in this kind of artwork. At Ajanta, the technique and process used to produce this kind of artwork is unlike any other artwork found in the art history of other civilizations. These murals have a certain uniqueness about them, even within the history of South Asian art.

The process of painting involved several stages. The first step was to chisel the rock surface, to make it rough enough to hold the plaster. The plaster was made of clay, hay, dung and lime. Differences are found in the ingredients and their proportions from cave to cave. While the plaster was still wet, the drawings were done and the colors applied. The wet plaster had the capacity to soak the color so that the color became a part of the surface and would not peel off or decay easily. The colors were referred to as 'earth colors' or 'vegetable colors.' Various kinds of stones, minerals, and plants were used in combinations to prepare different colors. Sculptures were often covered with stucco to give them a fine finish and lustrous polish. The stucco had the ingredients of lime and powdered seashell or conch. The latter afforded exceptional shine and smoothness. In cave upper six, some of it is extant. The smoothness resembles the surface of glass. The paint brushes used to create the artwork were made from animal hair and twigs.

Rediscovery by Europeans[]

By AD 480 the caves at Ajanta were abandoned. During the next 1300 years the jungle grew back and the caves were hidden, unvisited and undisturbed until the Spring of 1819 when a British officer in the Madras army entered the steep gorge on the trail of a tiger. Somehow, deep within the tangled undergrowth, he came across the almost hidden entrance to one of the caves. Exploring that first cave, long since a home to nothing more than birds and bats and a lair for other, larger, animals, Captain Smith wrote his name in pencil on one of the walls. Still faintly visible, it records his name and the date, April 1819.

How to get there[]

You can fly to Aurangabad and then take a car from your hotel to the caves (about 100 km away) as well as to Ellora caves (30 km from Aurangabad) and Daulatabad fort. The cars have to drop you at the base of the hill and you have to take a bus up to the caves entrance. The bus is run by the State Transport corporation and is not much more than basic. The fare is Rs. 7. You can climb up the 4km to the caves, but go in a group and remember the heat of the sun! You need to queue quite a bit to get the bus (too few buses, too many tourists).

At the car park there are hordes of hawkers and shops that sell kitschy, over-priced junk for tourists. These hawkers and those selling books at the caves can be quite pushy and persistent towards foreign tourists.

At the caves entrance, you have to buy tickets for the caves -- Rs. 250 for foreigners and Rs. 10 for Indian citizens/PIOs/OCIs. You can buy a reasonably priced, government guide book from the ticket counter for Rs. 100.

You then have to climb up to get to the caves. At the entrance, you are told that you need to not wear your shoes. This is not true for all the caves and definitely not true for the distance between the caves. This is a ploy to get you to hire a porter for Rs. 150 to carry your shoes. You're better off carrying it on your own.

See also[]

| Pilgrimage to Buddha's Holy Sites |

|

| The Four Main Sites |

|---|

| Lumbini · Bodh Gaya Sarnath · Kushinagar |

| Four Additional Sites |

| Sravasti · Rajgir Sankissa · Vaishali |

| Other Sites |

| Patna · Gaya · Kosambi Kapilavastu · Devadaha Kesariya · Pava Nalanda · Vikramshila · Varanasi |

| Later Sites |

| Sanchi · Mathura Ellora · Ajanta |

- Barabar Caves

- Elephanta Caves

- Ellora Caves

References[]

Literature[]

- Burgess, James and Fergusson J. Cave Temples of India. (London: W.H. Allen & Co., 1880. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd., Delhi, 2005). ISBN 8121502519

- Burgess, James, and Indraji, Bhagwanlal. Inscriptions from the Cave Temples of Western India, Archaeological Survey of Western India, Memoirs, 10 (Bombay: Government Central Press, 1881).

- Burgess, James. Buddhist Cave Temples and Their Inscriptions, Archaeological Survey of Western India, 4 (London: Trubner & Co., 1883; Varanasi: Indological Book House, 1964).

- Burgess, James. “Notes on the Bauddha Rock Temples of Ajanta, Their Paintings and Sculptures,” Archaeological Survey of Western India, 9 (Bombay: Government Central Press, 1879).

- Behl, Benoy K. The Ajanta Caves (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998).

- Cohen, Richard Scott. Setting the Three Jewels: The Complex Culture of Buddhism at the Ajanta Caves. A Ph.D. dissertation (Asian Languages and Cultures: Buddhist Studies, University of Michigan, 1995).

- Cowell, E.B. The Jataka, I-VI (Cambridge: Cambridge, 1895; reprint, 1907).

- Dhavalikar, M.K. Late Hinayana Caves of Western India (Pune: 1984).

- Griffiths, J. Paintings in the Buddhist Cave Temples of Ajanta, 2 vols. (London: 1896 - 1897).

- Kramrisch, Stella. A Survey of Painting in the Deccan (Calcutta and London: The India Society in co-operation with the Dept. of Archaeology, 1937). Reproduced: “Ajanta,” Exploring India’s Sacred Art: Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch, ed. Miller, Barbara Stoler (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press: 1983), pp. 273–307; reprint (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1994), pp. 273–307.

- Majumdar, R.C. and A.S. Altekar, eds. The Vakataka-Gupta Age. New History of Indian People Series, VI (Benares: Motilal Banarasidass, 1946; reprint, Delhi: 1960).

- Mirashi, V.V. “Historical Evidence in Dandin’s Dasakumaracharita,” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 24 (1945), 20ff. Reproduced: Studies in Indology, 1 (Nagpur: Vidarbha Samshodhan Mandal, 1960), pp. 164–77.

- Mirashi, V.V. Inscription of the Vakatakas. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Series, 5 (Ootacamund: Government Epigraphist for India, 1963).

- Mirashi, V.V. The Ghatotkacha Cave Inscriptions with a Note on Ghatotkacha Cave Temples by Srinivasachar, P. (Hyderabad: Archaeological Department, 1952).

- Mirashi, V.V. Vakataka inscription in Cave XVI at Ajanta. Hyderabad Archaeological Series, 14 (Calcutta: Baptist mission Press for the Archaeological Department of His Highness the Nizam's Dominions, 1941).

- Mitra, Debala. Ajanta, 8th ed. (Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1980).

- Nagaraju, S. Buddhist Architecture of Western India (Delhi: 1981).

- Parimoo, Ratan; et al. The Art of Ajanta: New Perspectives, 2 vols (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1991).

- Schligloff, Dieter. Guide to the Ajanta Paintings, vol. 1; Narrative Wall Paintings (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999)

- Schligloff, Dieter. Studies in the Ajanta Paintings: Identifications and Interpretations (New Delhi: 1987).

- Shastri, Ajay Mitra, ed. The Age of the Vakatakas (New Delhi: Harman, 1992).

- Spink, Walter M. “A Reconstruction of Events related to the development of Vakataka caves,” C.S. Sivaramamurti felicitation volume, ed. M.S. Nagaraja Rao (New Delhi: 1987).

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Chronology: Cave 1’s Patronage,” Chhavi 2, ed. Krishna, Anand (Benares: Bharat Kala Bhawan, 1981), pp. 144–57.

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Chronology: Cave 7’s Twice-born Buddha,” Studies in Buddhist Art of South Asia, ed. Narain, A.K. (New Delhi: 1985), pp. 103–16.

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Chronology: Politics and Patronage,” Kaladarsana, ed. Williams, Joanna (New Delhi: 1981), pp. 109–26.

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Chronology: The Crucial Cave,” Ars Orientalis, 10 (1975), pp. 143–169.

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Chronology: The Problem of Cave 11,” Ars Orientalis, 7 (1968), pp. 155–168.

- Spink, Walter M. “Ajanta’s Paintings: A Checklist for their Dating,” Dimensions of Indian Art, Pupul Jayakar Felicitation Volume, ed. Chandra, Lokesh; and Jain, Jyotindra (Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1987), p. 457.

- Spink, Walter M. “Notes on Buddha Images,” The Art of Ajanta: New Perspectives, vol. 2, ed. Parimoo, Ratan, et al. (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1991), pp. 213–41.

- Spink, Walter M. “The Achievement of Ajanta,” The Age of the Vakatakas, ed. Shastri, Ajaya Mitra (New Delhi: Harman Publishing House, 1992), pp. 177–202.

- Spink, Walter M. “The Vakataka’s Flowering and Fall,” The Art of Ajanta: New Perspectives, vol. 2, ed. Parimoo, Ratan, et al. (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1991), pp. 71–99.

- Spink, Walter M. “The Archaeology of Ajanta,” Ars Orientalis, 21, pp. 67–94.

- Weiner, Sheila L. Ajanta: It’s Place in Buddhist Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1977).

- Yazdani, Gulam. Ajanta: the Colour and Monochrome Reproductions of the Ajanta Frescoes Based on Photography, 4 vols. (London: Oxford University Press, 1930 [31?], 1955).

- Yazdani, Gulam. The Early History of the Deccan, Parts 7-9 (Oxford: 1960).

- Zin, Monika. Guide to the Ajanta Paintings, vol. 2; Devotional and Ornamental Paintings (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2003).

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ajanta Caves |

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- A delightful essay on Ajanta Caves from the online travel magazine travelmag.co.uk (May 10, 2009)

- Video of the caves MTDC site

- Ajanta Caves in UNESCO List

- "Ajanta", Jacques-Edouard Berger Foundation, World Art Treasures (choose French or English)

- Frontline Article On Ajanta Paintings

- Photographs of the Ajanta caves-paintings and sculpture, IndiaMonuments.org

- Article on Ajanta from the Travel section of the New York Times (November 5, 2006)

- photos of the Ajanta caves

- Photographs

- Video Travelogue on Ajanta Cave Temples

Template:World Heritage Sites in India

Coordinates: 20°32′01″N 75°44′59″E / 20.53361°N 75.74972°E

ar:أجانتا bn:অজন্তা গুহাসমূহ ca:Ajanta cs:Adžanta da:Ajanta Caves gu:અજંતાની ગુફાઓ ko:아잔타 석굴 hi:अजंता गुफाएं hr:Špiljski hramovi u Ajanti kn:ಅಜಂತಾ lt:Adžantos olos ml:അജന്ത ഗുഹകള് mr:अजिंठा-वेरूळची लेणी ja:アジャンター石窟群 pt:Grutas de Ajanta ro:Ajanta ru:Аджанта sk:Adžanta fi:Ajanta sv:Ajantagrottorna ta:அஜந்தா ஓவியங்கள் te:అజంతా గుహలు uk:Аджанта vi:Chùa hang Ajanta zh:阿旖陀石窟