Hercules kills the Lernaean Hydra in this 15th century painting by Antonio del Pollailo.

Hercules is the Roman name for Greek demigod Heracles, son of Jupiter (the Roman equivalent of Zeus), and the mortal Alcmene. Early Roman sources suggest that the imported Greek hero supplanted a mythic Italic shepherd called "Recaranus" or "Garanus", famous for his strength who dedicated the Ara Maxima that became associated with the earliest Roman cult of Hercules.[1] While adopting much of the Greek Heracles' iconography and mythology as his own, Hercules adopted a number of myths and characteristics that were distinctly Roman. With the spread of Roman hegemony, Hercules was worshiped locally from Hispania through Gaul.

Etymology[]

Hercules's Latin name was not directly borrowed from Greek Heracles but is a modification of the Etruscan name Herceler, which derives from the Greek name via syncope, Heracles translates to "The Glory of Hera". An oath invoking Hercules (Hercle! or Mehercle!) was a common interjection in Classical Latin.[2]

In art[]

In Roman works of art and in Renaissance and post-Renaissance art that adapts Roman iconography, Hercules can be identified by his attributes, the lion skin and the gnarled club (his favorite weapon): in mosaic he is shown tanned bronze, a virile aspect.[3]

In mythology[]

According to mythology, Hercules was the illegitimate son of Jupiter and Alcmene, the wisest and most beautiful of all mortal women. Juno was enraged at Jupiter for his infidelity with Alcmene, and even more so that he placed the infant Hercules at Juno's breast as she slept and allowed him to feed, which caused Hercules to be partially immortal, thus, allowing him to surpass all mortal men in strength, size and skill.

Juno held a spiteful grudge against Hercules and sent him into a blind frenzy, in which he killed all of his children and his wife. When Hercules regained his sanity, he sought out the Oracle at Delphi in the hope of making atonement. The Oracle ordered Hercules to serve Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, who sent him on a series of tasks known as the Labors of Hercules. These tasks are told in this order:

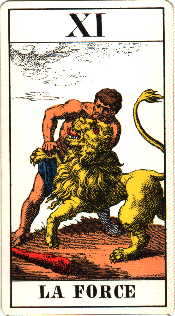

This card from a 19th-century Swiss Tarot deck depicts Hercules fighting the Nemean lion.

- To kill the Nemean lion

- To destroy the Lernaean Hydra

- To capture Ceryneian Hind alive

- To trap the Erymanthian Boar

- To clean the Augean stables

- To get rid of the Stymphalian birds

- To capture the Cretan Bull

- To round up the Mares of Diomedes

- To fetch Hippolyta's girdle, or belt

- To fetch the cattle of Geryon

- To fetch the golden apples of the Hesperides

- To bring Cerberus from Tartarus.

While he was a champion and a great warrior, he was not above cheating and using any unfair trick to his advantage. However, he was renowned as having "made the world safe for mankind" by destroying many dangerous monsters. Although he was a famous demigod, he still could not prevent his death.

Death of Hercules[]

Hercules kills the centaur Nessus. 1899 painting by Franz Stuck.

Hercules was married to Deianira. Long after their marriage, one day the centaur Nessus offered to ferry them across a wide river that they had to cross. Nessus set off with Deianira first, but tried to abduct her. When Hercules realized the centaur's real intention, Hercules chased after him and shot him with an arrow which was poisoned with Hydra's blood. Before he died, Nessus told Deianira to take some of his blood and treasure it, since it was a very powerful medicine and: if she ever thought Hercules was being unfaithful, the centaur told her, the blood would restore his love. Deianira kept the vial of blood.

Many years after that incident she heard rumours that Hercules had fallen in love with another woman. She smeared some of the blood on a robe and sent it to Hercules by a servant named Leechas. When doing so, some of the blood was spilled on the floor and when the sun rays fell on it the blood begun to burn. Because of this Deianeira began to suspect Nessus's advice and decided to send another servant to fetch Leechas back before he could hand over the blood soaked robe to Hercules. She was too late. Hercules had already put on the robe and when he did so the blood still poisoned from the same arrow used by Hercules, burnt into his flesh. When he jumped into a nearby river in hope of extinguishing the fire, it only made it worse. When he tried to rip off the robe from his body his organs were also ripped off with it. Furiously, Hercules caught Leechas and tossed him into the sea. After that he told his friend Philoctetes to build him a pyre on mount Oata. He was burnt to death on the pyre. Before dying, Hercules offered his bow and arrows as a token of gratitude to Philoctetes. His father Jupiter then turned him into a god. Deianeira, after hearing what she had caused, committed suicide.

Germanic association[]

Tacitus records a special affinity of the Germanic peoples for Hercules. In chapter 3 of his Germania, Tacitus states:

... they say that Hercules, too, once visited them; and when going into battle, they sang of him first of all heroes. They have also those songs of theirs, by the recital of this barditus[4] as they call it, they rouse their courage, while from the note they augur the result of the approaching conflict. For, as their line shouts, they inspire or feel alarm.

In the Roman era Hercules' Club amulets appear from the 2nd to 3rd century, distributed over the empire (including Roman Britain, c.f. Cool 1986), mostly made of gold, shaped like wooden apples. A specimen found in Köln-Nippes bears the inscription "DEO HER[culi]", confirming the association with Hercules.

In the 5th to 7th centuries, during the Migration Period, the amulet is theorized to have rapidly spread from the Elbe Germanic area across Europe. These Germanic "Donar's Clubs" were made from deer antler, bone or wood, more rarely also from bronze or precious metals. They are found exclusively in female graves, apparently worn either as a belt pendant, or as an ear pendant. The amulet type is replaced by the Viking Age Thor's hammer pendants in the course of the Christianization of Scandinavia from the 8th to 9th century.

In numismatics[]

Hercules has been the main motif of many collector coins and medals, the most recent one is the 20 euro Baroque Silver coin issued on September 11, 2002. The obverse side of the coin shows the Grand Staircase in the town palace of Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna, currently the Austrian Ministry of Finance. Gods and demigods hold its flights, while Hercules stands at the turn of the stairs.

Hercules filmography[]

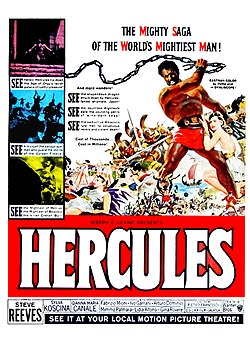

American magazine ad for the 1958 film Hercules.

A series of nineteen Italian Hercules movies were made in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The actors who played Hercules in these films were Steve Reeves, Gordon Scott, Kirk Morris, Mickey Hargitay, Mark Forest, Alan Steel, Dan Vadis, Brad Harris, Reg Park, Peter Lupus (billed as Rock Stevens) and Michael Lane. The films are listed below by their American release titles, and the titles in parentheses are the original Italian titles with English translation.

- Hercules (Le Fatiche di Ercole/ The Labors of Hercules, 1957) starring Steve Reeves

- Hercules Unchained (Ercole e la regina di Lidia/ Hercules and the Queen of Lydia, 1959) starring Steve Reeves

- Goliath and the Dragon (La Vendetta di Ercole/ The Revenge of Hercules, 1960) (this Hercules film had its title changed to Goliath when it was distributed in the U.S.)

- Hercules Vs The Hydra (Gli Amori di Ercole/ The Loves of Hercules, 1960) co-starring Jayne Mansfield

- Hercules and the Captive Women (Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide/Hercules at the Conquest of Atlantis, 1961) (alternate U.S. title: Hercules and the Haunted Women)

- Hercules in the Haunted World (Ercole al centro della terra/Hercules at the Center of the Earth) 1961 (directed by Mario Bava)

- Hercules in the Vale of Woe (Maciste contro Ercole nella valle dei guai/Maciste Vs. Hercules in the Vale of Woe) 1961

- Ulysses Vs. The Son of Hercules (Ulisse contro Ercole/Ulysses Vs. Hercules) 1962

- The Fury of Hercules (La Furia di Ercole/The Fury of Hercules, a.k.a. The Fury of Samson) 1962

- Hercules, Samson and Ulysses (Ercole sfida Sansone/Hercules Challenges Samson) 1963

- Hercules Vs. the Moloch (Ercole contro Molock/Hercules Vs. Moloch, 1963) (alternate U.S. title: The Conquest of Mycene)

- Son of Hercules in the Land of Darkness (Ercole l'invincibile/Hercules, the Invincible) 1964 (this was originally a Hercules film that was retitled to "Son of Hercules" so that it could be included in the "Sons of Hercules" TV syndication package)

- Hercules Vs. The Giant Warrior (il Trionfo di Ercole/The Triumph of Hercules, 1964) (alternate U.S. title: Hercules and the Ten Avengers)

- Hercules Against Rome (Ercole contro Roma, 1964)

- Hercules Against the Sons of the Sun (Ercole contro i figli del sole, 1964)

- Hercules and the Tyrants of Babylon (Ercole contro i tiranni di Babilonia, 1964)

- Samson and the Mighty Challenge (Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili, 1964) (a.k.a. Combate dei Gigantes)

- Hercules and the Princess of Troy (a.k.a. Hercules vs. the Sea Monster) No Italian title, 1965 (this 48-minute Italian/U.S. co-production was made as a pilot for a Charles Band-produced TV series that never materialized)

- Hercules, the Avenger (Sfida dei giganti/Challenge of the Giants, 1965) This film was composed mostly of stock footage from 2 earlier Reg Park Hercules films, made to be released directly to U.S. television

A number of English-dubbed Italian films that featured the Hercules name in their title were never intended to be Hercules movies by their Italian creators.

- Hercules, Prisoner of Evil was actually a retitled Ursus film.

- Hercules and the Black Pirate and Hercules and the Treasure of the Incas were both retitled Samson movies.

- Hercules and the Masked Rider was actually a retitled Goliath movie.

- Hercules Against the Moon Men, Hercules Against the Barbarians, Hercules Against the Mongols and Hercules of the Desert were all originally Maciste films.

None of these films in their original Italian versions were connected to the Hercules character in any way. Likewise, most of the Sons of Hercules movies shown on American TV in the 1960s had nothing to do with Hercules in their original Italian incarnations.

- The Three Stooges made an American comedy in 1962 called The Three Stooges withSamson Burke playing Hercules.

- In 1970 Arnold Schwarzenegger starred in Hercules in New York.

References[]

- Notes

- ↑ Servius, commentary on the Aeneid]] viii. 203, 275 ; Macrobius, Saturnalia iii. 12.

- ↑ W. M. Lindsay, "Mehercle and Herc(v)lvs. [Mehercle and Herc(u)lus]" The Classical Quarterly 12.2 (April 1918:58).

- ↑ Hercules almost suggests "Hero". The Classical and Hellenistic convention in frescoes and mosaics, adopted by the Romans, is to show women as pale-skinned and men as tanned dark from their outdoor arena of action and exercising in the gymnasium.(See also Reed.edu, jpg file. Reed.edu, subject).

- ↑ or, baritus, there being scribal variants. In the 17th century, the word entered the German language as barditus and was associated with the Celtic bards.

- Sources

- Charlotte Coffin. "Hercules" in Peyré, Yves (ed.) A Dictionary of Shakespeare's Classical Mythology (2009)

External links[]

Media related to Hercules on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hercules on Wikimedia Commons- Etruscan mirror illustrated Uni and Hercle

- Hercle and Menerva on an Etruscan mirror from Città di Castello, c 300 B.C.: Badisches Landesmuseum

- Images of Hercules

| |||||

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original article was at Hercules. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |