The Acts of the Apostles (lat. Actus Apostolorum) is a book of the Christian Bible, which now stands fifth in the New Testament. It is commonly referred to as simply Acts. The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Greek Πράξεις ἀποστόλων Praxeis Apostolon) was first used by Irenaeus in the late second century, but some have suggested that the title "Acts" be interpreted as "the Acts of the Holy Spirit" or even "the Acts of Jesus," since 1:1 gives the impression that these acts are set forth as an account of what Jesus continued to do and teach, Jesus himself being the principal actor.[1]

Acts tells the story of the Apostolic Age of the Early Christian church, with particular emphasis on the ministry of the Twelve Apostles and of Paul of Tarsus. The early chapters, set in Jerusalem, discuss Jesus' Resurrection and Great Commission, his Ascension with a prophecy to return, the start of the Twelve Apostles' ministry, and the Day of Pentecost. The later chapters discuss Paul's conversion, his ministry, and finally his arrest and imprisonment and trip to Rome.

It is almost universally agreed that the author of Acts also wrote the Gospel of Luke, see also Luke-Acts. The traditional view is that both books were written c. 60, though most scholars, believing the Gospel to be dependent (at least) on Mark's gospel, view the book(s) as having been written at a later date, sometime between 70 and 100.[2]

'Scholars are about evenly divided on whether [the] attribution to Luke [the companion of Paul] should be accepted as historical ...'.[3]

Content[]

|

|

Summary[]

The author opens with a prologue, usually taken to be addressed to an individual by the name of Theophilus (though this name, which translates literally as "God-lover", may be a nickname rather than a personal appellation) and references "my earlier book"—almost certainly the Gospel of Luke. This is immediately followed by a narrative which is set in Jerusalem.

Peter and the apostles[]

The apostles, along with other followers of Jesus, meet and elect Matthias to replace Judas as a member of The Twelve. On Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends on them. The apostles hear a great wind and witness "tongues of flames" descending on them, paralleling Luke 3:16-17. Thereafter, the apostles have the miraculous power to "speak in tongues" and when they address a crowd, each member of the crowd hears their speech in his own native language.

Peter, along with John, preaches to many in Jerusalem, and performs many miracles such as healings, the casting out of evil spirits, and the raising of the dead. As a result, thousands convert to Early Christianity and are baptized.

As their numbers increase, the Christians begin to be increasingly persecuted. Some of the apostles are arrested and flogged, but ultimately freed. Stephen, one of the first deacons, is arrested for blasphemy, and after a trial, is found guilty and executed by stoning by the Jews, thereby becoming the first known Christian martyr.

Peter and the apostles continue to preach, and Christianity continues to grow, and begins to spread to Gentiles. Peter has a vision in which a voice commands him to eat a variety of impure animals. When Peter objects, the voice replies, "Do not call anything impure that God has made clean." When Peter awakes from his vision, he meets with Cornelius the Centurion, who converts. Peter baptizes the centurion, and later has to justify this decision to the other Christians.

Paul's ministry[]

Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts. He is introduced as a persecutor of the Christian church (8:1:3), until his conversion to Christianity later in the chapter when he encounters the resurrected Christ. His own account of his conversion, Gal 1:11-24, is not detailed. The conversion of Paul on the road to Damascus is told three times. While Paul was on the road to Damascus, near Damascus, "suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4), the light was "brighter than the sun" (26:13) and he was subsequently blinded for three days (9:9). He heard a voice in the Hebrew language (probably Aramaic): "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? ... I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, St. Ananias cured his blindness, "something like scales" fell from his eyes, and baptized him (9:17-19). It is commonly believed that Saul changes his name to Paul at this time, but the source of this claim is unknown, the first mention of another name is later, (13:9), during his first missionary journey.

Several years later, Barnabas and Paul set out on a mission (13-14) to further spread Christianity, particularly among the Gentiles. Paul travels through Asia Minor, preaching and visiting churches throughout the region.

Paul travels to Jerusalem where he meets with the apostles — a meeting known as the Council of Jerusalem (15). Paul's own record of the meeting appears to be Gal 2, however, due to the differences, some argue Gal 2 is a different meeting. Members of the Jerusalem church have been preaching that circumcision is required for salvation. Paul and his associates strongly disagree. After much discussion, James the Just, leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile Christian converts need not follow all of the Mosaic Law, and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised.

The decision of the Council came to be called the Apostolic Decree (Acts 15:19-21) and was that most Jewish law, including the requirement for circumcision of males, was not obligatory for Gentile converts, possibly in order to make it easier for them to join the movement.[4] However, the Council did retain the prohibitions against eating meat containing blood, or meat of animals not properly slain, and against "fornication" and idol worship.[5] Beginning with Augustine of Hippo,[6] many have seen a connection to Noahide Law, while some modern scholars[7] reject the connection to Noahide Law (Genesis 9) and instead see Lev 17-18 as the basis. See also Old Testament Law directed at non-Jews and Leviticus 18. In effect, however, the Jerusalem Church created a double standard: one for Jewish Christians and one for Gentile converts. See Dual-covenant theology for the modern debate.

Paul spends the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor and (some believe) founds his first Christian church in Philippi. Paul then travels to Thessalonica, where he stays for some time before departing for Greece. In Athens, Paul visits an altar with an inscription dedicated to the Unknown God, so when he gives his speech on the Areopagos, he proclaims to worship that same Unknown God whom he identifies as the Christian God.

Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, he was confronted with the rumor of teaching against the Law of Moses (21:21). To prove that he was "living in obedience to the law", Paul took a biblical vow along with some others (21:26). Near the end of the seven days of the vow, Paul was recognized outside Herod's Temple and was nearly beaten to death by a mob, "shouting, 'Men of Israel, help us! This is the man who teaches all men everywhere against our people and our law and this place. And besides, he has brought Greeks into the temple area and defiled this holy place'" (21:28). Paul is rescued from the mob by a Roman commander (21:31-40) and accused of being a revolutionary, "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes", teaching resurrection of the dead, and thus imprisoned in Caesarea (23–26). Paul asserts his right, as a Roman citizen, to be tried in Rome. Paul is sent by sea to Rome, where he spends another two years under house arrest, proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching the "Lord Jesus Christ" (28:30-31). Surprisingly, Acts does not record the outcome of Paul's legal troubles — some traditions hold that Paul was ultimately executed in Rome, while other traditions have him surviving the encounter and later traveling to Spain — see Paul - Imprisonment & Death.

- Universality of Christianity

One of the central themes of Acts, indeed of the New Testament (see also Great Commission) is the universality of Christianity—the idea that Jesus's teachings were for all humanity—Jews and Gentiles alike. In this view, Christianity is seen as a religion in its own right, rather than a subset of Judaism, if one makes the common assumption that Judaism is not universal, however see Noahide Laws and Christianity and Judaism for details. Whereas the members of Jewish Christianity were circumcised and adhered to dietary laws, the Pauline Christianity featured in Acts did not require Gentiles to be circumcised or to obey all of the Mosaic laws, which is consistent with Noahide Law. The final chapter of Acts ends with Paul condemning non-Christian Jews and saying "Therefore I want you to know that God's salvation has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will listen!" (28:28). See also New Covenant (theology).

- Holy Spirit

As in the Gospel of Luke, there are numerous references to the Holy Spirit throughout Acts. Acts features the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" on Pentecost[8] and the subsequent spirit-inspired speaking in tongues. The Holy Spirit is shown guiding the decisions and actions of Christian leaders[9], and the Holy Spirit is said to "fill" the apostles, especially when they preach.[10] As a result, Acts is particularly influential among branches of Christianity which place particular emphasis the Holy Spirit, such as Pentecostalism and the Charismatic movement.

- Attention to the oppressed and persecuted

The Gospel of Luke and Acts both devote a great deal of attention to the oppressed and downtrodden. The impovershed are generally praised,[11] while the wealthy are criticized. Luke-Acts devotes a great deal of attention to women in general[12] and to widows in particular.[13] The Samaritans of Samaria (see map at Iudaea Province), had their temple on Mount Gerizim, and along with some other differences, see Samaritanism, were in conflict with Jews of Judea and Galilee and other regions who had their Temple in Jerusalem and practiced Judaism. Unexpectedly, since Jesus was a Jewish Galilean, the Samaritans are shown favorably in Luke-Acts.[14] In Acts, attention is given to the religious persecution of the early Christians, as in the case of Stephen's martyrdom and the numerous examples are Paul's persecution for his preaching of Christianity.

- Prayer

Prayer is a major motif in both the Gospel of Luke and Acts. Both books have a more prominent attention to prayer than is found in the other gospels.[15] The Gospel of Luke depicts prayer as a certain feature in Jesus's life. Examples of prayer which are unique to Luke include Jesus's prayers at the time of his baptism (Luke 3:21), his praying all night before choosing the twelve (Luke 6:12), and praying for the transfiguration (Luke 9:28). Acts also features an emphasis on prayer and includes a number of notable prayers such as the Believers' Prayer (4:23-31), Stephen's death prayer (7:59-60), and Simon Magus' prayer (8:24). See also Prayer in the New Testament.

- Speeches

Acts features a number of extended speeches or sermons from Peter, Paul, and others. In fact, there are at least 24 different speeches in Acts, and the speeches comprise about 30% of the total verses.[16] These speeches, which are quoted verbatim at length rather than simply summarized, have been the source of debates over the historical accuracy of Acts. (see below).

Authorship[]

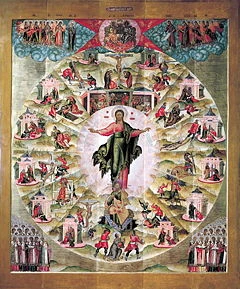

Ministry of the Apostles. Russian icon by Fyodor Zubov, 1660.

While the precise identity of the author is debated, the general consensus is that the author was a Greek Gentile writing for an audience of Gentile Christians.

Common authorship of Luke and Acts[]

There is substantial evidence to indicate that the author of The Gospel of Luke also wrote the Book of Acts. These connections are linked by repeating themes that both of these books share. The most direct evidence comes from the prefaces of each book. Both prefaces are addressed to Theophilus, the author's patron—and perhaps a label for a Christian community as a whole as the name means "Lover of God". Furthermore, the preface of Acts explicitly references "my former book" about the life of Jesus—almost certainly the work we know as The Gospel of Luke.

Furthermore, there are linguistic and theological similarities between the Luke and Acts. As one scholar writes,"the extensive linguistic and theological agreements and cross-references between the Gospel of Luke and the Acts indicate that both works derive from the same author"[17] Because of their common authorship, the Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are often jointly referred to simply as Luke-Acts. Similarly, the author of Luke-Acts is often known as "Luke"—even among scholars who doubt that the author was actually named Luke.

Luke the physician as author[]

The traditional view is that the Gospel of Luke and Acts were written by the physician Luke, a companion of Paul. This Luke is mentioned in Paul's Epistle to Philemon (v.24), and in two other epistles which are traditionally ascribed to Paul (Colossians 4:14 and 2 Timothy 4:11).

The view that Luke-Acts was written by the physician Luke was nearly unanimous in the early Christian church. The Papyrus Bodmer XIV, which is the oldest known manuscript containing the start of the gospel (dating to around 200 AD), uses the title "The Gospel According to Luke". Nearly all ancient sources also shared this theory of authorship—Irenaeus,[18] Tertullian,[19] Clement of Alexandria,[20] Origen, and the Muratorian Canon all regarded Luke as the author of the Luke-Acts. Neither Eusebius of Caesarea nor any other ancient writer mentions another tradition about authorship.

In addition to the authorship evidence provided by the ancient sources, some feel the text of Luke-Acts supports the conclusion that its author was a companion of Paul. First among such internal evidence are portions of the book which have come to be called the "'we' passages". Although the bulk of Acts is written in the third person, several brief sections of the book are written from a first-person perspective.[21] These "we" sections are written from the point of view of a traveling companion of Paul: e.g. "After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia", "We put out to sea and sailed straight for Samothrace"[22] Such passages would appear to have been written by someone who traveled with Paul during some portions of his ministry. Accordingly, some have used this evidence to support the conclusion that these passages, and therefore the entire text of the Luke-Acts, were written by a traveling companion of Paul's. The physician Luke would be one such person.

It has also been argued that level of detail used in the narrative describing Paul's travels suggests an eyewitness source. Some claim that the vocabulary used in Luke-Acts suggests its author may have had medical training, but this claim has been widely disputed.

An anonymous, non-eyewitness author[]

Some modern scholars have expressed doubt that the author of Luke-Acts was the physician Luke.[23] Instead, they believe Luke-Acts was written by an anonymous Christian author who may not have been an eyewitness to any of the events recorded within the text.

Some of the evidence cited comes from the text of Luke-Acts itself. In the preface to Luke, the author refers to having eyewitness testimony "handed down to us" and to having undertaken a "careful investigation", but the author does not mention his own name or explicitly claim to be an eyewitness to any of the events, except for the we passages. And in the we passages, the narrative is written in the first person plural— the author never refers to himself as "I" or "me". To those who are skeptical of an eyewitness author, the we passages are usually regarded as fragments of a second document, part of some earlier account, which was later incorporated into Acts by the later author of Luke-Acts, or simply a Greek rhetorical device used for sea voyages.[24]

Scholars also point to a number of theological and factual discrepancies between Luke-Acts and Paul's letters. For example, Acts and the Pauline letters appear to disagree about the number and timings of Paul's visits to Jerusalem, and Paul's own account of his conversion is slightly different from the account given in Acts. Similarly, some believe the theology of Luke-Acts is slightly different from the theology espoused by Paul in his letters. This might suggest that the author of Luke-Acts did not have direct contact with Paul, but instead may have relied upon other sources for his portrayal of Paul. See also the discussion at Paul of Tarsus.

Also, the "we" passages cannot be used as proof of Lukan authorship. As A.N. Sherwin-White has noted, in travel romance literature of this period, it was a normal literary convention to use the first-person plural while characters were on a shipboard voyage, and "we" passages in Acts coincide with such voyages. B. Witherington and other scholars, however, argue that Acts definitively cannot be classified as 'travel romance' so this argument does not seem to have much power.[25]

A female author of Luke-Acts?[]

Most scholars understand the evangelist's self-referential use of a masculine participle in Luke 1:3 to mean that the evangelist was male, but the prominence of women throughout Luke has led a small number of scholars, such as Randel McCraw Helms, to suggest that the author of Luke-Acts may have been female.[26] In particular, compared to the other canonical gospels, Luke devotes significantly more attention to women. For example, Luke features more female characters, features a female prophet (2:36), and details the experience of pregnancy (1:41-42). However, this could be because Luke was a physician. Prominent discussion is given to the lives of Elizabeth, John the Baptist's mother (ch. 1), and Mary, the mother of Jesus (ch. 2).[27]

Genre[]

The word "Acts" (Greek praxeis) denoted a recognized genre in the ancient world, "characterizing books that described great deeds of people or of cities."[1] There are several such books in the New Testament apocrypha, including the Acts of Thomas, the Acts of Andrew, and the Acts of John.

Modern scholars assign a wide range of genres to the Acts of the Apostles, including biography, novel and epic. Most, however, interpret it as history.[28]

Others have also suggested that the book of Acts may have been written as a legal document wrriten in defence of Paul of Tarsus, for his trial in front of the Emperor in Rome. An event which is spoken of in the book of Acts itself.

Sources[]

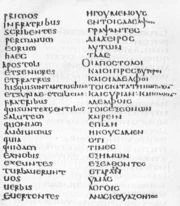

Acts 15:22–24 from the seventh-century Codex Laudianus in the Bodleian Library, written in parallel columns of Latin and Greek.

The author of Acts likely relied upon other sources, as well as oral tradition, in constructing his account of the early church and Paul's ministry. Evidence of this is found in the prologue to the Gospel of Luke, where the author alluded to his sources by writing, "Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word." Some theorize that the "we" passages in Acts are one such "handed down" quotation from some earlier source who was a part of Paul's travels.

It is generally believed that the author of Acts did not have access to a collection of Paul's letters. One piece of evidence suggesting this is that, although half of Acts centers on Paul, Acts never directly quotes from the epistles nor does it even mention Paul writing letters. Additionally, the epistles and Acts disagree about the general chronology of much of Paul's career. Since many of Paul's epistles are believed to be authentic, the discrepancies between the authentic epistles and Acts are probably errors on the part of Acts which were made because its author lacked access to the Pauline epistles or a similar source.

Other theories about Acts' sources are more controversial. Some historians believe that Acts borrows phraseology and plot elements from Euripides' play The Bacchae.[29] Some feel that the text of Acts shows evidence of having used the Jewish historian Josephus as a source (in which case it would have to have been written sometime after 94 AD).[30]

Historicity[]

The question of authorship is largely bound up with that as to the historicity of the contents. Conservative scholars view the book of Acts as being extremely accurate and corroborated by archaeology[31] while skeptics view the work as being inaccurate.[32][33][34]

Evidence for historicity[]

This type of evidence has been assembled by host of scholars.[35] One of them the Roman historian A. N. Sherwin-White concludes: "For Acts, the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming. Yet Acts is, in simple terms and judged externally, no less of a propaganda narrative than the Gospels, liable to similar distortions. But any attempt to reject its basic historicity even in matters of detail must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted."[36]

- The title proconsul (anthypathos) is correctly used for the governors of the two senatorial provinces named in Acts (Acts 13:7-8, Acts 18:12).

- Inscriptions confirm that the city authorities in the Thessalonica in the first century were called politarchs (Acts 17:6,8).

- According to inscriptions, grammateus is the correct title for the chief magistrate in Ephesus (Acts 19:35).

- Felix and Festus are correctly called procurators of Judea. Acts correctly refers to Cornelius as Centurion and to Claudius Lysias as a tribune (Acts 21:31, 23:36)

- Acts 19: 29-41 describe the function of town assemblies in the operation of a city's business. This is characteristic of the first and perhaps early second centuries.

- Inscriptions speak about the prohibition against the Gentiles in the inner areas of the Temple. Acts 21:27-36 presupposes this.

- Roman soldiers were permanently stationed in the tower of Antionia with the responsibility of watching for and suppressing any disturbances at the festivals of the Jews. To reach the affected area they would have to come down a flight of steps into temple precincts. The events of Acts 21:31-37 reflect this.

Evidence against historicity[]

On the other hand, Charles Guignebert, Professor of the History of Christianity in the Sorbonne, asserts that "it has been established that the author of Acts was ignorant of the epistles of Paul, and even formally contradicts them; that he does not understand certain ancient traditions [e.g. glossolalia]; and above all that his narrative of the first years of the history of the Christian Church, whose founders he is supposed to have known intimately, is pitifully inadequate" [37]

- Acts 5:33-39 gives an account of speech by the first century Pharisee Gamaliel, in which he refers to two movements other than the Way. One lead by Theudas (v 36) and after him led by Judas the Galilean. Josephus placed Judas about 6 AD. He places Theudas under the procurator Fadus 44-46 AD. Two problems emerge. First, the order of Judas and Theudas is reversed in Acts 5. Second, Theudas's movement comes after the time when Gamaliel is speaking.

- In Acts 9:31 which says "So the church throughout all Judea and Galilea and Samaria had peace and was built up" has been taken to mean that Judea was understood to have been directly connected to Galilee. If so, then Luke had an incorrect understanding of Palestinian Geography.

- In Acts 23:31, says the soldiers brought Paul from Jerusalem to Antipatris, a distance of some 45 miles, overnight. Thirty miles constituted a suitable days journey whether by land or by sea. Both the numbers involved (two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, two hundred spearmen) and the speed of the journey (38 to 45 miles in a night) are exaggerated to emphasize the importance of person being accompanied and the extent of the danger.

- Acts 11:28 and 12:25 speaks of a famine under Claudius (41-54 AD). The famine is mentioned in Acts before the death of Herod (12:20-23. Josephus mentions a famine in Jerusalem relieved by the good graces of Queen Helena of Adiabene connected with procuratorship of Tiberius Julius Alexander (46-48 AD). Josephus however locates the famine after the death of Herod. Agabus' prophecy is therefore not precisely placed in the sequences of Acts 11:28.

- It seems very strange that Luke could know what Festus and Agrippa said to each other in their private apartments (Acts 25:13-22, 26:30-32) or what the members of the Sanhedrin said in a closed session (Acts 4:15-17, 5:34-40)

Content[]

Acts is divided into two distinct parts. The first (chs. 1–12) deals with the church in Jerusalem and Judaea, and with Peter as central figure—at any rate in the first five chapters. "Yet in cc. vi.-xii.," as Harnack observes,

the author pursues several lines at once. (1) He has still in view the history of the Jerusalem community and the original apostles (especially of Peter and his missionary labors); (2) he inserts in vi. 1 ff. a history of the Hellenistic Christians in Jerusalem and of the Seven Men, which from the first tends towards the Gentile Mission and the founding of the Antiochene community; (3) he pursues the activity of Philip in Samaria and on the coast...; (4) lastly, he relates the history of Paul up to his entrance on the service of the young Antiochene church. In the small space of seven chapters he pursues all these lines and tries also to connect them together, at the same time preparing and sketching the great transition of the Gospel from Judaism to the Greek world. As historian, he has here set himself the greatest task.

No doubt gaps abound in these seven chapters. "But the inquiry as to whether what is narrated does not even in these parts still contain the main facts, and is not substantially trustworthy, is not yet concluded." The difficulty is that there are few external means of testing this portion of the narrative. The second part pursues the history of the apostle Paul, and here the statements made in the Acts may be compared with the Epistles. The result is a general harmony, without any trace of direct use of these letters; and there are many minute coincidences. But attention has been drawn to two remarkable exceptions: the account given by Paul of his visits to Jerusalem in Galatians as compared with Acts; and the character and mission of the apostle Paul, as they appear in his letters and in Acts.

In regard to the first point, the differences as to Paul's movements until he returns to his native province of Syria-Cilicia do not really amount to more than can be explained by the different interests of Paul and the author, respectively. But it is otherwise as regards the visits of Galatians 2:1-10 and Acts 15. If they are meant to refer to the same occasion, as is usually assumed, it is hard to see why Paul should omit reference to the public occasion of the visit, as also to the public vindication of his policy. But in fact the issues of the two visits, as given in Galatians 2:9f. and Acts 15:20f., are not at all the same. Nay more, if Galatians 2:1–10 = Acts 15, the historicity of the "Relief visit" of Acts 11:30, 12:25 seems definitely excluded by Paul's narrative of events before the visit of Galatians 2:1ff. Accordingly, Sir W. M. Ramsay and others argue that the latter visit itself coincided with the Relief visit, and even see in Galatians 2:10 witness thereto.

But why does not Paul refer to the public charitable object of his visit? It seems easier to assume that the visit of Galatians 2:1ff. is altogether unrecorded in Acts, owing to its private nature as preparing the way for public developments—with which Acts is mainly concerned. In that case, it would fall shortly before the Relief visit, to which there may be tacit explanatory allusion, in Galatians 2:10; and it will be shown below that such a conference of leaders in Galatians 2:1ff. leads up excellently both to the First Mission Journey and to Acts 15.

As for Paul as depicted in Acts, Paul claims that he was appointed the apostle to the Gentiles, as Peter was to the Circumcision; and that circumcision and the observance of the Mosaic Law were of no importance to the Gentile Christian as such. His words on these points in all his letters are strong and decided, but see also Antinomianism and New Perspective on Paul. But in Acts, it is Peter who first opens up the way for the Gentiles. It is Peter who uses the strongest language in regard to the intolerable burden of the Law as a means of salvation (15:10f.; cf. 1), so-called Legalism (theology). Not a word is said of any difference of opinion between Peter and Paul at Antioch (Gal 2:11ff.). The brethren in Antioch send Paul and Barnabas up to Jerusalem to ask the opinion of the apostles and elders: they state their case, and carry back the decision to Antioch. Throughout the whole of Acts, Paul never stands forth as the unbending champion of the Gentiles. He seems continually anxious to reconcile the Jewish Christians to himself by personally observing the law of Moses. He personally circumcises the semi-Jew, Timothy (Acts 16:1-4); and he performs his vows in the temple (Acts 21:26). He is particularly careful in his speeches to show how deep is his respect for the law of Moses (Acts 24:14-15). In all this, the letters of Paul are very different from Acts. In Galatians, he claims perfect freedom in principle, for himself as for the Gentiles, from the obligatory observance of the law, see also Antinomianism; and neither in it nor in Corinthians does he take any notice of a decision to which the apostles had come in their meeting at Jerusalem. The narrative of Acts, too, itself implies something other than what it sets in relief; for why should the Jews hate Paul so much, if he was not in some sense disloyal to their Law?

According to historian Colin J. Hemer,[38] This is not necessarily a contradiction; only such a difference of emphasis as belongs to the standpoints and aims of the two writers amid their respective historical conditions. Peter's function toward the Gentiles belongs to early conditions present in Judaea, before Paul's distinctive mission had taken shape. Once Paul's apostolate—a personal one, parallel with the more collective apostolate of "the Twelve"—has proved itself by tokens of Divine approval, Peter and his colleagues frankly recognize the distinction of the two missions, and are anxious only to arrange that the two shall not fall apart by religiously and morally incompatible usages (Acts 15). Paul, on his side, clearly implies that Peter felt with him that the Law could not justify (Gal 2:15ff.), and argues that it could not now be made obligatory in principle (cf. "a yoke," Acts 15:10); yet for Jews it might continue for the time (pending the Parousia) to be seemly and expedient, especially for the sake of non-believing Judaism. To this he conformed his own conduct as a Jew, so far as his Gentile apostolate was not involved (1 Cor 9:19-23). There is no reason to doubt that Peter largely agreed with him, since he acted in this spirit in Galatians 2:11f., until coerced by Jerusalem sentiment to draw back for expediency's sake. This incident simply did not fall within the scope of Acts to narrate, since it had no abiding effect on the Church's extension. As to Paul's submission of the issue in Acts 15 to the Jerusalem conference, Acts does not imply that Paul would have accepted a decision in favor of the Judaizers, though he saw the value of getting a decision for his own policy in the quarter where they were most likely to defer. If the view that he already had an understanding with the "Pillar" Apostles, as recorded in Galatians 2:1–10, be correct, it gives the best of reasons why he was ready to enter the later public Conference of Acts 15. Paul's own "free" attitude to the Law, when on Gentile soil, is just what is implied by the hostile rumors as to his conduct in Acts 21:21, which he would be glad to disprove as at least exaggerated (vv. 24 and 26).

Speeches[]

The speeches in Acts deserve special notice, because they constitute about 20% of the entire book. Given the nature of the times, lack of recording devices, and space limitations, many ancient historians did not reproduce verbatim reports of speeches. Condensing and using one's own style was often unavoidable. Nevertheless, there were different practices when it came to the level of creativity or adherence individual historians practiced.

On one end of the scale were those who seemingly invented speeches, such as the Sicilian historian Timaeus (356–260 BC). Others, such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Tacitus, fell somewhere in between, reporting actual speeches but likely with significant liberty. The ideal for ancient historians, however, seems to have been to try as much as possible to report the sense of what was actually said, rather than simply placing one's own speech in a figure's mouth.

Perhaps the best example of this ideal was voiced by Polybius, who ridiculed Timaeus for his invention of speeches. Historians, Polybius wrote, were "to instruct and convince for all time serious students by the truth of the facts and the speeches he narrates" (Hist. 2.56.10–12). Another ancient historian, Thucydides, admits to having taken some liberty while narrating speeches, but only when he did not have access to any sources. When he had sources, he used them. In his own words, Thucydides wrote speeches "of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said" (History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.22.1). Accordingly, as stated by C.W. Fornara, "[t]he principle was established that speeches were to be recorded accurately, though in the words of the historian, and always with the reservation that the historian could 'clarify'" (The Nature of History in Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 145).

On what end of the scale did the author of Acts fall? There is little doubt that the speeches of Acts are summaries or condensations largely in the style and vocabulary of its author. However, there are indications that the author of Acts relied on source material for his speeches, and did not treat them as mere vehicles for expressing his own theology. The author's apparent use of speech material in the Gospel of Luke, obtained from the Gospel of Mark and the hypothetical Q document or the Gospel of Matthew, suggests that he relied on other sources for his narrative and was relatively faithful in using them. Additionally, many scholars have viewed Acts' presentation of Stephen's speech, Peter's speeches in Jerusalem and, most obviously, Paul's speech in Miletus as relying on source material or of expressing views not typical of Acts' author.[39] Additionally, there is no evidence that any speech in Acts is the free composition of its author, without either written or oral basis. Accordingly, in general, the author of Acts seems to be among the conscientious ancient historians, touching the essentials of historical accuracy, even as now understood. Or, according to Encyclopedia Biblica, "it is beyond doubt that the author constructed them in each case according to his own conception of the situation."[40]

Structure[]

The structure of the book of Luke[41] is closely tied with the structure of Acts.[42] Both books are most easily tied to the geography of the book. Luke begins with a global perspective, dating the birth of Jesus to the reign of the Roman emperors in Luke 2:1 and 3:1. From there we see Jesus' ministry move from Galilee (chapters 4–9), through Samaria and Judea (chs. 10–19), to Jerusalem where he is crucified, raised and ascended into heaven (chs. 19–24). The book of Acts follows just the opposite motion, taking the scene from Jerusalem (chs. 1–5), to Judea and Samaria (chs. 6–9), then traveling through Syria, Asia Minor, and Europe towards Rome (chs. 9–28). This chiastic structure emphasizes the centrality of the resurrection and ascension to Luke's message, while emphasizing the universal nature of the gospel.

This geographic structure is foreshadowed in Acts 1:8, where Jesus says "You shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem (chs. 1–5), and in all Judea and Samaria (chs. 6–9), and even to the remotest part of the earth (chs. 10–28)." The first two sections (chs. 1–9) represent the witness of the apostles to the Jews, while the last section (chs. 10–28) represent the witness of the apostles to the Gentiles.

The book of Acts can also be broken down by the major characters of the book. While the complete title of the book is the Acts of the Apostles, really the book focuses on only two of the apostles: Peter (chs. 1–12) and Paul (chs. 13–28).

Within this structure, the sub-points of the book are marked by a series of summary statements, or what one commentary calls a "progress report". Just before the geography of the scene shifts to a new location, Luke summarizes how the gospel has impacted that location. The standard for these progress reports is in 2:46–47, where Luke describes the impact of the gospel on the new church in Jerusalem. The remaining progress reports are located:

- Acts 6:7 Impact of the gospel in Jerusalem.

- 9:31 Impact of the gospel in Judea and Samaria.

- 12:24 Impact of the gospel in Syria.

- 16:5 Impact of the gospel in Asia Minor.

- 19:20 Impact of the gospel in Europe.

- 28:31 Impact of the gospel on Rome.

This structure can be also seen as a series of concentric circles, where the gospel begins in the center, Jerusalem, and is expanding ever outward to Judea & Samaria, Syria, Asia Minor, Europe, and eventually to Rome.

Date[]

Traditionally the book of Acts has been dated in the second half of the first century, though some scholars now regard an early 2nd century origin more likely. At one extreme, Norman Geisler dates it as early as between 60-62.[43] Donald Guthrie noted that the absence of any mention of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 would be unlikely if the book were written afterwards. He also suggested that since the book does not mention the death of Paul, a central character in the final chapters, it was likely penned before his death.[44]. Guthrie also saw traces of Acts in Polycarp's letter to the Philippians (written between 110-140) and one letter by Ignatius († before 117)[45] and thought that Acts probably was current in Antioch and Smyrna not later than circa 115, and perhaps in Rome as early as circa 96. [46] Another argument used in favor of a 1st century origin of Acts is the suggested absence of clear references to Paul's Epistles.

On the other hand, the lack of a mention of the destruction of Jerusalem is also used as an argument for a later date, well beyond 70, while the prologue to Luke's Gospel itself implies the dying out of the generation of eyewitnesses as a class. The Tübingen school and its heirs suggested a date in the early 2nd century, partially on observing traces of 2nd century Gnosticism, "hierarchical" ideas of organization, and in light of the relation of the Roman state to the Christians, though William Ramsey used the latter instead to suggest an origin prior to Pliny's correspondence with Trajan on the subject in the year 100. Parallels have long been observed between Acts and Josephus' The Wars of the Jews (written in 75-80) and Antiquities of the Jews of 94 AD.[47] Several scholars have strongly argued that Acts used material of both of Josephus' works, rather than the other way around, which would indicate that Acts was written around the year 100 or later.[47][48][49] It has also been pointed out that no ancient source actually mentions Acts by name prior to 177.

Place[]

The place of composition is still an open question. For some time Rome and Antioch have been in favor, and Blass combined both views in his theory of two editions. But internal evidence points strongly to the Roman province of Asia, particularly the neighborhood of Ephesus. Note the confident local allusion in 19:9 to "the school of Tyrannus" and in 19:33 to "Alexander"; also the very minute topography in 20:13–15. At any rate affairs in that region, including the future of the church of Ephesus (20:28–30), are treated as though they would specially interest "Theophilus" and his circle; also an early tradition makes Luke die in the adjacent Bithynia. Finally it was in this region that there arose certain early glosses (e.g., 19:9; 20:15), probably the earliest of those referred to below. How fully in correspondence with such an environment the work would be, as apologia for the Church against the Synagogue's attempts to influence Roman policy to its harm, must be clear to all familiar with the strength of Judaism in Asia (cf. Rev 2:9, 3:9; and see Sir W. M. Ramsay, The Letters to the Seven Churches, ch. xii.).

Manuscripts[]

Like most biblical books, there are differences between the earliest surviving manuscripts of Acts. In the case of Acts, however, the differences between the surviving manuscripts is more substantial. The two earliest versions of manuscripts are the Western text-type (as represented by the Codex Bezae) and the Alexandrian text-type (as represented by the Codex Sinaiticus). The version of Acts preserved in the Western manuscripts contains about 10% more content than the Alexandrian version of Acts. Since the difference is so great, scholars have struggled to determine which of the two versions is closer to the original text composed by the original author.

The earliest explanation, suggested by Swiss theologian Jean LeClerc in the 17th century, posits that the longer Western version was a first draft, while the Alexandrian version represents a more polished revision by the same author. Adherents of this theory argue that even when the two versions diverge, they both have similarities in vocabulary and writing style-- suggesting that the two shared a common author. However, it has been argued that if both texts were written by the same individual, they should have exactly identical theologies and they should agree on historical questions. Since most modern scholars do detect subtle theological and historical differences between the texts, most scholars do not subscribe to the rough-draft/polished-draft theory.

A second theory assumes common authorship of the Western and Alexandrian texts, but claims the Alexandrian text is the short first draft, and the Western text is a longer polished draft. A third theory is that the longer Western text came first, but that later, some other redactor abbreviated some of the material, resulting in the shorter Alexandrian text.

While these other theories still have a measure of support, the modern consensus is that the shorter Alexandrian text is closer to the original, and the longer Western text is the result of later insertion of additional material into the text.[50] Already in 1893, Sir W. M. Ramsay in The Church in the Roman Empire held that the Codex Bezae (the Western text) rested on a recension made in Asia Minor (somewhere between Ephesus and southern Galatia), not later than about the middle of the 2nd century. Though "some at least of the alterations in Codex Bezae arose through a gradual process, and not through the action of an individual reviser," the revision in question was the work of a single reviser, who in his changes and additions expressed the local interpretation put upon Acts in his own time. His aim, in suiting the text to the views of his day, was partly to make it more intelligible to the public, and partly to make it more complete. To this end he "added some touches where surviving tradition seemed to contain trustworthy additional particulars," such as the statement that Paul taught in the lecture-room of Tyrannus "from the fifth to the tenth hour" (added to Acts 19:9). In his later work, St Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen (1895), Ramsay's views gain both in precision and in breadth. The gain lies chiefly in seeing beyond the Bezan text to the "Western" text as a whole.

It is believed that the material in the Western text which isn't in the Alexandrian text reflects later theological developments within Christianity. For examples, the Western text features a greater hostility to Judaism, a more positive attitude towards a Gentile Christianity, and other traits which appear to be later additions to the text. Some also note that the Western text attempts to minimize the emphasis Acts places on the role of women in the early Christian church.[51]

A third class of manuscripts, known as the Byzantine text-type, is often considered to have developed after the Western and Alexandrian types. While differing from both of the other types, the Byzantine type has more similarity to the Alexandrian than to the Western type. The extant manuscripts of this type date from the 5th century or later; however, papyrus fragments show that this text-type may date as early as the Alexandrian or Western text-types.[52] The Byzantine text-type served as the basis for the 16th century Textus Receptus, the first Greek-language version of the New Testament to be printed by printing press. The Textus Receptus, in turn, served as the basis for the New Testament found in the English-language King James Bible. Today, the Byzantine text-type is the subject of renewed interest as the possible original form of the text from which the Western and Alexandrian text-types were derived.[53]

See also[]

- List of Gospels

- Textual variants in the Acts of the Apostles

- List of omitted Bible verses

Acts of the Apostles (genre)

- Acts of Andrew

- Acts of Barnabas

- Acts of John

- The Lost Chapter of the Acts of the Apostles

- Acts of the Martyrs

- Acts of Paul

- Acts of Peter

- Acts of Peter and Paul

- Acts of Peter and the Twelve

- Acts of Philip

- Acts of Pilate

- Acts of Thecla

- Acts of Thomas

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carson, D. A., Moo, Douglas J. and Morris, Leon An Introduction to the New Testament (Leicester: Apollos, 1999), 181.

- ↑ Refers to Markan Priority as "The Dominant View". The Making of Mark By Harold Riley, pg vii

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. (1997). Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. pp. 267–8. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- ↑ Acts 15:19

- ↑ Karl Josef von Hefele's Commentary on canon II of Gangra notes: "We further see that, at the time of the Synod of Gangra, the rule of the Apostolic Synod with regard to blood and things strangled was still in force. With the Greeks, indeed, it continued always in force as their Euchologies still show. Balsamon also, the well-known commentator on the canons of the Middle Ages, in his commentary on the sixty-third Apostolic Canon, expressly blames the Latins because they had ceased to observe this command. What the Latin Church, however, thought on this subject about the year 400, is shown by St. Augustine in his work Contra Faustum, where he states that the Apostles had given this command in order to unite the heathens and Jews in the one ark of Noah; but that then, when the barrier between Jewish and heathen converts had fallen, this command concerning things strangled and blood had lost its meaning, and was only observed by few. But still, as late as the eighth century, Pope Gregory the Third 731 forbade the eating of blood or things strangled under threat of a penance of forty days. No one will pretend that the disciplinary enactments of any council, even though it be one of the undisputed Ecumenical Synods, can be of greater and more unchanging force than the decree of that first council, held by the Holy Apostles at Jerusalem, and the fact that its decree has been obsolete for centuries in the West is proof that even Ecumenical canons may be of only temporary utility and may be repealed by disuser, like other laws."

- ↑ Contra Faust, 32.13

- ↑ For example: Joseph Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles (The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries), Yale University Press (December 2, 1998), ISBN 0300139829, chapter V

- ↑ Acts 1:5, 8; 2:1-4; 11:15-16 according to here [1]

- ↑ Acts 15:28; 16:6-7; 19:21; 20:22-23 according to here

- ↑ Acts 1:8; 2:4; 4:8, 31; 11:24; 13:9, 52 according to here

- ↑ e.g. "Preach good news to the poor" (Luke 4:18), "Blessed are the poor" (Luke 6:20–21), Luke's Attitude Towards Rich and Poor

- ↑ Luke 1, Luke 2

- ↑ Luke 2:37; 4:25-26; 7:12; 18:3, 5; 20:47; 21:2-3)

- ↑ e.g. the good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37), the story of the Samaritan who expressed gratitude to Jesus for being healed (Luke 17:11-19), and the entrance of the Samaritans into the church of God (Acts 8:4-25).

- ↑ Theology of prayer in the gospel of Luke

- ↑ Listed here

- ↑ (Udo Schnelle, The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, p. 259).

- ↑ (Haer. 3.1.1, 3.14.1)

- ↑ (Marc. 4.2.2)

- ↑ (Paedagogus 2.1.15 and Stromata 5.12.82)

- ↑ Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, and 27:1–28:16

- ↑ Acts 16:10

- ↑ For example, see Catholic Encyclopedia: Acts of the Apostles: OBJECTIONS AGAINST THE AUTHENTICITY: "Nevertheless this well-proved truth has been contradicted. Baur, Schwanbeck, De Wette, Davidson, Mayerhoff, Schleiermacher, Bleek, Krenkel, and others have opposed the authenticity of the Acts. An objection is drawn from the discrepancy between Acts ix, 19-28 and Gal., i, 17, 19. In the Epistle to the Galatians, i, 17, 18, St. Paul declares that, immediately after his conversion, he went away into Arabia, and again returned to Damascus. "Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas." In Acts no mention is made of St. Paul's journey into Arabia; and the journey to Jerusalem is placed immediately after the notice of Paul's preaching in the synagogues. Hilgenfeld, Wendt, Weizäcker, Weiss, and others allege here a contradiction between the writer of the Acts and St. Paul." Note that the Catholic Encyclopedia considers the authenticity of Acts to be a "well-proved truth" but nonetheless notes that other scholars disagree.

- ↑ Robbins, Vernon. "Perspectives on Luke-Acts", http://www.christianorigins.com/bylandbysea.html. Originally appeared in: Perspectives on Luke-Acts. C. H. Talbert, ed. Perspectives in Religious Studies, Special Studies Series, No. 5. Macon, Ga: Mercer Univ. Press and Edinburgh: T.& T. Clark, 1978: 215-242.

- ↑ Witherington B., The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Carlisle: Paternoster Press 1998, 22-23, 53-54, 480ff

- ↑ Randel McCraw Helms (1997) Who Wrote The Gospels? ISBN 0-9655047-2-7, Millennium Press

- ↑ The Prominence of Women in the Gospel of Luke

- ↑ Phillips, Thomas E. "The Genre of Acts: Moving Toward a Consensus?" Currents in Biblical Research 4 [2006] 365 - 396.

- ↑ Randel McCram Helms (1997) Who Wrote The Gospels

- ↑ Luke and Josephus

- ↑ The Book of Acts & Archeology

- ↑ The Historical Reliability of Acts

- ↑ The Fictitious Speeches in Acts

- ↑ Are the Gospels Eyewitness Accounts?

- ↑ Reading Acts By Charles H. Talbert

- ↑ A. N. Sherwin-White, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), p. 189.

- ↑ Jesus, Translated from the French by S. H. Hooke, Professor of Old Testament Studies, University of London, University Books, New York, 1956.

- ↑ Questions and evidence of historicity are presented in Colin J. Hemer, "The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History", Eisenbrauns, 1990

- ↑ Christian CADRE-Speeches in Acts

- ↑ "Acts", Encyclopedia Biblica

- ↑ See, for example, Gooding, David W., According to Luke, (1987) ISBN 0-85110-756-7

- ↑ See, for example, Gooding, David W., True to the Faith, (1990) ISBN 0-340-52563-0

- ↑ "The Dating of the New Testament". bethinking.org. http://www.bethinking.org/resource.php?ID=233. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Guthrie, Donald. "Nine". New Testament Introduction (third ed.). Downer's Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. pp. 340–345. ISBN 0-87784-953-6.

- ↑ The suggested traces can be found at Ignatius and Polycarp.

- ↑ Guthrie, Donald. "Nine". New Testament Introduction (third ed.). Downer's Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. pp. 347–348. ISBN 0-87784-953-6.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Richard Carrier, Luke and Josephus (2000)

- ↑ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament, Hendrickson Publishers: Peabody, Massachusetts, 1992, pp. 185-229

- ↑ Robert Eisenman makes a strong case for Acts using material from Josephus in his Cal State lecture series on the historical Jesus, his book James the Brother of Jesus and other of his works.

- ↑ The Text of Acts

- ↑ The influence on the Textus Receptus and the KJV of the Western Text's "anti-feminist bias"

- ↑ Such as P66 and P75. See: E. C. Colwell, Hort Redivisus: A Plea and a Program, Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the New Testament, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969, p. 45-48.

- ↑ See: Robinson, Maurice A. and Pierpont, William G., The New Testament in the Original Greek, (2005) ISBN 0-7598-0077-4

| This Creative Commons Licensed page uses content from Wikipedia (view authors). The text of Wikipedia is available under the license Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (ToU). |