Chukat, Hukath, or Chukkas (Hebrew: חקת, “decree,” — the ninth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parshah) is the 39th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the sixth in the book of Numbers. It constitutes Numbers 19:1–22:1. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in late June or July.

The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying among years. In most years (for example, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017), parshah Chukat is read separately. In some years (for example, 2009), parshah Chukat is combined with the subsequent parshah, Balak, to help achieve the needed number of weekly readings.

Jews also read the first part of the parshah, Numbers 19:1–22, in addition to the regular weekly Torah portion, on the Sabbath after Purim, called Shabbat Parah. On Shabbat Parah, a reader chants the regular weekly Torah portion first, and then a reader chants the chapter of the red cow (parah adumah). Shabbat Parah occurs shortly before Passover, and Numbers 19:1–22 sets out the procedure by which the Israelites could purify themselves from the contamination caused by a corpse, and so prepare for the pilgrimage festival of Passover.

Moses Striking Water from the Rock (painting by Nicolas Poussin)

Summary[]

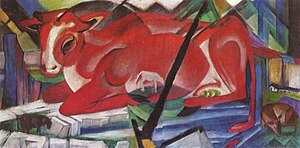

The World Cow (1913 painting by Franz Marc)

The red cow[]

God told Moses and Aaron to instruct the Israelites the ritual law of the red cow (Hebrew "parah aduma") used to create water of lustration. (Numbers 19:1–2.) The cow had to be without blemish, have no defect, and not have borne a yoke. (Numbers 19:2.) Eleazar the priest was to take it outside the camp, observe its slaughter, and take some of its blood with his finger and sprinkle it seven times toward the Tabernacle. (Numbers 19:3–4.) The cow was to be burned in its entirety along with cedar wood, hyssop, and crimson stuff. (Numbers 19:5–6.) The priest and the one whom burned the cow were both to wash their garments, bathe in water, and be unclean until evening. (Numbers 19:7–8.) The ashes of the cow were to be used to create the water of lustration. (Numbers 19:9.)

One who touched the corpse of any human being was to be unclean for seven days. (Numbers 19:10–11.) On the third and seventh days, the person who had touched the corpse was to cleanse with the water of lustration and then be clean. (Numbers 19:12.) One who failed to do so would remain unclean, would defile the Tabernacle, and would be cut off from Israel. (Numbers 19:12–13.)

When a person died in a tent, whoever entered the tent was to be unclean seven days, and every open vessel in the tent was to be unclean. (Numbers 19:14–15.) In the open, anyone who touched a corpse, bone, or a grave was to be unclean seven days. (Numbers 19:16.)

Moses Brings Water Out of the Rock (illustration from the 1728 Figures de la Bible)

A person who was clean was to add fresh water to ashes of the red cow, dip hyssop it in the water, and sprinkle the water on the tent, the vessels, and people who had become unclean. (Numbers 19:17–18.) The person who sprinkled the water was then to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and be clean at nightfall. (Numbers 19:19.)

Anyone who became unclean and failed to cleanse himself was to be cut off from the congregation. (Numbers 19:20.) The person who sprinkled the water of lustration was to wash his clothes, and whoever touched the water of lustration, whatever he touched, and whoever touched him were to be unclean until evening. (Numbers 19:21–22.)

Miriam’s death[]

The Israelites arrived at Kadesh in the wilderness of Zin, and Miriam died and was buried there. (Numbers 20:1.)

Moses Brings Forth Water out of the Rock (fresco by Giotto di Bondone at the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua)

Water from a rock[]

The people were without water, and they complained against Moses and Aaron. (Numbers 20:2–5.) Moses and Aaron fell on their faces at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, and the Presence of God appeared to them, telling them to take the rod and order the rock to yield its water. (Numbers 20:6–8.) Moses took the rod, assembled the congregation in front of the rock, and said to them: “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?” (Numbers 20:9–10.) Then Moses struck the rock twice with his rod, out came water, and the community and their animals drank. (Numbers 20:11.) But God told Moses and Aaron: “Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them.” (Numbers 20:12.)

Embassy to Edom[]

Moses sent messengers to the king of Edom asking him to allow the Israelites to cross Edom, without passing through fields or vineyards, and without drinking water from wells. (Numbers 20:14–17.) But the Edomites would not let the Israelites pass through, and turned out in heavy force to block their way, and the Israelites turned away. (Numbers 20:18–21.)

The Brazen Serpent (painting by James Tissot)

Aaron’s death[]

The Brazen Serpent by Benjamin West

At Mount Hor, God told Moses and Aaron: “Let Aaron be gathered to his kin: he is not to enter the land that I have assigned to the Israelite people, because you disobeyed my command about the waters of Meribah.” (Numbers 20:23–24.) Moses took Aaron and his son Eleazar up on Mount Hor, and there he stripped Aaron of his vestments and put them on Eleazar, and Aaron died there. (Numbers 20:25–28.) The Israelites mourned Aaron 30 days. (Numbers 20:29.)

Victory over Arad[]

The king of Arad engaged the Israelites in battle and took some of them captive. (Numbers 21:1.) The Israelites vowed that if God gave them victory, they would destroy Arad. (Numbers 21:2.) God delivered up the Canaanites, and the Israelites killed them and destroyed their cities, calling the place Hormah. (Numbers 21:3.)

Serpents[]

The people grew restive and spoke against God and Moses, so God let loose serpents that killed many of the Israelites. (Numbers 21:4–6.) The people came to Moses, admitted their sin by speaking against God, and asked Moses to intercede with God to take away the serpents, and Moses did so. (Numbers 21:7.) God told Moses to mount a serpent figure on a standard, saying: “If anyone who is bitten looks at it, he shall recover.” (Numbers 21:8.)

The Conquest of the Amorites (painting by James Tissot)

Destruction of the Army of the Amorites (illustration by Gustave Doré)

Victories over Sihon and Og[]

The Israelites traveled on, and sent messengers to Sihon, king of the Amorites, asking that he allow them to pass through his country, without entering the fields or vineyards, and without drinking water from wells. (Numbers 21:21–22.) But Sihon would not let Israel pass through his territory and engaged the Israelites in battle. (Numbers 21:23.) The Israelites defeated the Amorites and took possession of their land and towns. (Numbers 21:24–25.)

Then the Israelites marched on, and King Og of Bashan engaged them in battle. (Numbers 21:33.) The Israelites defeated his forces and took possession of his country. (Numbers 21:35.) The Israelites then marched to the steppes of Moab, across the Jordan River from Jericho. (Numbers 22:1.)

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Numbers chapter 19[]

Tractate Parah in the Mishnah and Tosefta interpreted the laws of the red cow in Numbers 19:1–22. (Mishnah Parah 1:1–12:11; Tosefta Parah 1:1–12:19.)

Rabbi Tanhum son of Rabbi Hannilai taught that Numbers 19 was one of two sections in the Torah (along with Leviticus 21, on corpse contamination) that Moses gave the Israelites in writing that are both pure, dealing with the law of purity. Rabbi Tanhum taught that they were given on account of the tribe of Levi, of whom it is written (in Malachi 3:3), “he [God’s messenger] shall purify the sons of Levi and purge them.” (Leviticus Rabbah 26:3.)

Rabbi Joshua of Siknin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the Evil Inclination criticizes four laws as without logical basis, and Scripture uses the expression “statute” (chuk) in connection with each: the laws of (1) a brother's wife (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), (2) mingled kinds (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), (3) the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16), and (4) the red cow (in Numbers 19). In connection with the red cow, the Mishnah noted the paradox that the garments of all those who took any part in the preparation of the red cow became defiled, but the cow itself made garments ritually clean. (Mishnah Parah 4:4.) And Numbers 19:1 applies the term “statute” to the red cow. (Numbers Rabbah 19:5.)

Similarly, a midrash taught that an idolater once asked Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai about the red cow, likening its procedures to witchcraft. Rabbi Johanan asked the idolater what he had seen done for a man possessed by a demon of madness. The idolater explained how in such a case, they would bring roots, make them smoke under the madman, sprinkle water on the man, and the demon would flee. Rabbi Johanan told him that the red cow dealt similarly with the spirit of uncleanness, as Zechariah 13:2 says: “And also I will cause the prophets and the unclean spirit to pass out of the land.” Rabbi Johanan told him that when they sprinkled the water of purification on the unclean, the spirit of uncleanness fled. But when the idolater had gone, Rabbi Johanan's disciples told Rabbi Johanan that they saw that he had put off the idolater with a mere makeshift, and asked him what explanation Rabbi Johanan would give them. Rabbi Johanan told his disciples that the dead did not defile nor the water purify; God had merely laid down a statute, issued a decree, and commanded that we not transgress the decree, as Numbers 19:2 says: “This is the statute of the law.” (Numbers Rabbah 19:8.)

Expounding upon the commandment of the red cow in Numbers 19:2, Rabbi Jose ben Hanina taught that God told Moses the reason for the commandment, but to everyone else it would remain merely a statute. (Numbers Rabbah 19:6.)

All other communal sacrifices were of male animals, but the red cow was of a female animal. Rabbi Aibu explained the difference with a parable: When a handmaiden's boy polluted a king's palace, the king called on the boy's mother to clear away the filth. In the same way, God called on the red cow to come and atone for the incident of the golden calf. (Numbers Rabbah 19:8.)

Rabbi Eliezer ruled that a red cow that was pregnant was nonetheless valid, but the Sages ruled it invalid. Rabbi Eliezer ruled that the red cow could not be purchased from Gentiles, but the Sages ruled that such cow could be valid. (Mishnah Parah 2:1.) If the horns or the hoofs of the red cow were black, they were chopped off, and the red cow was then valid. The cow's eye, teeth, and tongue could cause no invalidity. And a dwarf-like cow was nonetheless valid. If the red cow had a sebaceous cyst and they cut it off, Rabbi Judah ruled the cow invalid, but Rabbi Simeon ruled it invalid only if no red hair grew in its place. (Mishnah Parah 2:2.) A red cow born by a caesarean section, the hire of a harlot, or the price of a dog was invalid. Rabbi Eliezer ruled it valid, for Deuteronomy 23:19 states, “You shall not bring the hire of a harlot or the price of a dog into the house of the Lord your God,” and the red cow was not brought into the Temple. The Mishnah taught that all blemishes that caused consecrated animals to be invalid as sacrifices also caused the red cow to be invalid. If one had ridden on the cow, leaned on it, hung on its tail, crossed a river with its help, doubled up its leading rope, or put one's cloak on it, the cow was invalid. But if one had only fastened it by its leading rope or made for it a sandal to prevent it from slipping, or spread one's cloak on it because of flies, it remained valid. The general rule was that wherever one did something for its own sake, the cow remained valid; but if one did something for the sake of another purpose, it invalidated the cow. (Mishnah Parah 2:3.) If a bird rested on the cow, it remained valid. If a bull mounted it, it became invalid; but Rabbi Judah ruled that if people brought the bull to mate with the cow, the cow became invalid, but if the bull did so on its own, the cow remained valid. (Mishnah Parah 2:4.) If a cow had two black or white hairs growing within one follicle, it was invalid. Rabbi Judah said even within one hollow. If the hairs grew within two adjacent follicles, the cow was invalid. Rabbi Akiba ruled that even if there were four or even five non-red hairs, if they were dispersed, they could be plucked out. Rabbi Eliezer ruled that even as many as 50 such hairs could be plucked. But Rabbi Joshua ben Bathyra ruled that even if it had only one non-red hair on its head and one on its tail, it was invalid. If the cow had two hairs in one follicle with their roots black and their tips red or with their roots red and their tips black, Rabbi Meir taught that what was visible determined validity; but the Sages ruled that validity followed the root. (Mishnah Parah 2:5.)

hyssop

Rab Judah reported in Samuel's name an account of the rarity of completely red cows: When they asked Rabbi Eliezer how far the honor of parents extended, he told of a heathen from Ashkelon named Dama son of Nethinah. The Sages offered Dama a profit of 600,000 gold denarii (or Rab Kahana said 800,000 denarii) in exchange for jewels that he had that the Sages could use in the ephod, but as the key to the jewels lay under Dama's father's pillow, Dama declined the offer so as not to trouble his father. The next year, God rewarded Dama by causing a red heifer to be born in his herd. When the Sages went to buy it, Dama told them that he knew that he could ask for all the money in the world and they would pay it, but he asked for only the money that he had lost in honoring his father. (Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 31a.)

A midrash noted that God commanded the Israelites to perform certain precepts with similar material from trees: God commanded that the Israelites throw cedar wood and hyssop into the Red Heifer mixture of Numbers 19:6 and use hyssop to sprinkle the resulting waters of lustration in Numbers 19:18; God commanded that the Israelites use cedar wood and hyssop to purify those stricken with skin disease in Leviticus 14:4–6; and in Egypt God commanded the Israelites to use the bunch of hyssop to strike the lintel and the two side-posts with blood in Exodus 12:22. (Exodus Rabbah 17:1.)

Rabbi Isaac noted two red threads, one in connection with the red cow in Numbers 19:6, and the other in connection with the scapegoat in the Yom Kippur service of Leviticus 16:7–10 (which Mishnah Yoma 4:2 indicates was marked with a red thread). Rabbi Isaac had heard that one required a definite size, while the other did not, but he did not know which was which. Rav Joseph reasoned that because (as Mishnah Yoma 6:6 explains) the red thread of the scapegoat was divided, that thread required a definite size, whereas that of the red cow, which did not need to be divided, did not require a definite size. Rami bar Hama objected that the thread of the red cow required a certain weight (to be cast into the flames, as described in Numbers 19:6). Raba said that the matter of this weight was disputed by Tannaim (as explained below). Abaye objected (based on Mishnah Parah 3:11) that they wrapped the red thread together with the cedar wood and hyssop. Rabbi Hanin said in the name of Rab that if the cedar wood and the red thread were merely caught by the flame, they were used validly. They objected to Rabbi Hanin based on a Baraita which taught that if the thread caught fire in midair, they brought another thread to prepare the water of lustration. Abaye reconciled the two opinions by interpreting the Baraita to speak of a flame that blazed high above the cow, and interpreting Rabbi Hanin to speak of a subdued flame that consumed the thread near the burning cow. Raba explained the dispute among Tannaim about the weight of the red thread in connection with the red cow. Rabbi taught that they wrapped the cedar wood and hyssop together with the red thread so that they formed one bunch. Rabbi Eleazar the son of Rabbi Simeon said that they wrapped them together so that they had sufficient weight to fall into the midst of the burning cow. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b.)

When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel, he said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that there were three red threads: one in connection with the red cow, the second in connection with the scapegoat, and the third in connection with the person with skin disease (the m’tzora) in Leviticus 14:4. Rav Dimi reported that one weighed ten zuz, another weighed two selas, and the third weighed a shekel, but he could not say which was which. When Rabin came, he said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the thread in connection with the red cow weighed ten zuz, that of the scapegoat weighed two selas, and that of the person with skin disease weighed a shekel. Rabbi Johanan said that Rabbi Simeon ben Halafta and the Sages disagreed about the thread of the red cow, one saying that it weighed ten shekels, the other that it weighed one shekel. Rabbi Jeremiah of Difti said to Rabina that they disagreed not about the thread of the red cow, but about that of the scapegoat. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41b–42a.)

The Mishnah taught that seven days before the burning of the red cow, they removed the priest who was to burn the cow from his house to a room called the stone chamber facing the north-eastern corner of the Temple. The Mishnah taught that throughout the seven days, they sprinkled on the priest a mixture of all the sin-offerings that were there, but Rabbi Jose taught that they sprinkled only on the third and the seventh days. And Rabbi Hanina the deputy high priest taught that on the priest who was to burn the cow they sprinkled all the seven days, but on the one who was to perform the service on Yom Kippur they sprinkled only on the third and the seventh days. (Mishnah Parah 3:1.) To protect against defilement from contact with the dead, they built courtyards over bedrock, and left beneath them a hollow to serve as protection against a grave in the depths. They used to bring pregnant women there to give birth and rear their children in this ritually pure place. They placed doors on the backs of oxen and placed the children upon them with stone cups in their hands. When the children reached the pool of Siloam, the children stepped down, filled the cups with water, and then climbed back up on the doors. Rabbi Jose said that each child used to let down his cup and fill it from on top of the oxen. (Mishnah Parah 3:2.) When the children arrived at the Temple Mount with the water, they got down. Beneath the Temple Mount and the Temple courtyards was a hollow, which protected against contamination from a grave in the depths. At the entrance of the court of the women, they kept a jar of the ashes of the sin-offerings. (Mishnah Parah 3:3.) If they did not find the residue of the ashes of seven red cows, they performed the sprinkling with those of six, of five, of four, of three, of two or of one. (Mishnah Parah 3:5.)

Rabbi Meir taught that Moses prepared the first red cow ashes, Ezra prepared the second, and five were prepared since then. But the Sages taught that seven were prepared since Ezra. They said that Simeon the Just and Johanan the High Priest prepared two each, and Eliehoenai the son of Hakof, Hanamel the Egyptian, and Ishmael the son of Piabi each prepared one. (Mishnah Parah 3:5.)

The Mishnah taught that they bound the red cow with a bast rope and placed it on the pile with its head towards the south and its face towards the west. The priest stood on the east side facing west. He slaughtered the cow with his right hand and received the blood with his left hand. But Rabbi Judah said that he received the blood with his right hand, put it on his left hand, and then sprinkled with his right hand. He dipped his finger in the blood and sprinkled it towards the Holy of Holies seven times, dipping once for each sprinkling. When he had finished the sprinkling, he wiped his hand on the body of the cow, climbed down, and kindled the fire with wood chips. But Rabbi Akiba said that he kindled the fire with dry branches of palm trees. (Mishnah Parah 3:9.) When the cow's carcass burst in the fire, the priest took up a position outside the pit, took hold of the cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool, and said to the observers: “Is this cedar wood? Is this hyssop? Is this scarlet wool?” He repeated each question three times, and the observers answered “Yes” three times to each question. (Mishnah Parah 3:10.) The priest then wrapped the cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool together with the ends of the wool and cast them into the burning pyre. When the fire burned out, they beat the ashes with rods and then sifted them with sieves. They then divided the ashes into three parts: One part was deposited on the rampart, one on the Mount of Olives, and one was divided among the courses of priests who performed the Temple services in turn. (Mishnah Parah 3:11.)

Rabbi Akiba interpreted the words “and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean” in Numbers 19:19 to teach that if the sprinkler sprinkled upon an unclean person, the person became clean, but if he sprinkled upon a clean person, the person became unclean. The Gemara explained that Rabbi Akiba's view hinged on the superfluous words “upon the unclean,” which must have been put in Numbers 19:19 to teach this. But the Sages held that these effects of sprinkling applied only in the case of things that were susceptible to uncleanness. The Gemara explained that the Rabbis’ view could be deduced from the logical proposition that the greater includes the lesser: If sprinkling upon the unclean makes clean, how much more so should sprinkling upon the clean keep clean or make cleaner? And the Gemara said that it is with reference to Rabbi Akiba's position that Solomon said in Ecclesiastes 7:23: “I said, ‘I will get wisdom,’ but it is far from me.” That is, even Solomon could not explain it. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 14a.)

Numbers chapter 20[]

Rabbi Jose the son of Rabbi Judah taught that three good leaders arose for Israel — Moses, Aaron, and Miriam — and for their sake Providence conferred three good things on Israel — the well that accompanied the Israelites on their journeys for the merit of Miriam, the pillar of cloud for the merit of Aaron, and the manna for the merit of Moses. When Miriam died, the well disappeared, as Numbers 20:1 reports, “And Miriam died there,” and immediately thereafter Numbers 20:2 reports, “And there was no water for the congregation.” The well returned for the merit of Moses and Aaron. When Moses died, the well, the pillar of cloud, and the manna all disappeared, as Zechariah 11:8 reports, “And I cut off the three shepherds in one month.” (Babylonian Talmud Taanit 9a.)

Moses Striking the Rock in Horeb (engraving by Gustave Doré from the 1865 La Sainte Bible)

The Mishnah counted the well that accompanied the Israelites through the desert in the merit of Miriam, or others say, the well that Moses opened by striking the rock in Numbers 20:11, among ten miraculous things that God created at twilight on the eve of the first Sabbath. (Mishnah Avot 5:6.)

A midrash interpreted Numbers 20:11 to teach that Moses struck the rock once and small quantities of water began to trickle from the rock, as Psalm 78:20 says, “Behold, He smote the rock, that waters issued.” Then the people ridiculed Moses, asking if this was water for sucklings, or babes weaned from milk. So Moses lost his temper and struck the rock “twice; and water came forth abundantly” (in the words of Numbers 20:11), overwhelming all those who had railed at Moses, and as Psalm 78:20 says, “And streams overflowed.” (Numbers Rabbah 19:9.)

Reading God's criticism of Moses in Numbers 20:12, “Because you did not believe in Me,” a midrash asked whether Moses had not previously said worse when in Numbers 11:22, he showed a greater lack of faith and questioned God's powers asking: “If flocks and herds be slain for them, will they suffice them? Or if all the fish of the sea be gathered together for them, will they suffice them?” The midrash explained by relating the case of a king who had a friend who displayed arrogance towards the king privately, using harsh words. The king did not, however, lose his temper with his friend. Later, the friend displayed his arrogance in the presence of the king's legions, and the king sentenced his friend to death. So also God told Moses that the first offense that Moses committed (in Numbers 11:22) was a private matter between Moses and God. But now that Moses had committed a second offense against God in public, it was impossible for God to overlook it, and God had to react, as Numbers 20:12 reports, “To sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel.” (Numbers Rabbah 19:10.)

Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar taught that Moses and Aaron died because of their sin, as Numbers 20:12 reports God told them, “Because you did not believe in Me . . . you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them.” Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar thus taught that had they believed in God, their time would not yet have come to depart from the world. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 55b.)

The Gemara implied that the sin of Moses in striking the rock at Meribah compared favorably to the sin of David. The Gemara reported that Moses and David were two good leaders of Israel. Moses begged God that his sin be recorded, as it is in Numbers 20:12, 20:23–24, and 27:13–14, and Deuteronomy 32:51. David, however, begged that his sin be blotted out, as Psalm 32:1 says, “Happy is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is pardoned.” The Gemara compared the cases of Moses and David to the cases of two women whom the court sentenced to be lashed. One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of Leviticus 25:6. The woman who had eaten unripe figs begged the court to make known for what offense she was being flogged, lest people say that she was being punished for the same sin as the other woman. The court thus made known her sin, and the Torah repeatedly records the sin of Moses. (Babylonian Talmud Yoma 86b.)

Resh Lakish taught that Providence punishes bodily those who unjustifiably suspect the innocent. In Exodus 4:1, Moses said that the Israelites “will not believe me,” but God knew that the Israelites would believe. God thus told Moses that the Israelites were believers and descendants of believers, while Moses would ultimately disbelieve. The Gemara explained that Exodus 4:13 reports that “the people believed” and Genesis 15:6 reports that the Israelites’ ancestor Abraham “believed in the Lord,” while Numbers 20:12 reports that Moses “did not believe.” Thus, Moses was smitten when in Exodus 4:6 God turned his hand white as snow. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 97a.)

The Brazen Serpent (illustration from a Bible card published 1907 by Providence Lithograph Company)

A midrash employed a parable to explain why God held Aaron as well as Moses responsible when Moses struck the rock, as Numbers 20:12 reports, “and the Lord said to Moses and Aaron: ‘Because you did not believe in Me.’” The midrash told how a creditor came to take away a debtor's granary and took both the debtor's granary and the debtor's neighbor’s granary. The debtor asked the creditor what his neighbor had done to warrant such treatment. Similarly, Moses asked God what Aaron had done to be blamed when Moses lost his temper. The midrash taught that it on this account that Deuteronomy 33:8 praises Aaron, saying, “And of Levi he said: ‘Your Thummim and your Urim be with your holy one, whom you proved at Massah, with whom you strove at the waters of Meribah.’” (Numbers Rabbah 19:9.)

Numbers chapter 21[]

The Gemara deduduced that what the King of Arad heard in Numbers 21:1 was that Aaron had died and that the clouds of glory had dispersed, as the previous verse, Numbers 20:29, reports that “all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead.” The King thus concluded that he had received permission to fight the Israelites. (Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 3a.)

The Mishnah taught that the brass serpent of Numbers 21:8–9 effected its miraculous cure because when the Israelites directed their thoughts upward and turned their hearts to God they were healed, but otherwise they perished. (Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 3:8; Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 29a.)

Commandments[]

According to Maimonides[]

Maimonides cited a verse in the parshah for 1 positive commandment:

Moses Maimonides

- To prepare a red heifer so that its ashes are ready (Numbers 19:9.)

(Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandment 113. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 1:125. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4.)

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch[]

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 3 positive commandments in the parshah:

- The precept of the red heifer (Numbers 19:2.)

- The precept of the ritual uncleanness of the dead (Numbers 19:14.)

- The precept of the lustral water, that it defiles a ritually clean person and purifies only one defined by the dead (Numbers 19:19.)

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:159–71. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.)

Jephtha's Daughter (1865 engraving by Gustave Doré)

Haftarah[]

The Return of Jephtha (painting by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini)

Generally[]

The haftarah for the parshah is Judges 11:1–33. Both the parshah and the haftarah involve diplomatic missions about land issues. In the parshah, Moses sent messengers and tried to negotiate passage over the lands of the Edomites and the Amorites of Sihon. (Numbers 20:14–21; 21:21–22.) In the haftarah, Jephthah sent messengers to the Ammonites prior to hostilities over their land. (Judges 11:12–27.) In the course of Jephthah's message to the Ammonites, he recounted the embassies described in the parshah. (Judges 11:17–20; Numbers 20:14–17; 21:21–22.) And Jephthah's also recounted the Israelites' victory over the Amorites described in the parshah. (Judges 11:20–22; Numbers 21:23–31.) Both the parshah and the haftarah involve vows. In the parshah, the Israelites vowed that if God delivered the Canaanites of Arad into their hands, then the Israelites would utterly destroy their cities. (Numbers 21:1–2.) In the haftarah, Jephthah vowed that if God would deliver the Ammonites into his hand, then Jephthah would offer as a burnt-offering whatever first came forth out of his house to meet him when he returned. (Judges 11:30–31.) The haftarah concludes just before the verses that report that Jephthah's daughter was first to greet him, proving his vow to have been improvident. (Judges 11:34–35.)

For parshah Chukat–Balak[]

When parshah Chukat is combined with parshah Balak (as it is in 2009), the haftarah is the haftarah for Balak, Micah 5:6–6:8.

For Shabbat Rosh Chodesh[]

When parshah Chukat coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (as it does in 2011 and 2014), the haftarah is Isaiah 66:1–24.

In the liturgy[]

The people's murmuring and perhaps the rock that yielded water at Meribah of Numbers 20:3–13 are reflected in Psalm 95, which is in turn the first of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service. (Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 15. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.)

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient[]

- Ritual To Be Followed by the Kalu-Priest when Covering the Temple Kettle-Drum. Reprinted in James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 334-38. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-691-03503-2.

Biblical[]

- Exodus 17:2–6.

- Leviticus 14:4–6, 49–52 (cedar wood, hyssop, and red stuff).

- Deuteronomy 2:4–8, 2:24–3:11; 10:6.

- 2 Kings 18:4 (bronze serpent).

- Psalm 51:9 (purge with hyssop); 78:15–16, 20, 35 (water from rock; they remembered that God was their Rock); 95:8–11 (Meribah); 105:2 (songs to God); 106:32–33 (Meribah); 135:10–12 (Sihon); 136:17–22 (Sihon).

Josephus

Early nonrabbinic[]

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:4:5–7, 5:1–3. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 107–08. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Hebrews 9:13–14 (red cow); 9:19 (scarlet wool and hyssop). Late 1st Century.

- John 3:14–15 (serpent); 19:29 (hyssop).

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Shekalim 4:2; Rosh Hashanah 3:8; Megillah 3:4; Avot 5:6; Zevachim 14:1; Keritot 1:1; Parah 1:1–12:11. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 256, 304, 321, 686, 729, 836, 1012–35. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Sheviit 47a. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 6b. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006–2009.

Talmud

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 19b, 23a, 28a, 54a, 58a, 63b; Shabbat 16b, 28a, 48b, 51b–52a, 55b, 58b, 60b, 64a, 83b, 84b, 95b, 97a, 101b, 108a, 109a, 137a; Eruvin 54a, 58a, 64b, 67b; Pesachim 14b, 17b, 26b, 34b, 54a, 56a, 65b, 67a, 68a, 70a, 78a, 79a, 92a; Yoma 2a, 4a, 6a, 8a–9a, 14a, 41b–43b, 52b, 68a, 75b, 86b; Sukkah 6a, 21a, 25b, 37a–b; Beitzah 32a; Rosh Hashanah 3a, 29a, 31a; Taanit 9a, 13a; Megillah 6b, 20a, 29a; Moed Katan 5a–b, 7b, 14a, 15b, 28a–b; Chagigah 3b, 4b, 11a, 22a–23a; Yevamot 61a, 71b, 72b–73a, 74a, 75a, 116b; Ketubot 106a; Nedarim 37a, 55a; Nazir 6b, 19a, 44b–45a, 49b, 53b–54a, 61b, 64a; Sotah 12b, 16b, 38b, 46a; Gittin 38a, 53a, 57b, 76a, 86b; Kiddushin 25a, 30b–31a, 36b, 58a–b, 62a; Bava Kamma 2b, 25b, 82b, 98a, 101b, 105a; Bava Metzia 10b, 56b, 58a, 78b, 93a, 114b; Bava Batra 17a; Sanhedrin 4a, 5b, 43b, 47b, 77b, 101b, 110a; Makkot 8a, 11a, 13a, 14b, 21b; Shevuot 6b, 7b, 11b, 16b, 19a; Avodah Zarah 5b, 23a–b, 29b, 32b, 37b, 44a, 46b; Horayot 9b; Zevachim 14b, 17b, 22b, 25b, 32b, 33b, 40a, 43b, 68b, 78b, 80a, 93a–b, 105b, 112a, 113a, 118a; Menachot 6b, 7b, 19a, 27a–b, 51b, 76b; Chullin 2b, 9b, 11a, 13b, 23b–24a, 25a, 29b, 32a, 60b, 62b, 71a–72a, 81b–82a, 88b, 92a, 121a, 124b; Bekhorot 45a, 55a; Arakhin 3a; Temurah 12b; Keritot 2a, 25a; Niddah 5b, 9a, 44a, 49a, 55a, 61a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Rashi

Medieval[]

- Avot of Rabbi Natan, 12:1; 29:7; 34:6; 36:4. Circa 700–900 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan. Translated by Judah Goldin, 64, 120, 139, 150. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1955. ISBN 0-300-00497-4. The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan: An Analytical Translation and Explanation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 89, 179, 205, 217. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986. ISBN 1-55540-073-6.

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 19–22. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 4:225–68. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-029-3.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 3:53. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 181. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

Hobbes

- Numbers Rabbah 19:1–33. 12th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Ecclesiastes Rabbah 7:23

- Zohar 3:179a–184b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern[]

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:33; 4:45. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 417, 675–76. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

Hirsch

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, 514, 574, 582. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 ISBN 0-900689-40-4. Originally published as Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel’s Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. Germany, 1837.

- Emily Dickinson. Poem 168 (If the foolish, call them "flowers" —). Circa 1860. Poem 597 (It always felt to me — a wrong). Circa 1862. In The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, 79–80, 293–94. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-18414-4.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Magic, Monotheism, and the Sin of Moses.” In The Quest for the Kingdom of God: Studies in Honor of George E. Mendenhall. Edited by H. B. Huffmon, F.A. Spina, A.R.W. Green, 251–265. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1983. ISBN 0931464153.

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, 157–84, 438–67. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. ISBN 0-8276-0329-0.

Dickinson

- Mary Douglas. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers, xix, xxvi, 87, 100, 110, 112, 120–21, 123, 126, 130, 140–41, 147, 150, 159, 164, 166–67, 170, 188, 190–92, 199, 207–08, 211, 213, 215–16, 221, 226. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004. ISBN 0-19-924541-X.

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 1–20, 4:455–95. New York: Anchor Bible, 1993. ISBN 0-385-15651-0.

- William H.C. Propp. “Why Moses Could Not Enter The Promised Land.” Bible Review. 14 (3) (June 1998).

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 21–36, 4A:77–133. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000. ISBN 0-385-41256-8.

- Hershel Shanks. “The Mystery of the Nechushtan: Why Did King Hezekiah of Judah Destroy the Bronze Serpent that Moses Had Fashioned To Protect the Israelites.” Biblical Archaeology Review, 33 (2) (Mar./Apr. 2007): 58–63.

- Sara Paretsky. Bleeding Kansas. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2008. ISBN 978-0-399-15405-8. (red heifer plot element).

External links[]

| |||||||||||||||||||