- "Masse" redirects here. For the surname, see Massé. For the billiards technique, see Massé.

Masei, Mas’ei, or Masse (מסעי — Hebrew for “journeys,” the second word, and the first distinctive word, in the parshah) is the 43rd weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the 10th and last in the book of Numbers. It constitutes Numbers 33:1–36:13. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in July or August.

The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2011 and 2014), parshah Masei is read separately. In common years (for example, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017), parshah Masei is combined with the previous parshah, Matot, to help achieve the number of weekly readings needed.

Encampment of Israelites, Mount Sinai (1836 intaglio print after J. M. W. Turner from Landscape illustrations of the Bible)

Summary[]

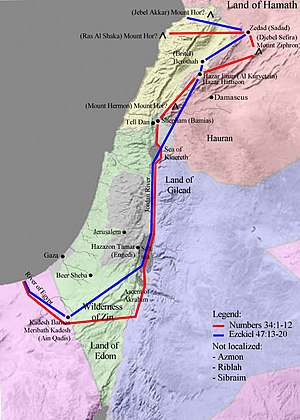

The Land of Israel as defined in Numbers 34:1–12

Stations of the Israelites’ journeys[]

Moses recorded the various journeys of the Israelites from the land of Egypt as directed by God as follows: They journeyed from Rameses to Sukkoth to Etham to Pi-hahiroth to Marah to Elim to the Sea of Reeds to the wilderness of Sin to Dophkah to Alush to Rephidim to the wilderness of Sinai to Kibroth-hattaavah to Hazeroth to Rithmah to Rimmon-perez to Libnah to Rissah to Kehelath to Mount Shepher Haradah to Makheloth to Tahath to Terah to Mithkah to Hashmonah to Moseroth to Bene-jaakan to Hor-haggidgad to Jotbath to Abronah to Ezion-geber to Kadesh to Mount Hor. (Numbers 33:1–37.) At God's command, Aaron ascended Mount Hor and died there, at the age of 123 years. (Numbers 33:38–39.) They journeyed from Mount Hor to Zalmonah to Punon to Oboth to Iye-abarim to Dibon-gad to Almon-diblathaim to the hills of Abarim to the steppes of Moab. (Numbers 33:41–49.)

Instructions for taking the land[]

In the steppes of Moab, God told Moses to direct the Israelites that when they crossed the Jordan into Canaan, they were to dispossess all the inhabitants of the land, destroy all their figured objects, molten images, and cult places, and take possession of and settle in the land. (Numbers 33:50–53.) They were to apportion the land among themselves by lot, clan by clan, with the share varying with the size of the group. (Numbers 33:54.) But God warned that if the Israelites did not dispossess the inhabitants of the land, those whom they allowed to remain would become stings in their eyes and thorns in their sides, and would harass the Israelites in the land, so that God would do to the Israelites what God had planned to do to the inhabitants of the land. (Numbers 33:55–56.) God then told Moses to instruct the Israelites in the boundaries of the land, which included the Dead Sea, the wilderness of Zin, the Wadi of Egypt, the Mediterranean Sea, Mount Hor, the eastern slopes of the Sea of Galilee, and the River Jordan. (Numbers 34:1–12.) Moses instructed the Israelites that the tribe of Reuben, the tribe of Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh had received their portions across the Jordan. (Numbers 34:13–15.) God told Moses the names of the men through whom the Israelites were to apportioned the land: Eleazar, Joshua, and a chieftain named from each tribe. (Numbers 34:16–29.)

Cities for the Levites and refuge[]

Cities of Refuge (illustration from a Bible card published 1901 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

God told Moses to instruct the Israelites to assign the Levites out of the other tribes’ holdings towns and pasture land for 2,000 cubits outside the town wall in each direction. (Numbers 35:1–5.) The Israelites were to assign the Levites 48 towns in all, of which 6 were to be cities of refuge to which a manslayer could flee. (Numbers 35:6–7.) The Israelites were to take more towns from the larger tribes and fewer from the smaller. (Numbers 35:8.) Three of the six cities of refuge were to be designated east of the Jordan, and the other three were to be designated in the land of Canaan. (Numbers 35:14.)

The cities of refuge were to serve as places to which a slayer who had killed a person unintentionally could flee from the avenger, so that the slayer might not die without a trial before the assembly. (Numbers 35:9–12.) Anyone, however, who struck and killed another with an iron object, stone tool, or wood tool was to be considered a murderer, and was to be put to death. (Numbers 35:16–18.) The blood-avenger was to put the murderer to death upon encounter. (Numbers 35:19.) Similarly, if the killer pushed or struck the victim by hand in hate or hurled something at the victim on purpose and death resulted, the assailant was to be put to death as a murderer. (Numbers 35:20–21.) But if the slayer pushed the victim without malice aforethought, hurled an object at the victim unintentionally, or inadvertently dropped on the victim any deadly object of stone, and death resulted — without the victim being an enemy of the slayer and without the slayer seeking the victim harm — then the assembly was to decide between the slayer and the blood-avenger. (Numbers 35:22–24.) The assembly was to protect the slayer from the blood-avenger, and the assembly was to restore the slayer to the city of refuge to which the slayer fled, and there the slayer was to remain until the death of the high priest. (Numbers 35:25.) But if the slayer ever left the city of refuge, and the blood-avenger came upon the slayer outside the city limits, then there would be no bloodguilt if the blood-avenger killed the slayer. (Numbers 35:26–27.) The slayer was to remain inside the city of refuge until the death of the high priest, after which the slayer could return to his land. (Numbers 35:28.) A slayer could be executed only on the evidence of more than one witness. (Numbers 35:30.) The Israelites were not to accept a ransom for the life of a murderer guilty of a capital crime; the murderer was to be put to death. (Numbers 35:31.) Similarly, the Israelites were not to accept ransom in lieu of flight to a city of refuge, enabling a slayer to return to live on the slayer's land before the death of the high priest. (Numbers 35:32.) Bloodshed polluted the land, and only the blood of the one who shed it could make expiation for the bloodshed. (Numbers 35:33.)

The Daughters of Zelophehad (illustration from the 1908 Bible and Its Story Taught by One Thousand Picture Lessons)

The daughters of Zelophehad[]

Kinsmen of Zelophehad, a man of the tribe of Manasseh who had died without a son (see Numbers 27:1–11 and parshat Pinchas), appealed to Moses and the chieftains regarding Zelophehad's daughters, to whom God had commanded Moses to assign land. (Numbers 36:1–2.) Zelophehad's kinsmen expressed the concern that if Zelophehad's daughters married men from another Israelite tribe, their land would be cut off from Manasseh's ancestral portion and be added to the portion of the husbands’ tribe. (Numbers 36:3.) At God's bidding, Moses instructed the Israelites that the daughters of Zelophehad could marry only men from their father's tribe, so that no inheritance would pass from one tribe to another. (Numbers 36:6–7.) And Moses announced the general rule that every daughter who inherited a share was required to marry someone from her father's tribe, in order to preserve each tribe's ancestral share. (Numbers 36:8–9.) The daughters of Zelophehad did as God had commanded Moses, and they married cousins, men of the tribe of Manasseh. (Numbers 36:10–12.)

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

Numbers chapter 35[]

Chapter 2 of tractate Makkot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the cities of refuge in Exodus 21:12–14, Numbers 35:1–34, Deuteronomy 4:41–43, and 19:1–13. (Mishnah Makkot 2:1–8; Tosefta Makkot 2:1–3:10; Jerusalem Talmud Makkot; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 7a–13a.)

The Mishnah taught that those who killed in error went into banishment. One would go into banishment if, for example, while one was pushing a roller on a roof, the roller slipped over, fell, and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while one was lowering a cask, it fell down and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while coming down a ladder, one fell and killed someone. But one would not go into banishment if while pulling up the roller it fell back and killed someone, or while raising a bucket the rope snapped and the falling bucket killed someone, or while going up a ladder one fell down and killed someone. The Mishnah's general principle was that whenever the death occurred in the course of a downward movement, the culpable person went into banishment, but if the death did not occur in the course of a downward movement, the person did not go into banishment. If while chopping wood, the iron slipped from the ax handle and killed someone, Rabbi taught that the person did not go into banishment, but the sages said that the person did go into banishment. If from the split log rebounding killed someone, Rabbi said that the person went into banishment, but the sages said that the person did not go into banishment. (Mishnah Makkot 2:1; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 7a–b.)

Rabbi Jose bar Judah taught that to begin with, they sent a slayer to a city of refuge, whether the slayer killed intentionally or not. Then the court sent and brought the slayer back from the city of refuge. The Court executed whomever the court found guilty of a capital crime, and the court acquitted whomever the court found not guilty of a capital crime. The court restored to the city of refuge whomever the court found liable to banishment, as Numbers 35:25 ordained, “And the congregation shall restore him to the city of refuge from where he had fled.” (Mishnah Makkot 2:6; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 9b.) Numbers 35:25 also says, “The manslayer . . . shall dwell therein until the death of the high priest, who was anointed with the holy oil,” but the Mishnah taught that the death of a high priest who had been anointed with the holy anointing oil, the death of a high priest who had been consecrated by the many vestments, or the death of a high priest who had retired from his office each equally made possible the return of the slayer. Rabbi Judah said that the death of a priest who had been anointed for war also permitted the return of the slayer. Because of these laws, mothers of high priests would provide food and clothing for the slayers in cities of refuge so that the slayers might not pray for the high priest's death. (Mishnah Makkot 2:6; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 11a.) If the high priest died at the conclusion of the slayer's trial, the slayer did not go into banishment. If, however, the high priests died before the trial was concluded and another high priest was appointed in his stead and then the trial concluded, the slayer returned home after the new high priest's death. (Mishnah Makkot 2:6; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 11b.)

Numbers chapter 36[]

Chapter 8 of tractate Bava Batra in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and chapter 7 of tractate Bava Batra in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of inheritance in Numbers 27:1–11 and 36:1–9. (Mishnah Bava Batra 8:1–8; Tosefta Bava Batra 7:1–18; Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 108a–39b.)

A Baraita taught that Zelophehad's daughters were wise, Torah students, and righteous. (Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 119b.) And a Baraita taught that Zelophehad's daughters were equal in merit, and that is why the order of their names varies between Numbers 27:1 and 36:11. (Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 120a.) According to the Gemara, Zelophehad's daughters demonstrated their righteousness in Numbers 36:10–11 by marrying men who were fitting for them. (Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 119b.)

Commandments[]

Moses Maimonides

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 2 positive and 4 negative commandments in the parshah:

- To give the Levites cities to inhabit and their surrounding fields (Numbers 35:2.)

- Not to kill the murderer before he stands trial (Numbers 35:12)

- The court must send the accidental murderer to a city of refuge (Numbers 35:25.)

- That a witness in a trial for a capital crime should not speak in judgment (Numbers 35:30.)

- Not to accept monetary restitution to atone for the murderer (Numbers 35:31.)

- Not to accept monetary restitution instead of being sent to a city of refuge (Numbers 35:32.)

(Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandments 183, 225; Negative Commandments 291, 292, 295, 296. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 1:196, 239; 2:271–72, 275–76. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:216–35. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.)

Haftarah[]

The haftarah for the parshah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Jeremiah 2:4–28 & 3:4.

- for Sephardi Jews: Jeremiah 2:4–28 & 4:1–2.

When parshah Masei is combined with parshah Matot, the haftarah is the haftarah for parshah Masei.

When the parshah coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (as it does in 2008), Isaiah 66:1 & 66:23 are added to the haftarah.

Further reading[]

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical[]

- Exodus 21:12–14.

- Numbers 27:1–11 (Zelophehad's daughters).

Philo

Early nonrabbinic[]

- Philo, Allegorical Interpretation 2:10:35; That the Worse Is Wont To Attack the Better 40:147; On the Unchangableness of God 37:183; On Drunkenness 30:114; On the Confusion of Tongues 13:55; On the Migration of Abraham 25:139; On the Change of Names 37:203; On Dreams, That They Are God-Sent 2:4:30; The Special Laws 1:32:158–61.] Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 41, 128, 173, 217, 239, 266, 358, 390, 548–49. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

Josephus

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:4:3, 7; 4:7:4–5. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 106–07, 114. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical rabbinic[]

- Mishnah: Shekalim 3:2; Sotah 5:3; Kiddushin 3:4; Bava Batra 8:1–8; Sanhedrin 1:6; Makkot 2:1–8. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Terumot 2:12; Challah 2:11; Bikkurim 1:2; Sotah 4:8, 5:13, 8:5; Bava Kamma 8:19; Bava Batra 7:1–18; Sanhedrin 3:7, 4:1; Makkot 2:1–3:10; Bekhorot 6:19; Keritot 4:3. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifre on Numbers 35:28. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 C.E.

Talmud

- Jerusalem Talmud: Sheviit 44a, 47b; Challah 15b, 18a, 44b–45a; Makkot 1a–. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 6b, 11. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006–2009.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 4b, 9a; Shabbat 33a; Eruvin 35b, 51a, 55b, 56b–57a; Pesachim 8b, 12a; Yoma 73a, 75b; Rosh Hashanah 2b–3a, 26a; Taanit 30b; Megillah 11a; Moed Katan 5a; Yevamot 6b, 13b; Ketubot 33b, 35a, 37b; Nedarim 81a, 87b; Sotah 27b, 34a, 47b, 48b; Gittin 8a; Kiddushin 42a; Bava Kamma 4a, 26a–b, 28a, 32b, 45a, 83b, 86b–87a, 91a; Bava Metzia 31b; Bava Batra 17a, 24b, 100b, 108a–39b, 159b; Sanhedrin 3b, 10a, 13b, 15b, 18a, 29a, 32a, 33b–34a, 35b, 45b, 49a, 53a, 69a, 72b, 76b, 77b, 84b, 91a; Makkot 2a, 5a–6a, 7a–13a; Shevuot 7b–8a, 33b; Avodah Zarah 9b; Horayot 11b; Zevachim 117a; Bekhorot 55a; Arakhin 33b; Temurah 16a; Keritot 26a. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Rashi

Medieval[]

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 33–36. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 4:403–34. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-029-3.

- Numbers Rabbah 23:1–14. 12th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Zohar 1:114a; 2:207a. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern[]

Hobbes

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, Review & Conclusion. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 724. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0140431950.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, 109, 111, 447. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- Bernard F. Batto. “Red Sea or Reed Sea? How the Mistake Was Made and What Yam Sûp Really Means.” Biblical Archaeology Review, 10:04. July/Aug. 1984.

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, 277–99, 497–512. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. ISBN 0-8276-0329-0.

- Mary Douglas. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers, 86, 103, 108–11, 113, 117, 120, 123, 125–26, 142, 147–48, 151–52, 161, 170, 183, 186, 229, 233, 235, 236–38, 242, 244, 246. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004. ISBN 0-19-924541-X.

- Jacob Milgrom. “Lex Talionis and the Rabbis: The Talmud reflects an uneasy rabbinic conscience toward the ancient law of talion, ‘eye for eye, tooth for tooth.’” Bible Review. 12 (2) (Apr. 1996).

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 21–36, 4A:509–79. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000. ISBN 0-385-41256-8.

- Joseph Telushkin. The Ten Commandments of Character: Essential Advice for Living an Honorable, Ethical, Honest Life, 275–78. New York: Bell Tower, 2003. ISBN 1-4000-4509-6.

External links[]

| |||||||||||||||||||