| Thubten Gyatso | |

|---|---|

| 13th Dalai Lama | |

| |

| Reign | 1879–1933 |

| Predecessor | Trinley Gyatso |

| Successor | Tenzin Gyatso |

| Tibetan | ཐུབ་བསྟན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ |

| Wylie | thub bstan rgya mtsho |

| Pronounciation | tʰuptɛ̃ catsʰɔ (IPA) |

| Transcription (PRC) |

Tubdain Gyaco |

| THDL | Thubten Gyatso |

| Chinese | 土登嘉措 |

| Pinyin | Tudeng Jiācuò |

| Born | 12 February 1876 Thakpo Langdun, Ü-Tsang, Tibet |

| Died | 17 December 1933 (aged 57) Lhasa, Tibet |

|

Part of a series on Tibetan Buddhism | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Timeline · Related-topics | |

| Schools | |

| Nyingma · Kagyu · Sakya · Gelug · Bön | |

| Key Concepts | |

| Three marks of existence · Skandha · Cosmology · Saṃsāra · Rebirth · Bodhisattva · Dharma · Dependent Origination · Karma | |

| Major Figures | |

| Gautama Buddha · Padmasambhava · Je Tsongkhapa · Dalai Lama · Panchen Lama · Lama · Karmapa Lama · Rinpoche · Geshe · Terton · Tulku | |

| Buddhahood · Avalokiteśvara · Four Stages of Enlightenment · Tantric yoga · Paramitas · Meditation · Laity | |

|

Major Monasteries | |

| Changzhug · Drepung · Dzogchen · Ganden · Jokhang · Kumbum · Labrang · Mindroling · Namgyal · Narthang · Nechung · Pabonka · Palcho · Ralung · Ramoche · Sakya · Sanga · Sera · Shalu · Tashilhunpo · Tsurphu · Yerpa | |

| Chotrul Duchen · Dajyur · Losar · Monlam · Sho Dun | |

| Texts | |

| Kangyur · Tengyur · Tibetan Canon · Mahayana Sutras | |

|

Art | |

| Sand mandala · Thangka · Ashtamangala · Tree of physiology | |

|

Outline · Comparative Studies · Culture · List of topics · Portal | |

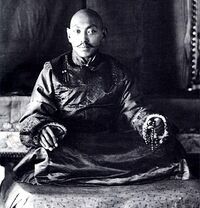

Thubten Gyatso (12 February 1876 – 17 December 1933) was the 13th Dalai Lama of Tibet.[1]

During 1878 he was recognized as the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. He was escorted to Lhasa and given his pre-novice vows by the Panchen Lama, Tenpai Wangchuk, and named "Ngawang Lobsang Thupten Gyatso Jigdral Chokley Namgyal". During 1879 he was enthroned at the Potala Palace, but did not assume political power until 1895,[2] after he had reached his majority.

Thubten Gyatso was an intelligent reformer who proved himself a skilful politician when Tibet became a pawn in The Great Game between Russian Empire, China, and the British Empire. He was responsible for countering the British expedition to Tibet, restoring discipline in monastic life, and increasing the number of lay officials to avoid excessive power being placed in the hands of the monks.

Family[]

The Dalai Lama was born near Sam-ye Monastery, Tak-po province, in 1878.[3]

Agvan Dorzhiev[]

Retreat of the 13th Dalai Lama, Nechung, Tibet

Agvan Dorzhiev, (1854–1938), a Khory Buryat Mongolian, and a Russian subject, was born in the village of Khara-Shibir, not far from Ulan Ude, to the east of Lake Baikal.[4] He left home during 1873 at nineteen to study at the Gelugpa monastery, Drepung, near Lhasa, the largest monastery in Tibet. Having successfully completed the traditional course of religious studies, he began the academic Buddhist degree of Geshey Lharampa (the highest level of 'Doctorate of Buddhist Philosophy').[5] He continued his studies to become Tsanid-Hambo, or "Master of Buddhist Philosophy".[6] He became a tutor and "debating partner" of the teenage Dalai Lama, who became very friendly with him and later used him as an envoy to Russia and other countries.[7]

C.G.E. Mannerheim met Thubten Gyatso in Utaishan during the course of his expedition from Turkestan to Peking. Mannerheim wrote his diary and notes in Swedish (his mother tongue) to conceal the fact that his ethnographic and scientific party was also an ellaborate intelligence gathering mission for the Russian army. The 13th Dalai Lama gave a blessing of white silk for the Russian Tsar and in return received Mannerheim's precious seven-shot officer's pistol with a full explanation of its use as a gift.[8]

- "Obviously," the [Fourteenth] Dalai Lama said, "The Thirteenth Dalai Lama had a keen desire to establish relations with Russia, and I also think he was a little sceptical toward England at first. Then there was Dorjiev. To the English he was a spy, but in reality he was a good scholar and a sincere Buddhist monk who had great devotion to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama."[9]

Military expeditions of Tibet by Britain (1904) and Qing (1910)[]

After the British expedition of Tibet by Sir Francis Younghusband in early 1904, Dorzhiev convinced the Dalai Lama to flee to Urga in Mongolia, almost 2,400 km (1500 miles) to the northeast of Lhasa, a journey which took four months. The Dalai Lama spent over a year in Urga giving teachings to the Mongolians.

After the Dalai Lama fled, the Qing dynasty immediately proclaimed him deposed and again asserted sovereignty over Tibet and made claims over Nepal and Bhutan as well.[10] A peace treaty was signed at the Potala between Britain, the Qing Amban, Nepalese and Bhutanese representatives and the Tibetan government on 7 September 1904. The provisions of the 1904 treaty were confirmed in a 1906 treaty[11] signed between Britain and China. The British, for a fee from the Qing court, also agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet", while China engaged "not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet".[11][12]

During October 1906, John Weston Brooke was the first Englishman to gain an audience with the Dalai Lama, and subsequently he was granted permission to lead two expeditions into Tibet.[13] Also in 1906, Sir Charles Alfred Bell, was invited to visit Thubten Chökyi Nyima, the 9th Panchen Lama at Tashilhunpo, where they had friendly discussions on the political situation.[14]

The Dalai Lama later stayed at the great Kumbum Monastery near Xining and then travelled on to Beijing, where he was granted an audience with Emperor Guangxu and Empress Dowager Cixi. The emperor tried to stress Tibet's subservient role, although the Dalai Lama refused to kowtow to him. He stayed in Beijing until the end of 1908.[10]

When he returned to Tibet during December 1908, he began reorganising the government, but the Qing sent a military expedition of its own to Tibet during 1910 and he had to flee to India.[15][16]

During 1911 the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution and by the end of 1912 the last Qing troops were escorted out of Tibet.

Assumption of political power and independence of Tibet[]

During 1895, Thubten Gyatso assumed ruling power from the monasteries which had previously wielded great influence through the Regent. Due to his two periods of exile in 1904–1909, to escape the British invasion of 1904, and from 1910–1913 to escape a Chinese invasion, he became well aware of the complexities of international politics and was the first Dalai Lama to become aware of the importance of foreign relations. The Dalai Lama, "accompanied by six ministers and a small escort" which included his close aide, diplomat and military figure Tsarong Dzasa, fled via Sikkim to Darjeeling, where they stayed almost two years. During this period he was invited to Calcutta by the Viceroy, Lord Minto, which helped restore relations with the British.[17]

Thubten Gyatso returned to Tibet during January 1913 with Tsarong Dzasa from Darjeeling, where he had been living in exile. The new Chinese government apologised for the actions of the previous Qing dynasty and offered to restore the Dalai Lama to his former position. He replied that he was not interested in Chinese ranks and was assuming spiritual and political leadership of Tibet.[18]

After his return from exile in India during 1913, Thubten Gyatso assumed control of foreign relations and dealt directly with the Maharaja and the British Political officer in Sikkim and the king of Nepal rather than letting the Kashag or parliament do it.[19]

Thubten Gyatso declared independence from China during early 1913, after returning from India following three years of exile. He then standardized the Tibetan flag in its present form.[20] At the end of 1912 the first postage stamps of Tibet were edited.

Thubten Gyatso built a new medical college (Mentsikang) during 1913 on the site of the post-revolutionary traditional hospital near the Jokhang.[21]

Legislation was introduced to counter corruption among officials, a national taxation system was established and enforced, and a police force was created. The penal system was revised and made uniform throughout the country. "Capital punishment was completely abolished and corporal punishment was reduced. Living conditions in jails were also improved, and officials were designated to see that these conditions and rules were maintained."[22][23]

A secular education system was introduced in addition to the religious education system. Thubten Gyatso sent promising students to foreign lands to study, and welcomed foreigners, including Japanese, British and Americans.[22]

As a result of his travels and contacts with foreign powers and their representatives (e.g., Pyotr Kozlov and Gustaf Mannerheim), the Dalai Lama showed an interest in world affairs and introduced electricity, the telephone and the first motor cars to Tibet. Nonetheless, at the end of his life in 1933, he saw that Tibet was about to enter a dark age.

References[]

- ↑ Sheel, R. N. Rahul. "The Institution of the Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal, Dharamsala, India. Vol. XIV No. 3. Autumn 1989, p. 28. ISSN 0970-5368

- ↑ "His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso". Namgyal Monastery. http://namgyalmonastery.org/hhdl/hhdl13/. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ↑ Bell (1946); p. 40-41

- ↑ Red Star Travel Guide.

- ↑ Chö-Yang: The Voice of Tibetan Religion and Culture. Year of Tibet Edition, p. 80. 1991. Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

- ↑ Ostrovskaya-Junior, Elena A. Buddhism in Saint Petersburg.

- ↑ French, Patrick. Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, p. 186. (1994). Reprint: Flamingo, London. ISBN 978-0006376019.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri & Pesonen, Ari. (2008) Baron Carl Gustav (Emil) Mannerheim (1867-1951) Kuusankosken Kaupunginkirjasto. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, p. 221. Grove Press, N.Y. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chapman, F. Spencer (1940). Lhasa: The Holy City, p. 137. Readers Union, London. OCLC 10266665

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906)". Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/5iwEyckUo. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ Bell, Charles (1924) Tibet: Past and Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 288.

- ↑ Fergusson, W.N.; Brooke, John W. (1911). Adventure, Sport and Travel on the Tibetan Steppes, preface. Scribner, New York, OCLC 6977261

- ↑ Chapman (1940), p. 141.

- ↑ Chapman (1940), p. 133.

- ↑ French, Patrick. Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, p. 258. (1994). Reprint: Flamingo, London. ISBN 978-0006376019.

- ↑ Chapman (1940).

- ↑ Mayhew, Bradley and Michael Kohn. (2005). Tibet, p. 32. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- ↑ Sheel, R. N. Rahul. "The Institution of the Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal, Vol. XIV No. 3. Autumn 1989, pp. 24 and 29.

- ↑ Sheel, p. 20.

- ↑ Dowman, Keith. (1988). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, p. 49. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Norbu, Thubten Jigme and Turnbull, Colin M. (1968). Tibet: An account of the history, the religion and the people of Tibet. Reprint: Touchstone Books. New York. ISBN 0-671-20559-5, pp. 317-318.

- ↑ Laird (2006), p. 244.

Footnotes[]

| This page uses content from the English Wikisource. The original article was at 13th Dalai Lama. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. As with the Religion wiki, the text of Wikisource is available under the CC-BY-SA. |

- Some text used with permission from www.simhas.org. The author of this text has requested that there appear a direct link to the website on which the information is taken. The original text can be found here: http://www.simhas.org/dalai13.html.

Further reading[]

- Bell, Charles (1946) Portrait of a Dalai Lama: the Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth by Charles Alfred Bell, Sir Charles Bell, Publisher: Wisdom Publications (MA), January 1987, ISBN 9780861710553 (first published as Portrait of the Dalai Lama: London: Collins, 1946).

- Bell, Charles (1924) Tibet: Past and Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Bell, Charles (1931) The Religion of Tibet. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Gelek, Surkhang Wangchen. 1982. "Tibet: The Critical Years (Part 1) "The Thirteenth Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal. Vol. VII, No. 4. Winter 1982, pp. 11–19.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: the demise of the Lamaist state (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) ISBN 978-0-520-07590-0

- Mullin, Glenn H. (2001). The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnation, pp. 376–451. Clear Light Publishers. Santa Fe, New Mexico. ISBN 1-57416-092-3.

- The Wonderful Rosary of Jewels. An official biography compiled for the Tibetan Government, completed in February 1940

| Buddhist titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Trinley Gyatso |

Dalai Lama 1879–1933 Recognized in 1878 |

Succeeded by Tenzin Gyatso |

| |||||||