Acharei, Achrei Mos, Aharei Mot, or Ahare Moth (אחרי or אחרי מות — Hebrew for “after” or “after the death,” the fifth word or fifth and sixth words, and the first distinctive word or words, in the parshah) is the 29th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the sixth in the book of Leviticus. It constitutes Leviticus 16:1–18:30. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in April or early May.

The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 54 weeks, the exact number varying between leap years and regular years. In years with 54 weeks (for example, 2008, 2011, and 2014), parshah Acharei is read separately on the 29th Sabbath after Simchat Torah. In years with fewer than 54 weeks (for example, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015), parshah Acharei is combined with the subsequent parshah, Kedoshim, to help achieve the needed number of weekly readings.

Traditional Jews also read parts of the parshah as Torah readings for Yom Kippur. Leviticus 16 is the traditional Torah reading for the Yom Kippur morning (Shacharit) service, and Leviticus 18 is the traditional Torah reading for the Yom Kippur Minchah service. Some Conservative congregations substitute readings from Leviticus 19 for the traditional Leviticus 18 in the Yom Kippur Minchah service. (See Mahzor for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Edited by Jules Harlow. United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. ISBN 0874411483.) And in the standard Reform prayerbook for the High Holidays (machzor), Deuteronomy 29:9–14 and 30:11–20 are the Torah readings for the morning Yom Kippur service, in lieu of the traditional Leviticus 16. (Gates of Repentance: The New Union Prayerbook for the Days of Awe. Edited by Chaim Stern, 342–45. New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis, Revised ed. 1996. ISBN 0-88123-069-3.)

The Scapegoat (painting by William Holman Hunt)

Summary[]

Yom Kippur[]

The text tells the ritual of Yom Kippur. After the death of Aaron’s sons, God told Moses to tell Aaron not to come at will into the Most Holy Place (the Kodesh Hakodashim), lest he die, for God appeared in the cloud there. (Leviticus 16:1–2.) Aaron was to enter only after bathing in water, dressing in his sacral linen tunic, breeches, sash, and turban, and bringing a bull for a sin offering, two rams for burnt offerings, and two he-goats for sin offerings. (Leviticus 16:3–5.) Aaron was to take the two goats to the entrance of the Tabernacle and place lots upon them, one marked for the Lord and the other for Azazel. (Leviticus 16:7–8.) Aaron was to offer the goat designated for the Lord as a sin offering, and to send off to the wilderness the goat designated for Azazel. (Leviticus 16:9–10.) Aaron was then to offer the bull of sin offering. (Leviticus 16:11.) Aaron was then to take a pan of glowing coals from the altar and two handfuls of incense and put the incense on the fire before the Most Holy Place, so that the cloud from the incense would screen the Ark of the Covenant. (Leviticus 16:12–13.) He was to sprinkle some of the bull’s blood and then some of the goat’s blood over and in front of the Ark, to purge the Shrine of the uncleanness and transgression of the Israelites. (Leviticus 16:14–16.) He was then to apply some of the bull’s blood and goat’s blood to the altar, to cleanse and consecrate it. (Leviticus 16:17–19.)

one imagining of Azazel (from Colin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal)

Aaron was then to lay his hands on the head of the live goat, confess over it the Israelites’ sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and then through a designated man send it off to the wilderness to carry their sins to an inaccessible region. (Leviticus 16:21–22.) Then Aaron was to go into the Tabernacle, take off his linen vestments, bathe in water, put on his vestments, and then offer the burnt offerings. (Leviticus 16:23–25.) The one who set the Azazel-goat free was to wash his clothes and bathe in water. (Leviticus 16:26.) The bull and goat of sin offering were to be taken outside the camp and burned, and he who burned them was to wash his clothes and bathe in water. (Leviticus 16:27–28.)

The text then commands this law for all time: On the tenth day of the seventh month, Jews and aliens who reside with them were to practice self-denial and do no work. (Leviticus 16:29.) On that day, the High Priest was to put on the linen vestments, purge the Tabernacle, and make atonement for the Israelites once a year. (Leviticus 16:30–34.)

Centralized offerings and blood[]

The text next begins what scholars call the Holiness Code. God prohibited Israelites from slaughtering oxen, sheep, or goats without bringing them to the Tabernacle as an offering, on pain of exile. (Leviticus 17:1–9.) God prohibited consuming blood. (Leviticus 17:10–12.) One who hunted an animal for food was to pour out its blood and cover it with earth. (Leviticus 17:13.) Anyone who ate what had died or had been torn by beasts was to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and remain unclean until evening. (Leviticus 17:15–16.)

Sexual practices[]

God prohibited any Israelite from uncovering the nakedness of his father, mother, father's wife, sister, grandchild, half-sister, aunt, daughter-in-law, or sister-in-law. (Leviticus 18:1–16.) A man could not marry a woman and her daughter, a woman and her granddaughter, or a woman and her sister during the other's lifetime. (Leviticus 18:17–18.) A man could not cohabit with a woman during her period or with his neighbor's wife. (Leviticus 18:19–20.) Israelites were not to allow their children to be offered up to Molech. (Leviticus 18:21.) A man could not lie with a man as with a woman. (Leviticus 18:22.) God prohibited bestiality. (Leviticus 18:23.) God explained that the Canaanites defiled themselves by adopting these practices, and any who did any of these things would be cut off from their people. (Leviticus 18:24–30.)

The Temple in Jerusalem

In inner-biblical interpretation[]

Leviticus chapter 17[]

Deuteronomy 12:1–28, like Leviticus 17:1–10, addresses the centralization of sacrifices and the permissibility of eating meat. While Leviticus 17:3–4 prohibited killing an ox, lamb, or goat (each a sacrificial animal) without bringing it to the door of the Tabernacle as an offering to God, Deuteronomy 12:15 allows killing and eating meat in any place.

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Leviticus chapter 16[]

Rabbi Joshua of Siknin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the Evil Inclination criticizes four laws as without logical basis, and Scripture uses the expression “statute” (chuk) in connection with each: the laws of (1) a brother's wife (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), (2) mingled kinds (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), (3) the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16), and (4) the red cow (in Numbers 19). (Numbers Rabbah 19:5.)

Tractate Yoma in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11. (Mishnah Yoma 1:1–8:9; Tosefta Kippurim (Yoma) 1:1–4:17; Jerusalem Talmud Yoma 1a–; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 2a–88a.)

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13. (Mishnah Beitzah 1:1–5:7; Tosefta Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11; Jerusalem Talmud Beitzah 1a–; Babylonian Talmud Beitzah 2a–40b.)

High Priest Offering Incense on the Altar (illustration from Henry Davenport Northrop. Treasures of the Bible. International Pub. Co., 1894.)

The Mishnah taught that during the days of the Temple, seven days before Yom Kippur, they would move the High Priest from his house to the cell of the counselors and prepare another priest to take his place in case anything impure happened to him to make him unfit to perform the service. Rabbi Judah said that they prepared another wife for him, in case his wife should die, as Leviticus 16:6 says that “he shall make atonement for himself and for his house” and “his house” means “his wife.” But they told Rabbi Judah that if they would do so, then there would be no end to the matter, as they would have to prepare a third wife in case the second died, and so on. (Mishnah Yoma 1:1; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 2a.) The rest of the year, the High Priest would offer sacrifices only if he wanted to, but during the seven days before Yom Kippur, he would sprinkle the blood of the sacrifices, burn the incense, trim the lamps, and offer the head and the hind leg of the sacrifices. (Mishnah Yoma 1:2; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 14a.) They brought sages from the court to the High Priest, and throughout the seven days they read to him about the order of the service. They asked the High Priest to read it aloud, in case he had forgotten or never learned. (Mishnah Yoma 1:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 18a.)

On the morning of the day before Yom Kippur, they placed the High Priest at the Eastern Gate and brought before him oxen, rams, and sheep, so that he could become familiar with the service. (Mishnah Yoma 1:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 18a.) The rest of the seven days, they did not withhold food or drink from him, but near nightfall on the eve of Yom Kippur, they would not let him eat much, as food might make him sleep. (Mishnah Yoma 1:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 18a.) The sages of the court took him up to the house of Avtinas and handed him over to the elders of the priesthood. As the sages of the court took their leave, they cautioned him that he was the messenger of the court, and adjured him in God's Name that he not change anything in the service from what they had told him. He and they turned aside and wept that they should have to suspect him of doing so. (Mishnah Yoma 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 18b.)

The High Priest

On the night before Yom Kippur, if the High Priest was a sage, he would expound the relevant Scriptures, and if he was not a sage, the disciples of the sages would expound before him. If he was used to reading the Scriptures, he would read, and if he was not, they would read before him. They would read from Job, Ezra, and Chronicles, and Zechariah ben Kubetal said from Daniel. (Mishnah Yoma 1:6; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 18b.) If he tried to sleep, young priests would snap their middle finger before him and say, “Mr. High Priest, arise and drive the sleep away!” They would keep him busy until near the time for the morning offering. (Mishnah Yoma 1:7; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 19b.)

On any other day, a priest would remove the ashes from the altar at about the time of the cock's crow (in accordance with Leviticus 6:3). But for Yom Kippur, the ashes were removed beginning at midnight of the night before. Before the cock's crow approached, Israelites filled the Temple Court. (Mishnah Yoma 1:8; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 20a.) The officer told the priests to see whether the time for the morning sacrifice had arrived. If it had, then the priest who saw it would call out, “It’s daylight!” (Mishnah Yoma 3:1; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 28a.)

They led the High Priest down to the place of immersion (the mikvah). (Mishnah Yoma 3:2; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 28a.) During the day of Yom Kippur, the High Priest would immerse himself five times and wash his hands and feet ten times. Except for this first immersion, he would do each on holy ground in the Parwah cell. (Mishnah Yoma 3:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 30a.) They spread a linen sheet between him and the people. (Mishnah Yoma 3:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 30a.) If the High Priest was either old or delicate, they warmed the water for him. (Mishnah Yoma 3:5; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 31b.) He undressed, immersed himself, came up, and dried off. They brought him the golden garments; he put them on and washed his hands and feet. (Mishnah Yoma 3:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 31b.)

They brought him the continual offering; he cut its throat, and another priest finished slaughtering it. The High Priest received the blood and sprinkled it on the altar. He entered the Sanctuary, burned the morning incense, and trimmed the lamps. Then he offered up the head, limbs, cakes, and wine-offering. (Mishnah Yoma 3:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 31b.)

They brought him to the Parwah cell, spread a sheet of linen between him and the people, he washed his hands and feet, and undressed. (Rabbi Meir said that he undressed first and then washed his hands and feet.) Then he went down and immersed himself for the second time, came up and dried himself. They brought him white garments (as required by Leviticus 16:4). He put them on and washed his hands and feet. (Mishnah Yoma 3:6; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 34b.) Rabbi Meir taught that in the morning, he wore Pelusium linen worth 12 minas, and in the afternoon he wore Indian linen worth 800 zuz. But the sages said that in the morning, he wore garments worth 18 minas, and in the afternoon he wore garments worth 12 minas. The community paid for these sums, and the High Priest could spend more from his own funds if he wanted to. (Mishnah Yoma 3:7; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 34b.)

Rav Hisda asked why Leviticus 16:4 instructed the High Priest to enter the inner precincts (the Kodesh Hakodashim) to perform the Yom Kippur service in linen vestments instead of gold. Rav Hisda taught that it was because the accuser may not act as defender. Gold played the accuser because it was used in the Golden Calf, and thus gold was inappropriate for the High Priest when he sought atonement and thus played the defender. (Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 26a.)

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest came to his bull (as required in Leviticus 16:3 & 6), which was standing between the hall and the altar with its head to the south and its face to the west. The High Priest stood on the east with his face to the west. And he pressed both his hands on the bull and made confession, saying: “O Lord! I have done wrong, I have transgressed, I have sinned before You, I and my house. O Lord! Forgive the wrongdoings, the transgressions, and the sins that I have committed, transgressed, and sinned before You, I and my house, as it is written in the Torah of Moses Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): “For on this day shall atonement be made for you to cleanse you; from all your sins shall you be clean before the Lord.” And the people answered: “Blessed is the Name of God’s glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!” (Mishnah Yoma 3:8; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 35b.)

The High Priest then went back to the east of the Temple Court, north of the altar. The two goats required by Leviticus 16:7 were there, as was an urn containing two lots. The urn was originally made of boxwood, but Ben Gamala remade them in gold, earning him praise. (Mishnah Yoma 3:9; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 37a.) Rabbi Judah explained that Leviticus 16:7 mentioned the two goats equally because they should be alike in color, height, and value. (Babylonian Talmud Shevuot 13b.) The Mishnah taught that the High Priest shook the urn and brought up the two lots. On one lot was inscribed “for the Lord,” and on the other “for Azazel.” The Deputy High Priest stood at the High Priest's right hand and the head of the ministering family at his left. If the lot inscribed “for the Lord” came up in his right hand, the Deputy High Priest would say “Mr. High Priest, raise your right hand!” And if the lot inscribed “for the Lord” came up in his left hand, the head of the family would say “Mr. High Priest, raise your left hand!” Then he placed them on the goats and said: “A sin-offering ‘to the Lord!’” (Rabbi Ishmael taught that he did not need to say “a sin-offering” but just “to the Lord.”) And then the people answered “Blessed is the Name of God’s glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!” (Mishnah Yoma 4:1; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 39a.)

Then the High Priest bound a thread of crimson wool on the head of the Azazel goat, and placed it at the gate from which it was to be sent away. And he placed the goat that was to be slaughtered at the slaughtering place. He came to his bull a second time, pressed his two hands on it and made confession, saying: “O Lord, I have dealt wrongfully, I have transgressed, I have sinned before You, I and my house, and the children of Aaron, Your holy people, o Lord, pray forgive the wrongdoings, the transgression, and the sins that I have committed, transgressed, and sinned before You, I and my house, and the children of Aaron, Your holy people. As it is written in the Torah of Moses, Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): ‘For on this day atonement be made for you, to cleanse you; from all the sins shall you be clean before the Lord.’” And then the people answered: “Blessed is the Name of God’s glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!” (Mishnah Yoma 4:2; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b.) Then he killed the bull. (Mishnah Yoma 4:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 43b.)

Rabbi Isaac noted two red threads, one in connection with the red cow in Numbers 19:6, and the other in connection with the scapegoat in the Yom Kippur service of Leviticus 16:7–10 (which Mishnah Yoma 4:2 indicates was marked with a red thread). Rabbi Isaac had heard that one required a definite size, while the other did not, but he did not know which was which. Rav Joseph reasoned that because (as Mishnah Yoma 6:6 explains) the red thread of the scapegoat was divided, that thread required a definite size, whereas that of the red cow, which did not need to be divided, did not require a definite size. Rami bar Hama objected that the thread of the red cow required a certain weight (to be cast into the flames, as described in Numbers 19:6). Raba said that the matter of this weight is disputed by Tannaim. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b.)

High Priest Offering a Sacrifice of a Goat (illustration from Henry Davenport Northrop. Treasures of the Bible. International Pub. Co., 1894.)

When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel, he said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that there were three red threads: one in connection with the red cow, the second in connection with the scapegoat, and the third in connection with the person with skin disease (the m’tzora) in Leviticus 14:4. Rav Dimi reported that one weighed ten zuz, another weighed two selas, and the third weighed a shekel, but he could not say which was which. When Rabin came, he said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the thread in connection with the red cow weighed ten zuz, that of the scapegoat weighed two selas, and that of the person with skin disease weighed a shekel. Rabbi Johanan said that Rabbi Simeon ben Halafta and the Sages disagreed about the thread of the red cow, one saying that it weighed ten shekels, the other that it weighed one shekel. Rabbi Jeremiah of Difti said to Rabina that they disagreed not about the thread of the red cow, but about that of the scapegoat. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b–42a.)

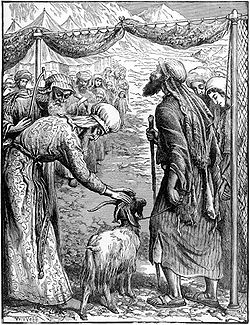

Sending Out the Scapegoat (illustration by William James Webb)

One would bring the High Priest the goat to be slaughtered, he would kill it, receive its blood in a basin, enter again the Sanctuary, and would sprinkle once upwards and seven times downwards. He would count: “one,” “one and one,” “one and two,” and so on. Then he would go out and place the vessel on the second golden stand in the sanctuary. (Mishnah Yoma 5:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 53b.)

Then the High Priest came to the scapegoat and laid his two hands on it, and he made confession, saying: “I beseech You, o Lord, Your people the house of Israel have failed, committed iniquity and transgressed before you. I beseech you, o Lord, atone the failures, the iniquities and the transgressions that Your people, the house of Israel, have failed, committed, and transgressed before you, as it is written in the Torah of Moses, Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): ‘For on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you; from all your sins shall you be clean before the Lord.’” And when the Priests and the people standing in the Temple Court heard the fully-pronounced Name of God come from the mouth of the High Priest, they bent their knees, bowed down, fell on their faces, and called out: “Blessed is the Name of God’s glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!” (Mishnah Yoma 6:2; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 66a.)

They handed the scapegoat over to him who was to lead it away. All were permitted to lead it away, but the Priests made it a rule not to permit an ordinary Israelite to lead it away. Rabbi Jose said that Arsela of Sepphoris once led it away, although he was not a priest. (Mishnah Yoma 6:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 66a.) The people went with him from booth to booth, except the last one. The escorts would not go with him up to the precipice, but watched from a distance. (Mishnah Yoma 6:5; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 67a.) The one leading the scapegoat divided the thread of crimson wool, and tied one half to the rock, the other half between the scapegoat horns, and pushed the scapegoat from behind. And it went rolling down and before it had reached half its way down the hill, it was dashed to pieces. He came back and sat down under the last booth until it grew dark. His garments unclean become unclean from the moment that he has gone outside the wall of Jerusalem, although Rabbi Simeon taught that they became unclean from the moment that he pushed it over the precipice. (Mishnah Yoma 6:6; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 67a.)

The Mishnah interpreted Leviticus 16:21 to teach that the goat sent to Azazel could atone for all sins, even sins punishable by death. (Mishnah Shevuot 1:6; Babylonian Talmud Shevuot 2b.)

They would set up guards at stations, and from these would waive towels to signal that the goat had reached the wilderness. When the signal was relayed to Jerusalem, they told the High Priest: “The goat has reached the wilderness.” Rabbi Ishmael taught that they had another sign too: They tied a thread of crimson to the door of the Temple, and when the goat reached the wilderness, the thread would turn white, as it is written in Isaiah 1:18: “Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow.” (Mishnah Yoma 6:8; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 68b.)

Chapter 8 of tractate Yoma in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of self-denial in Leviticus 16:29–34. (Mishnah Yoma 8:1–9; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 73b–88a.) The Mishnah taught that on Yom Kippur, one must not eat, drink, wash, anoint oneself, put on sandals, or have sexual intercourse. Rabbi Eliezer (whom the halachah follows) taught that a king or bride may wash the face, and a woman after childbirth may put on sandals. But the sages forbad doing so. (Mishnah Yoma 8:1; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 73b.) The Mishnah held a person culpable to punishment for eating an amount of food equal to a large date (with its pit included), or for drinking a mouthful of liquid. For the purpose of calculating the amount consumed, one combines all amounts of food together, and all amounts liquids together, but not amounts of foods together with amounts of liquids. (Mishnah Yoma 8:2; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 73b.) The Mishnah obliged one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and drank to bring only one sin-offering. But one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and performed labor had to bring two sin-offerings. The Mishnah did not hold one culpable who ate foods unfit to eat, or drank liquids unfit to drink (like fish-brine). (Mishnah Yoma 8:3; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 81a.) The Mishnah taught that one should not afflict children at all on Yom Kippur. In the two years before they become Bar or Bat Mitzvah, one should train children to become used to religious observances (for example by fasting for several hours). (Mishnah Yoma 8:4; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 82a.) The Mishnah taught that one should give food to a pregnant woman who smelled food and requested it. One should feed to a sick person at the direction of experts, and if no experts are present, one feeds a sick person who requests food. (Mishnah Yoma 8:5; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 82a.) The Mishnah taught that one may even give unclean food to one seized by a ravenous hunger, until the person's eyes are opened. Rabbi Matthia ben Heresh said that one who has a sore throat may drink medicine even on the Sabbath, because it presented the possibility of danger to human life, and every danger to human life suspends the laws of the Sabbath. (Mishnah Yoma 8:6; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 83a.)

Jews Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur (painting by Maurycy Gottlieb)

The Mishnah taught that death and observance of Yom Kippur with penitence atone for sin. Penitence atones for lighter sins, while for severer sins, penitence suspends God's punishment, until Yom Kippur comes to atone. (Mishnah Yoma 8:8; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 85b.) The Mishnah taught that no opportunity for penance will be given to one who says: “I shall sin and repent, sin and repent.” And Yom Kippur does not atone for one who says: “I shall sin and Yom Kippur will atone for me.” Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah derived from the words “From all your sins before the Lord shall you be clean” in Leviticus 16:30 that Yom Kippur atones for sins against God, but Yom Kippur does not atone for transgressions between one person and another, until the one person has pacified the other. Rabbi Akiba said that Israel is fortunate, for just as waters cleanse the unclean, so does God cleanse Israel. (Mishnah Yoma 8:9; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 85b.)

Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said that there never were greater days of joy in Israel than the 15th of Av and Yom Kippur. On those days, the daughters of Jerusalem would come out in borrowed white garments, dance in the vineyards, and exclaim to the young men to lift up their eyes and choose for themselves. (Mishnah Taanit 4:8; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b.)

Leviticus chapter 17[]

The Gemara interpreted the prohibition on consuming blood in Leviticus 17:10 to apply to the blood of any type of animal or fowl, but not to the blood of eggs, grasshoppers, and fish. (Babylonian Talmud Keritot 20b–21a.)

Leviticus chapter 18[]

Applying the prohibition against following the ways of the Canaanites in Leviticus 18:3, the Sages of the Mishnah prohibited going out with talismans like a locust's egg, a fox's tooth, or a nail from a gallows, but Rabbi Meir allowed it, and the Gemara reported that Abaye and Rava agreed, excepting from the prohibition of Leviticus 18:3 any practice of evident therapeutic value. (Mishnah Shabbat 6:10; Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 67a.)

Leviticus 18:4 calls on the Israelites to obey God's “statutes” (hukim) and “ordinances” (mishpatim). The Rabbis in a Baraita taught that the “ordinances” (mishpatim) were commandments that logic would have dictated that we follow even had Scripture not commanded them, like the laws concerning idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery, and blasphemy. And “statutes” (hukim) were commandments that the Adversary challenges us to violate as beyond reason, like those relating to shaatnez (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), halizah (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of the person with tzaraat (in Leviticus 14), and the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16). So that people do not think these “ordinances” (mishpatim) to be empty acts, in Leviticus 18:4, God says, “I am the Lord,” indicating that the Lord made these statutes, and we have no right to question them. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 67b.)

Rabbi Ishmael interpreted the words “he shall live by them” in Leviticus 18:5 to teach that a person should live by the laws, not die by them, and thus one could transgress a commandment to avoid death. And Rabbi Johanan reported in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Jehozadak that a majority in the house of Nithza in Lod voted that a person could transgress any laws to avoid death, except idolatry, incest, or murder. But Rav Dimi taught that one could sin to avoid death only in times when there was no oppressive royal decree against observing the Torah, but in times of such a decree, one needed to suffer martyrdom rather than transgress even a minor precept. And Rabin said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that even absent such a royal decree, sinning to save one's life was permitted only in private; whereas in public, one needed to suffer martyrdom rather than violate even a minor precept. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 74a.)

The Gemara interpreted Leviticus 18:7 to prohibit a man from lying with his father's wife, whether or not she was his mother, and whether or not the father was still alive. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 54a.)

Rav Awira taught (sometimes in the name of Rabbi Ammi, sometimes in the name of Rabbi Assi) that the words “And the child grew, and was weaned (va-yigamal, וַיִּגָּמַל), and Abraham made a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned” in Genesis 21:8 teach that God will make a great feast for the righteous on the day that God manifests (yigmol) God's love to Isaac's descendants. After they have eaten and drunk, they will ask Abraham to recite the Grace after meals (Birkat Hamazon), but Abraham will answer that he cannot say Grace, because he fathered Ishmael. Then they will ask Isaac to say Grace, but Isaac will answer that he cannot say Grace, because he fathered Esau. Then they will ask Jacob, but Jacob will answer that he cannot, because he married two sisters during both their lifetimes, which Leviticus 18:18 was destined to forbid. Then they will ask Moses, but Moses will answer that he cannot, because God did not allow him to enter the Land of Israel either in life or in death. Then they will ask Joshua, but Joshua will answer that he cannot, because he was not privileged to have a son, for 1 Chronicles 7:27 reports, “Nun was his son, Joshua was his son,” without listing further descendants. Then they will ask David, and he will say Grace, and find it fitting for him to do so, because Psalm 116:13 records David saying, “I will lift up the cup of salvation, and call upon the name of the Lord.” (Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 119b.)

A Baraita was taught in the Academy of Eliyahu: A certain scholar diligently studied Bible and Mishnah, and greatly served scholars, but nonetheless died young. His wife carried his tefillin to the synagogues and schoolhouses and asked if Deuteronomy 30:20 says, “for that is your life, and the length of your days,” why her husband nonetheless died young. No one could answer her. On one occasion, Eliyahu asked her how he was to her during her days of white garments — the seven days after her menstrual period — and she reported that they ate, drank, and slept together without clothing. Eliyahu explained that God must have slain him because he did not sufficiently respect the separation that Leviticus 18:19 requires. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 13a–b.)

Mishnah Sanhedrin 7:7 and Babylonian Talmud 64a–b interpreted the laws prohibiting passing one's child through the fire to Molech in Leviticus 18:21, 20:1–5, and Deuteronomy 18:10.

Rabbi Judah ben Pazzi deduced from the juxtaposition of the sexual prohibitions of Leviticus 18 and the exhortation to holiness in Leviticus 19:2 that those who fence themselves against sexual immorality are called holy, and Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that wherever one finds a fence against sexual immorality, one will also find sanctity. (Leviticus Rabbah 24:6.)

Commandments[]

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 2 positive and 26 negative commandments in the parshah:

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple in Jerusalem indiscriminately. (Leviticus 16:2.)

- To follow the procedure of Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16:3.)

- Not to slaughter sacrifices outside the courtyard (Leviticus 17:4.)

- To cover the blood of a slaughtered beast or fowl with earth (Leviticus 17:13.)

- Not to make pleasurable sexual contact with any forbidden woman (Leviticus 18:6.)

- Not to have homosexual sexual relations with one's father (Leviticus 18:7.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's mother (Leviticus 18:7.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's father's wife (Leviticus 18:8.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's sister (Leviticus 18:9.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's son's daughter (Leviticus 18:10.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's daughter's daughter (Leviticus 18:10.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's daughter (Leviticus 18:10.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's father's wife's daughter (Leviticus 18:11.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's father's sister (Leviticus 18:12.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's mother's sister (Leviticus 18:13.)

- Not to have homosexual sexual relations with one's father's brother (Leviticus 18:14.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's father's brother's wife (Leviticus 18:14.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's son's wife (Leviticus 18:15.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's brother's wife (Leviticus 18:16.)

- Not to have sexual relations with a woman and her daughter (Leviticus 18:17.)

- Not to have sexual relations with a woman and her son's daughter (Leviticus 18:17.)

- Not to have sexual relations with a woman and her daughter's daughter (Leviticus 18:17.)

- Not to have sexual relations with one's wife's sister while both are alive (Leviticus 18:18.)

- Not to have sexual relations with a menstrually impure woman (Leviticus 18:19.)

- Not to pass one's children through the fire to Molech (Leviticus 18:21.)

- Not to have male homosexual sexual relations (Leviticus 18:22.)

- A man must not have sexual relations with a beast. (Leviticus 18:23.)

Ezekiel (painting by Michelangelo)

- A woman must not have sexual relations with a beast. (Leviticus 18:23.)

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 2:275–377. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1984. ISBN 0-87306-296-5.)

Haftarah[]

The haftarah for the parshah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 22:1–19

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 22:1–16

Both the parshah (in Leviticus 18) and the haftarah (in Ezekiel 22:10–11) address prohibited sexual practices.

On Shabbat HaGadol[]

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat HaGadol (the special Sabbath immediately before Passover — as it does in 2008, 2011, and 2014), the haftarah is Malachi 3:4–24. Shabbat HaGadol means “the Great Sabbath,” and the haftarah for the special Sabbath refers to a great day that God is preparing. (Mal. 3:17–19)

Amos (illustration by Gustave Doré)

Parshah Acharei-Kedoshim[]

When parshah Acharei is combined with parshah Kedoshim (as it is in 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015), the haftarah is the haftarah for parshah Kedoshim:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Amos 9:7–15

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 20:2–20

The Weekly Maqam[]

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parshah. For parshah Acharei, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Hijaz, the maqam that expresses mourning and sadness. This maqam is appropriate for this parshah because the parshah alludes to the deaths of Nadab and Abihu, the first two sons of Aaron.

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient[]

- “Temple Program for the New Year’s Festival at Babylon.” Babylonia. Reprinted in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Edited by James B. Pritchard. 331–34. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. ISBN 0691035032.

Biblical[]

- Leviticus 14:4–7, 49–53 (riddance ritual); 20:2 (Molech); 23:26–32 (Yom Kippur).

- Deuteronomy 18:10 (passing children through the fire).

- 1 Kings 11:4–8, 33 (Molech).

- 2 Kings 16:3 (son pass through fire); 17:17 (children pass through fire); 21:6 (son pass through fire); 23:10–14 (Molech).

- Isaiah 57:9 (Molech or king).

- Jeremiah 7:31 (child sacrifice); 32:35 (Molech); 49:1–3 (Molech or Malcam).

- Ezekiel 16:20–21 (sacrificing children); 18:5–6 (the just man avoids contact with the menstruating woman); 23:37 (sacrifice of sons).

- Amos 5:25–27 (Molech or king).

- Zephaniah 1:4–6 (Molech).

- Psalms 32:2 (God's imputing iniquity to a person); 51:3–4 (cleansing from sin); 93:5 (holiness in God's house); 103:1–18 (God's forgiveness); 106:37 (sacrifice to demons).

- 2 Chronicles 33:6 (children pass through fire).

Philo

Early nonrabbinic[]

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 2:14:52, 15:56; That the Worse Is Wont To Attack the Better 22:80; On the Posterity of Cain and His Exile 20:70; On the Giants 8:32; Who Is the Heir of Divine Things? 16:84; On Mating with the Preliminary Studies 16:85–87; On Flight and Finding 28:159; 34:193; On Dreams, That They Are God-Sent 2:28:189, 34:231; The Special Laws 4:23:122. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century C.E.. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 43, 121, 138, 154, 283, 311, 335, 338, 401, 404, 628. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:10:3, 11:2, 12:1. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 95. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Acts of the Apostles 7:42–43 (Molech).

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Bikkurim 2:9; Shabbat 6:10; Shekalim 4:2; Yoma 1:1–8:9; Megillah 3:5; 4:9; Chagigah 2:1; Yevamot 2:3; Sotah 7:7; Sanhedrin 7:4; 9:1; Makkot 3:15; Shevuot 1:4–7; Zevachim 12:5; 14:1–2, 9; Menachot 9:7; Keritot 1:1; 2:4; 5:1; Parah 1:4. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 171, 256, 265–79, 321, 323, 330, 339, 459, 597, 602, 619, 621–22, 726, 729, 731, 752, 836, 839, 845–46, 1014. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Sifra 174:1–194:3. Land of Israel, 4th Century C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 3:1–84. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-207-0.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Kilayim 76a; Maaser Sheni 12a; Yoma 1a–; Sukkah 3b, 27a; Beitzah 1a–. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 5, 10, 22. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2008–2009.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 9:5; 37:2; 47:1; 48:2; 54:1; 60:4; 69:3; 74:5. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, 29, 163, 205, 215, 243, 275, 317, 348. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006. ISBN 0-8276-0799-7.

- Leviticus Rabbah 5:6; 17:3; 20:1–23:13; 27:9. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, 4:71, 216, 250–303, 354. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

Talmud

- Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 13a–b, 22a, 67a, 86a; Pesachim 22a, 26a, 47b, 65a, 75b, 77a, 79a, 85b; Yoma 2a–88a; Sukkah 5a, 24a, 28a, 33a; Beitzah 2a, 7a–8a; Rosh Hashanah 26a; Megillah 7b, 20b, 24a, 25a, 30b–31a; Moed Katan 9a, 15b, 28a; Chagigah 9a, 10a, 11b, 16a, 23b; Yevamot 2a, 3a–b, 5b–8b, 11a, 13a, 17b, 19a, 21a–23a, 28b, 33b, 49a, 50a, 54b–55b, 56b, 83b, 97a, 102b, 114a; Ketubot 29a, 30a, 32b–33a, 36a, 47b, 56a, 72a, 82b; Nedarim 51a, 78a; Sotah 4b, 16a, 17a, 26b, 40b–41a; Gittin 54b, 60a; Kiddushin 13b–14a, 22b, 43a, 44b, 50b–51a, 57b, 67b–68a; Bava Kamma 32a, 38a, 40b, 41a, 76a, 91b, 96b; Bava Batra 25a, 88b, 109b, 120a–21a; Sanhedrin 12b, 18a, 19b, 28b, 33b, 34b, 42b, 43b, 49b, 51a, 52b, 53b–55a, 57b, 58b–59a, 60b–61a, 74a, 75b–76a, 81a, 82a; Makkot 5b, 13a–14b, 18a, 23a–24a; Shevuot 2a–b, 7b–8b, 12a–14a, 17b–18b; Avodah Zarah 3a, 11a, 17a–b, 27b, 47a, 51a–b, 54a, 74a; Horayot 6a, 8b, 13a; Zevachim 6a, 19b, 26a–b, 35a, 40a, 46a, 52a, 57a, 69a–70a, 78a, 81a, 83a, 84b, 98a, 104a, 105a–09b, 112a–b, 113b, 116b, 118a, 119b; Menachot 8b, 12b, 16a, 22a, 26a, 27a–b, 83a, 91b–92a, 93b; Chullin 10b–11a, 16b–17a, 20b, 22a, 24a, 27b, 29b, 31a, 41b, 72a, 78a, 79b, 83b–84a, 85a, 86b–87a, 88a, 98b, 117a, 120a, 131b, 138a–39a; Bekhorot 39b, 56b; Temurah 2b, 5b, 6b, 12a, 13a, 14a, 29b; Keritot 2a–3b, 4b, 5a, 6a–b, 9a, 10b, 14a–15a, 20b–21a, 22a, 25b, 28a; Meilah 11a–b, 13b; Niddah 35a, 55a–b. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval[]

- Rashi. Commentary. Leviticus 16–18. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 3:191–223. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-028-5.

Maimonides

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 3:53. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 181. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Intro.:25; Structure. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, 3:37, 41, 46, 47, 48, 49. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, 334, 346, 362–64, 366, 369, 371, 376–77. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Zohar 3:56a–80a. Spain, late 13th Century.

Modern[]

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:40, 41. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 503–04, 513–14. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 79, 82–83, 147–48, 152–53, 189, 201–02, 226–27, 336, 351, 384–86, 927. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- James A. Michener. The Source, 106–20. New York: Random House, 1965.

- Joel Roth. “Homosexuality.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1992. EH 24.1992b. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 613–75. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel, 3–4. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993. ISBN 1-56000-081-3.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Does the Bible Prohibit Homosexuality? The biblical prohibition is addressed only to Israel. It is incorrect to apply it on a universal scale.” Bible Review. 9 (6) (Dec. 1993).

- Jacob Milgrom. “How Not to Read the Bible: I am not for homosexuality, but I am for homosexuals. When the Bible is distorted to make God their enemy I must speak out to set the record straight.” Bible Review. 10 (2) (Apr. 1994).

- Calum M. Carmichael. Law, Legend, and Incest in the Bible: Leviticus 18–20, at 1–61, 189–98. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8014-3388-6.

- Jacob Milgrom. “The Blood Taboo: Blood should not be ingested because it contains life. Whoever does so is guilty of murder.” Bible Review. 13 (4) (Aug. 1997).

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 1–16, 3:1009–84. New York: Anchor Bible, 1998. ISBN 0-385-11434-6.

- Mary Douglas. Leviticus as Literature, 10, 33, 37, 62, 72, 76, 79, 90–92, 123, 131, 137, 140, 151, 187, 191–94, 225–26, 228, 231–40, 247–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-924419-7.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 17–22, 3A:1447–593. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000. ISBN 0-385-41255-X.

- Susan Ackerman. “When the Bible Enters the Fray: As Vermont legalizes civil unions for same-sex couples, both sides of the debate turn to the Bible for support. They might do better to turn to Bible scholars, too.” Bible Review. 16 (5) (Oct. 2000): 6, 50.

- Elliot N. Dorff, Daniel S. Nevins, and Avram I. Reisner. “Homosexuality, Human Dignity & Halakhah: A Combined Responsum for the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2006.

- Joel Roth. “Homosexuality Revisited.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2006.

- Gordon Tucker. “Halakhic and Metahalakhic Arguments Concerning Judaism and Homosexuality.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2006.

- Jennifer K. Berenson MacLean. “Barabbas, the Scapegoat Ritual, and the Development of the Passion Narrative.” Harvard Theological Review 100 (3) (July 2007):309–34.

See also[]

- Azazel in rabbinic literature

- Homosexuality and Conservative Judaism

- Leviticus 18

External links[]

Texts[]

Commentaries[]

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- American Jewish University

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- Orthodox Union

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

| |||||||||||||||||||